Few places in the world have the magic of Pátzcuaro. Surely the Purépecha Rey Curateme had to have known that back in 1324 when he founded the town.

For many visitors, Pátzcuaro spells the Island of Janitzio, the Basilica, the two main plazas, a library with the great Juan O’Gorman mural, picturesque red-and-white tile-roofed buildings, and the gateway to the arts and crafts of the lake. But it’s much, much more than that. Revealing itself and its history in small doses, little by little, every moment in Pátzcuaro is magic and serendipitous.

Too many people think of Pátzcuaro only as a venue for Semana Santa, Dia de los Muertos, or Christmas, and that’s a shame. Festivals dot Pátzcuaro’s calendar, but even ordinary days are special here. And it’s the ordinary ones that sometimes reveal the most of the town’s charming style and character.

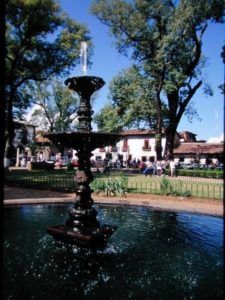

It’s Friday morning, and I’m admiring the Plaza Don Vasco from my favorite room at the Hotel Mansion Iturbe. Under the golden lights of dawn, the plaza shimmering amber after the nightly rain, the street sweepers are at work. I head for the market, just to watch the vendors arrange the day’s offerings of fresh fruit and vegetables. Then there’s the constant challenge of trying to get just the right light for the perfect photograph of the statues of Vasco de Quiroga and Gertrudis Bocanegra. This is a magic moment of quiet calm in Pátzcuaro.

The Café Doña Paca at the Mansion Iturbe opens at 8:30 a.m., greeting its patrons with its trademark tiny sugar cookie stars and steaming coffee. If there is breakfast in heaven, those cookies will be on the menu. The breakfast menu is a culinary tour of Mexico, offering up machaca Sonorense, enchiladas with mole Poblano, and chilaquiles in the style of the Tierra Caliente. A casual ambience pervades the air as guests exchange their plans for the days ahead.

Presiding over the Café Dona Paca is the visage of none other than Doña Paca herself (Francisca de Iturbe y Anciola), whose fifth-generation descendants Margarita Pedraza and Luis Pedraza own and operate the Mansion Iturbe with their mother, Margarita Arriaga. The painting dates from around 1840.

Francisco Castilleja happens by around ten, suggesting a trek over to San Francisco Uricho, a tiny burg on the way to Erongaricuaro and the home of the last Purépecha women still planting organic multi-colored corn and making corn tortillas to support their families while the menfolk work in the Otro Lado. Our favorite tour guide in the Lake Region, Castilleja is a veterinarian and philosopher who always adds insight to any journey.

But we need to shop. And we’re on a mission for something truly out of the ordinary today.

Now, the Bishop Vasco de Quiroga may have had more than shopping in mind when he came over here from Spain in 1532 to heal the ravages inflicted upon the peaceful locals by his countryman Nuño Beltrán de Guzmán. Thomas More’s Utopia had been on the best-seller list already for some sixteen years, and its impact surely wasn’t lost on the kindly bishop who ignored the mandates from his superiors and busied himself encouraging the indigenous folks to develop unique products to trade with one another, kicking off a 16th century building boom that assured Pátzcuaro’s place in the Tarascan culture of the times as well as in the Mexico of today.

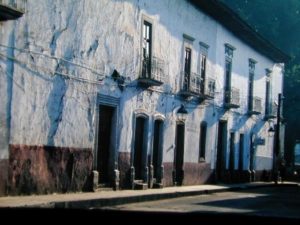

Consider Pátzcuaro’s main square – the Plaza Don Vasco. Actually, there are two plazas, but that’s not the point. Most Mexican towns have a church as the focal point, but not Pátzcuaro. Why? Pátzcuaro was built for commerce. The buildings which surrounded the plaza were meant for business, not worship. In the century that followed, Mexican sea trade with the Far East meant that wares had to travel from its Pacific ports inland. And Pátzcuaro was a waystation and customs house for those exotic goods destined for points far north. The old customs house, the ex-Real Aduana, is located on Calle Ponce de León, just off of the Plaza Don Vasco.

Back in those days, mule teams were the only means of transport. Someone had to provide an exchange of mules, provisions for the mule drivers, and all that an arduous overland voyage would require.

Pátzcuaro’s commercial focus didn’t interfere with the practice of the faith, and churches abound in this town. The most famous, of course, is the Basilica of Nuestra Señora de la Salud, which Vasco de Quiroga started to build around 1543. He had hopes that this would become a great cathedral, but the original plan – an edifice comprised of five naves, capable of holding about 30,000 people at a time – was quelled by the usual Church politics. Only one nave was ever completed, but it has just undergone a marvelous restoration. The Virgen de la Salud (Our Lady of Health), shaped in pasta de caña graces the main altar, and Vasco de Quiroga’s remains are located in a masoleum at its entrance. The churchyard is lined with milagro vendors, and no trip to the Basilica is the same without buying up at least a few. A little good luck and gratitude never hurts.

Across the street from the Basilica, at Calle Arciga 30, is Hilda and Raul Elizondo’s store, Galerias del Arcangel, a favorite for furniture, home furnishings and décor. We wander up to Av. Beningo Serrato No. 17, where for ages the Familia Dimas Molina has owned the Taller Artesanal de Velas y Veladoras Tata Ole, making and selling candles of every hue, scent and kind.

Pátzcuaro reveals its magic in the most unexpected places. From the Basilica, we cross the street over to the Museo de Artes Populares at the corner of Quiroga and Lerin. Formerly the old College of St. Nicholas (which was later relocated in Morelia), the building and its courtyard strikes as much interest as the exhibitions of regional handicrafts. Take a close look at the floor: cattle vertebrae punctuate floor tiles. The back yard holds some genuine surprises: a troje (a wooden cabin typical of the region) and the base of what once was a Purépecha ceremonial center.

Cross the street to the south, and enter the Ex Colegio Jesuita, a rambling behemoth of a building which has seen prior incarnations as the second college founded by the Jesuits in Mexico, a seminary, city hall, military barracks, and elementary school before its present use as a cultural center and Academy of Fine Arts. The walls of the huge upstairs rooms reveal an elementary school version of Cliff Notes, harking back to school days long past. The café is a restful and quiet oasis serving a variety of teas, salads, and sandwiches (and even Pop Tarts).

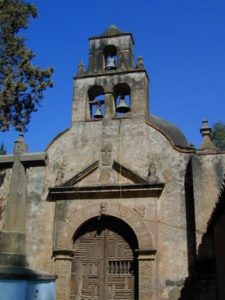

Walk down the hill, we stop at El Sagrario, the Church of the Shrine, where appearances can be deceptive. Although the somewhat modest and frankly crumbling building holds a genuine surprise inside for those who simply must have that Baroque-Churrigueresque fix.

From there we walk over to Casa de Once Patios (House of Eleven Patios), formerly a Dominican convent and before that, the Hospital of Santa Martha. Here is a delightful warren of one-stop shopping for everything in arts and crafts from Michoacán – chuspata figurines, tablecloths, rebozos, pottery, wooden chests and toys, Christmas wreaths, wrought iron, laquerwork, embroidery and lacy drawnwork. Craftmaking demonstrations are sometimes part of the show, but the even better one is channeling back into time and wondering how good life in a nunnery might’ve been. There are no longer eleven patios; only five remain. The hexagonal tiled bath gives some clue to the gracious style of life the convent’s inhabitants may have enjoyed.

You may need a pack mule to carry everything you buy at Once Patios.

Following the Casa de Once Patios down the hill, we reach Dr. Coss, a street which changes its name to Ahumada a few blocks away. Turn right, and the Plaza Don Vasco comes into sight.

A few steps away on Dr. Coss awaits our next stop – Diseño y Artesania – a gallery of casual clothing designed by Esperanza Sepulveda. From long dresses to jackets and pants, there’s always something to fit every shape; a silk shawl can make these togs go from poolside to elegant evenings. Dr. Jose Ma. Coss. No. 1-A. Tel/Fax (434) 342-2975. [email protected].

The Casa del Naranjo now beckons, and we wander into Artesanias Mojiganga, where Rocio Matamoros Martinez and Felipe Ortega Hernandez, who represent a cooperative of artisans, mostly potters, from distant parts of the state of Michoacán. Ortega’s knowledge of artisans and their techniques, such as Huáncito’s Elena Felipe Félix and Bernardina Rivera Baltazar, is simply unparalleled. We rate Artesanias Mojiganga the best place in all of Michoacán to find high-end examples of the hidden treasures of the Meseta Purépecha. Casa del Naranjo, planta baja. Plaza Vasco de Quiroga No. 29-2. Tel. (434)342-4695. [email protected]

We debate over whether to sip café and have a piece of carrot cake at La Escalera Chueca, a great “just looking over the plaza” sidewalk cafe or to head over for ice cream under the portales. The sticky wholesome goodness of nieve de pasta, which incidentally refers to an ice cream fortified with the heart of corn and not macaroni, draws us over to the Portal Hidalgo.

And afterward, my newest favorite store: La Casa Grande, at Portal Hidalgo 69, right at the corner of Calle Ibarra, stocked with high quality merchandise – decorative arts and household wares – from all over Michoacán. The gracious owner, Rocio Leal, a descendant of one of Pátzcuaro’s old-time leading families, knows her merchandise, and she knows how to price it fairly. From Estanzuela dinnerware, made in Tlapujahua off in the eastern end of the state, to lacy rebozos from Aranza in the Meseta Purépecha, there is something for every taste in this store. My favorite piece, the delicately polychrome blue Virgen de la Salud, no longer graces the wall. It’s gone, and I’m heartbroken. “We can get another one,” Sra. Leal offers, but sadly, I haven’t the money.

We round the block to the narrow Callejon de Don Vasco in the middle of the Portal Morelos. Slipping past a store selling incense and slippers, we find a small stall where the ladies of the Island of Janitzio sell hand-made embroidered aprons, beribboned blouses, and skirts, authentic versions of their own daily wear. The Callejon de Don Vasco is expanding into the back yard, and the small stalls bear exploration.

Now, there are stores selling exotica, arts and crafts, souvenirs, and works of art all over Pátzcuaro, and I’ve only named a few of my favorites. But none strike my heart like the old-time abarrotes and general stores whose names hint of glorious times past – stores like El Golfo de Mexico and El Cairo. My favorite – La Surtidora – located smack dab in the center of Portal Hidalgo, sells everything a person could ever want, from staples like chiles and beans to the ubiquitous Ramen soup, at least ten different kinds of rope, mouse traps and powdered Niagara starch, photocopies and hackamores, to soft candy and hard liquor. I cannot contain my wide-eyed enthusiasm for simply walking in and staring at the shelves, wondering what stories those rafters could tell of times past in this family-run, century-old mercantile. I try to encourage others to look at this marvelous piece of living history, meeting up with bored resistance most of the time. But today would be an exception.

La Surtidora had the very item we’d been looking for, one of those things that we didn’t even know we needed until we saw it – a galvanized tub.

“I’ve been looking all over for one of those,” exclaimed the Sister (who is really my sister and not a nun), revealing the emotions one usually saves for a sale at Saks. The size she wants – one big enough to feed a mule isn’t in stock. But now I know one thing she’s definitely getting for Christmas.

And she’s not getting a mule.

La Surtidora’s not the kind of store that will show up in the latest tour guide of great shopping places in Pátzcuaro, but it’s definitely a must-see on anyone’s tour of the town. If you don’t know what you’re looking for, you’ll always find it at La Surtidora. It’s as much a part of Pátzcuaro’s history – and its magic.

But there’s more to the story than just mules.

We are back at the Mansión Iturbe Casa de Comercio y Arriería, better known in these days as the Hotel Mansión Iturbe. To be accurate, we’re sitting at the Viejo Gaucho, the restaurant which adjoins it. Back in 1784, Francisco de Iturbe y Heriz, a native of Vizcaya, Spain, was sent to Pátzcuaro by his uncle, with orders to establish a “Casa de Arriera,” a service providing mules. Before long, he found himself married to Doña Josefa de Anciola del Solar y Perez Santoyo, and together they had five children. In time he became one of the most influential men in the community, thanks to the active trade between Acapulco, Morelia (which was called “Valladolid” back then), the Bajio and Mexico City.

One of Franciso de Iturbe’s daughters, Doña Francisca de Iturbe y Anciola, married Don Francisco de Arriaga y Peralta, a descendant of Don Antón de Arriaga, who came to Michoacan in 1524 to accept the land grant, the “Encomienda de Tlazazalca,” from the conquistador Hernan Cortez. And it was she who received the Mansion Iturbe as her dowry upon marriage.

The Mansion Iturbe witnessed the passage of many important events which impacted the country’s history. As the 19th century dawned, the mansion’s balconies saw Royal and Insurgent forces, as well as the conservatives and the liberals, pass through the town. One family member, Don Luis Arriaga Iturbe, thanks to his republican convictions, persuaded General Regules to rescind orders to burn Pátzcuaro on January 6, 1867. He went on to serve as mayor of Pátzcuaro from 1880 to 1909, and the next municipal government named the square next to the Basilica in his honor.

The years following the Revolution forced the descendants of Don Luis Arriaga Iturbe to abandon their residence in the mansion, leaving it in the hands of caretakers for a number of years. In 1970, Margarita Arriaga Pierres, barely in her twenties, embarked upon the ambitious and careful restoration of the mansion to give it renewed life as the Hotel Mansion Iturbe, a small historic inn now recognized as one of the Tesoros de Michoacán.

From mules to casual elegance? That’s the magic of Pátzcuaro.

WHERE TO STAY:

- Hotel Mansion Iturbe. A four-star family-run historic inn. Rates, $80 to $125 USD, depending upon the season. Special offers during low seasons.

- Portal Morelos #59. Tel. (434) 342-0368 and 342-3628. Fax (443) 313-4593.

- Hacienda Mariposas Resort & Spa. Rates, $100 to $200 USD.

- Carretera Patzcuaro-Santa Clara Km. 3. Tel (434)342-4728. USA and Canada: (800) 573-2386 [email protected] –

WHERE TO EAT:

- El Primo Piso. Plaza Vasco de Quiroga 29 (on the second floor of Casa del Naranjo). Hindu chicken, chicken with walnut sauce, pasta, salads, and glamorous dessert creations.

- Café Dona Paca. Portal Morelos 59. Regional specialties ranging from chirupo (a meaty stew) and corundas (sextahedronal tamales) to trout. And the best cappuccino around!

- El Viejo Guacho. Iturbe 10. Empanadas, steak, pizza, and excellent tossed salads. The Mansion Iturbe’s evening restaurant, featuring live music amid a South American theme.

- La Cocina de los Angeles. Av. Lazaro Cardenas No. 158. Authentically French. Cassoulet, escargot, daub de boeuf.

- Don Rafa. Benito Mendoza 30. Home-style Mexican food.

- La Escalera Chueca. Portal Guerrero 27. A sidewalk café.

TOUR GUIDE:

Francisco Castilleja (“Kiko”), who speaks Spanish, English and French, can be reached in Erongaricuaro at (434) 344-0167, or at the Mansion Iturbe at 10 a.m. daily except Sunday. [email protected]