Good Reading

Lancandon Journal — 1969

Lancandon Journal — 1969

By Dimitar Krustev

Editorial Mazatlan, 2013

Note: While the cover says “Lancandón,” the legal page (and usual spelling) is Lacandón, used throughout this review.

Like most travel journals, Dimitar Krustev’s Lacandon Journal — 1969 lacks literary “finish.” Plebian in style it often just plods along; but, nevertheless, parts of it are certainly pleasurable. As in the unpolished letters we may have received in the past from some adventure-minded spirit, in this journal there are enough insights, observations, descriptions, and surprises to keep us fascinated.

For me, because I have some interest in the disappearing cultures (and disappearing wildernesses) of the world, and particularly those here in Mexico where I live, Lacandon Journal — 1969 turned out to be just the right book to read this early summer afternoon as I lay in my Maya hammock, one bare foot on the ground rocking me slowly back and forth, a gin and tonic with fresh mint, slightly crushed, on the sturdy rústico table beside me. At age 71, with some significant adventures of my own behind me, I realize, at least in my moods of late, how wise Emily Dickinson was when she wrote, “There is no frigate like a book.”

In July of 1969, Bulgarian born artist-adventurer Dimitar Krustev, almost 50 years old, and his inexperienced young companion named Gary set off, in their folding kayak, to explore, traveling on its waters, the jungles of southern Chiapas, the still largely unknown land of the Lacandon Maya. In 1969, this culture was already in decline, undermined by the relentless forces of what some still call progress. Editor Richard Grabman (whose fine book Gods, Gachupines and Gringos I reviewed in MexConnect a while back) writes in his Introduction that “The protestant missions, he [Krustev] more than hints, are not so much out to save souls as to exploit the Lacandón and Lacandónia for the benefit of outside economic interests.”

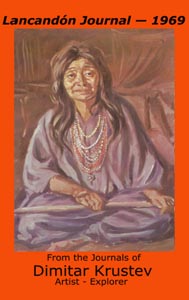

A month later, at the end of the journey recorded in this journal, Krustev says this about Kin Yuk, a Lacandón Maya whom Krustev had known for several years — who had tried civilization, living and studying in San Cristóbal but who had returned to the Selva Lacandona jungle — “He was a gentleman who made us feel like savages.” Throughout the journal, Krustev holds in high esteem those who live in the Lacandón (and who also are the subjects of his paintings, one of which graces the cover… perhaps someone will someday publish a collection of his paintings).

To Krustev, the relations between family members seemed “almost utopian.” He is compelled to make notes like these: “Parents showed great love and affection toward their children, who rarely disobeyed their parents.” “Husbands were attentive when their wives became sick, staying in the hut instead of working in the fields.”

Jungle adventures are always challenging. This trip was a very difficult one for Gary, his young companion, and although difficult as well for Krustev, the artist was generally of a calm and philosophically disposed spirit.

In one passage, Gary was “in agony, naked and being eaten alive by the rhododores [a biting insect related to the bedbug] while waiting for someone to show him the way out of the brush…. His back was covered with thousands of little spots, the bites of the rhododores.” Then the following evening to avoid “the torment of cockroaches” they slept in the tent, which proved to be a mistake “because it rained all night and saturated the old floor of the tent and everything in it, including us.” And then, as if that wasn’t sufficient torture, “tiny flies called chaquistes [jejenes or no-see-ums] entered the tent through the net and bit us all night.”

Part of every observant traveler’s journal are details of everyday life. Krustev records that for the protein portion of their diet, the natives used “the jungle as their ‘supermarket,'” which provided them with deer, monkey, toucan, wild turkey, wild boar, fish. But their main course always “included maíz — corn — as is common in Latin America.” And “I found a wide range of gourds, pumpkins, melons, onions, small tomatoes, bananas and beans all a part of their diet also.”

Although snakes were a worry and the heat and the humidity horrible (sometimes 110 degrees with 100 percent humidity), throughout the journey “Our great enemies were not the snakes or the heat and humidity. Our greatest enemy were the bugs. There seemed to be hundreds of varieties of them and they tormented me day and night.”

Midway through the journey Krustev reflects that “A man or woman who lacks a definite purpose does not belong in the jungle. Only an artist, writer, archaeologist or botanist could endure the jungle for a long period of time.” The heat, the humidity, the insects combine to make a man sluggish, “leading to depression and homicidal or suicidal thoughts,” a malady called “Jungle Madness.”

Although snakes did not become a problem, one entry is exclusively about them. There are 80 different kinds of snakes that slither through the jungles of Central America, 22 of which can kill a person. He even discusses in some detail “12 important and very dangerous snakes,” like the Nauyaka, which reaches a length of about five meters and can be unusually thick, from six to seven inches.” The really huge snakes are harmless to humans: the boa constrictor can reach 20 feet, the python 30 feet.

Gary, the young companion “who had never been in the jungle before,” steadily succumbs toward Jungle Madness. The experience with Gary reminds Krustev of his first companion on a jungle trip, “a woman, aged 35, she nearly shot herself in despair.” His second was a student, age 22, “who left at the first opportunity.” His third, aged 30, “was a jet pilot who stayed a week then took a plane that was delivering groceries at Bonampak.” Toward the end Gary could no longer carry his own bags, and so Kin Yuk, the Mayan, took up the load, “a load twice the weight of mine, and I couldn’t help but admire his endurance, strength and presence of mind.”

Surrounded by water, most of it muddy and teeming with bacteria, even Krustev begins to be affected: “I began to hallucinate about beer, Coca Cola and the crystal clear brooks.”

The epilogue is also illuminating, and it begins, “I want to end with a few words about my two companions. One was a perfect example of what the jungle can do to a novice; the other, Kin Yuk, was a perfect example of a superb guide, a true child of the forest, the last of the noble Lacandón.”

For me, reading these journal entries are actually better than “being there.”