A Balloon in Cactus

In 1916, an intrepid reporter, Guillermo Ojara, was assigned by his paper, El Demócrata, to go south to seek and interview Emiliano Zapata.

After harrowing incidents with hundreds of Zapatistas in the mountains, valleys, even The Hill of the Scorpions inhabited by thousands of those deadly creatures, Ojara was finally brought to his subject.

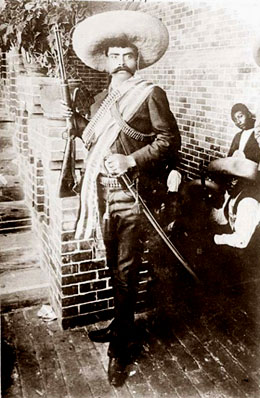

It is interesting to note that Zapata was called “El Attila del Sur” by his men, and frequently signed his public proclamations with that title. Without further delay, here, in part, are Ojara’s words, which tell us much about Zapata’s physical appearance, charismatic presence, and philosophy of justice for the poor.

“I advanced toward the hut. Entirely surrounding the little stone house were men, all dressed in black, all armed with rifles and revolvers, all evidently on guard. The entrance to the hut, a doorway, the stones of which were held up by uncut timbers from the hills, was closed by a blanket hung loosely from the top, beneath and around which light came. The guard rose as we approached and barred the way into the hut, but as we talked, the curtain was brushed aside and Zapata himself stood in the doorway.

“More than ever seeming the creature of ill omen which he has been to Mexico, the bandit leader, almost six feet in height and thin to the point of slenderness, stared out into the darkness, the blackness of his charro suit accentuated by the light which flowed around him.

“What do you want?” he asked

.My guard started to reply and Zapata broke in:

“I am talking to the stranger, not to you; speak when I speak to you. Go to your post.”

The guard left me, though I was still surrounded by the personal bodyguard of Zapata, who had risen from their positions around the hut and stood in a semi-circle back of me, as if to prevent flight.

“Now,” said Zapata, “come in here where I can see you. Too many people want to see me. What do you want?”

I presented first my letter from El Democrata, … and told him that I had been sent to secure an interview. About a dozen men lounged in their serapes on the dirt floor of the hut, while a rough table, containing several bottles of wine and cognac, stood in the centre. Zapata pretended to read the letters, though he can neither read nor write, and then, complaining that the light was poor, called a short, stout fellow, whom I afterward learned was Ismael Palafox, his “secretary,” to read them for him.

Apparently satisfied, Zapata offered me one of the bottles on the table, from which I took a drink of the fiery cognac de Madero, so well known throughout Mexico. Sweeping his hand around the room, Zapata invited me to sit down, and, dropping into the crosslegged seat of the Mexican Indian, proceeded to stare at me for fully five minutes, during which time I had ample opportunity to study him.

Dressed simply in a plain black suit, but with large diamonds on both hands, and a heavy gold watch chain running across his breast, his belt filled with cartridges and an automatic pistol slung at either hip, Zapata turned toward me the unexpressive face of an Indian of about 50 years of age, relieved by remarkably penetrating eyes. His head was small for his size, his face oval, and rather whiter than that of the average Guerrero Indian, thus betraying his share of Spanish blood, but his hands and feet were large, his mouth, under the heavy black moustache, loose and sensual, though the chin was firm, and the ears large but set close to the head.

“So you want to know why I fight, and how strong my forces are?” Zapata asked.

“Yes,” I replied. “Your career has attracted much attention in Mexico and in the world outside, and I have come a long way to tell all these people just what you want and how you expect to get it.”

“I am fighting for three things,” replied Zapata, when coffee was brought: “first, to free all Mexico of foreigners,, especially the Spaniards and the Americans; second, to give back to the Indians their lands, taken from them by the Diaz Government, the Madero Government, and now by the Carranza Government; third, to give Mexico an honest President, a ruler who will give justice to the 14,000,000 poor people as to the 2,000,000 so-called upper classes and the few hundred thousands of foreigners who have been allowed to drain the country of the great riches of the soil. I have fought for these things for nearly six years, and in the territory under my control every foreigner has been driven out or killed; every wealthy Mexican has been compelled to return his wealth to the Indians, to whom it rightfully belongs, and the land has been distributed to every peon who wanted a share of it.

“I am the man who should be President,” Zapata continued. “Diaz, de la Barra, Huerta, Carranza, and Villa have tried to rule the country, along with half a dozen others, and all have failed. When I was in control in Mexico City I maintained better and more honest government than any of them. Thus I have proved that I am best fitted to rule the country.”

“Do you plan to seize the Presidency?” I asked.

“That is something I do not care to disclose,” Zapata answered.

“But if you become President what do you plan to do?” I persisted.

“The first thing will be to drive all the foreigners from Mexico. All of them have done Mexico much harm but the first ones to go will be the Americans. Then I will destroy all the railroads, so that they cannot come back. Before we had railroads we had few foreigners, especially few Americans, in Mexico and we were happy. If we had no railroads now we should have no foreigners, and we should have peace and happiness again. Mexico can produce everything she needs; therefore we do not need any foreign trade. Outside commerce always has been for the profit of the foreigners and not to the gain of us Mexicans, so why should we allow it?”

“But what if the foreigners, especially the Americans, should demand that you open your ports to their trade, as they once did to the Government of Japan?” I asked.

“When?” Zapata questioned, and, without waiting for a reply, went on:

“The United States could not compel the great Japan to do anything. Once the United States invaded Mexico, and I have heard that the Mexicans of that day drove them out with fearful slaughter. What we did once we can do again, and if the Americans come into Mexico we will drive them clear beyond Texas, and maybe take that away from them.”

It seems impossible that any man of the age of Emiliano Zapata should entertain such ideas, yet, he spoke with the utmost sincerity and with a note in his voice that left the hearer sure that he, at least, believed fully in what he said.

“I have nearly 25,000 men,” he continued, “and each one of them believes as I do — that we are the men to govern Mexico. Every one of the rulers Mexico has had has sent an army against us and we have defeated all of them. They sent good armies, as good as those of the United States; if we defeated them, why should we not defeat those of the northern republic We have killed many Americans, and nothing has been said about it, so the Americans must realize that we are all-powerful, and when we want to kill we kill, being responsible only to ourselves.”

“Then, if the United States sends troops into Mexico, you and your army will fight them?” I asked.

“Certainly, we have voted on it, and every one of all my army is in favor of fighting for Mexico against any one who tries to interfere in our affairs. When the United States landed troops in Vera Cruz, and the coward Huerta refused to fight, did I not send my men down to the outskirts of the town of Vera Cruz? Why did I send them? To look at the American troops? To see the disgrace of the Mexican flag?” Zapata got up, and walked across the room, shoving his men out of his way with his foot as they slept on the floor.

“No! I sent them to fight the invaders, if Huerta had shown the bravery of a mole.

But I could not fight them alone; they were too many for me, and I could not spare more of my troops from Morels and Guerrero, where we had to stand guard to keep Huerta and his army from robbing the poor people again.

“But, if the United States comes into Mexico again, I shall call every Mexican to me, and every loyal man will come. I have found it easy to gather and maintain an army against the usurpers of power in Mexico City, so shall I find it easy to gather twice as large an army to give battle to a foreigner who is trying to seize our country.”

Zapata discusses with Ojara how he obtains food and ammunition for his men, how they use it, and about crimes he and his brother, Eufemio, committed in the Southern States. Here we pick up more of Ojara’s observations on the legendary General Zapata:

“As dawn came, he politely excused himself, rolled in his serape on the dirty floor and fell immediately asleep. I followed his example and it was nearly noon before I awoke. There was no one in the cabin, and when I looked out, only a group of about 50 men remained of all the Death Legion which had been on guard the night before. Zapata was nowhere in sight.

I was informed by the leader… that “Attila has gone, but has left word that we are to follow him. … It is General Zapata’s wish that you accompany him,” was all the answer I could get.”

Ojara has no choice but to follow and connects with General Zapata four days later “riding his huge black horse and directing the attack of nearly 5,000 men on the cuartel in Coyoacan” with dynamite blowing the roof off the barracks and Carranza soldiers covering their retreat with the fire from two machine guns, fleeing into the plaza of Coyoacan “where a number of street cars on the suburban lines from Mexico City had been stopped. After all available street cars had been filled and gone, machine gun operators drew their automatic pistols and fought until they were overwhelmed by a charge of the Zapatistas…. After some weeks the watch on me relaxed a little, as Zapata appeared to have some important business with outside agents who were constantly sending him couriers, and I finally escaped early one morning, and by hard riding reached Mexico City March 2. I abandoned my horse and saddle at Xochimilco, and, catching an interurban electric car, rode into the capital.”

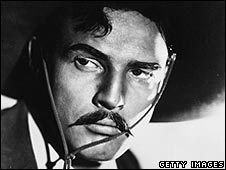

Zapata was such a powerful figure in Mexico, that it seems fitting an actor with the power of Marlon Brando play him in the movie, “Viva Zapata!,” written by John Steinbeck, directed by Elia Kazan, with Anthony Quinn as Eufemio Zapata. How close did these great artists come to the real thing?

The 1916 interview above supports the film, and supplies additional facts: The real Zapata commanded vast sums of money from those in power, as much as $1,500,000 pesos every ten days, although, as he said himself, “The poor people bring me food, the Indians give me men and horses, and I have taken much money from the rich whom I have killed or driven from the country.”

Brando’s Zapata rode a white stallion, while the real Zapata rode a “huge black horse.” Brando’s Zapata married Howard Hughes’ wife, Jean Peters, while the real Zapata “talked of his triumphs with women, largely made by force of arms….”

I like to think the real Emiliano Zapata would be pleased with the resemblance between himself and Brando. He may not have liked the studio’s original choice for the part, Tyrone Power.