Good Reading

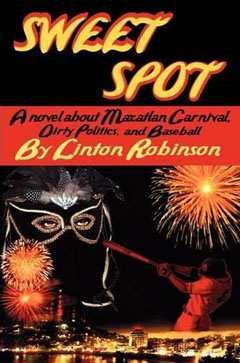

Sweet Spot: A novel about Mazatlan Carnival, Dirty Politics, and Baseball

A Mexico book by Linton Robinson

Adoro Books, 2009

Adoro Books, 2009

Available from Amazon Books: Paperback

The back cover of Sweet Spot tells us that author “Linton Robinson was a journalist in Mazatlán and other Mexico cities for years. And played a little ball in his time.” His protagonist and narrator — Raymundo Carrasco — likewise was a journalist in Mexico for years. And played a little ball in his time, including for the big boys up north.

Sweet Spot is set during seven spectacular days of Carnival in Mazatlán, the second largest Carnival in the world. A lot happens during those seven days, including scandal, murder, amoral politics, drug lords searching for our protagonist “Mundo,” and bed time with a desirable young revolutionary, the amoral Mijares.

Yes Mundo Carassco had played baseball for the majors, but he longed for Mexico and Mazatlán more than money and a potentially big career. Mazatlán was his home and Mundo loved playing for the home leagues. At Carnival time, Mundo has left his job as a popular local (largely political) columnist and is working in the Public Information Office at City Hall, defending the newly elected non-PRI (opposition party) mayor, Varedas, a stupid and violent man who has just been accused of beating his wife — a woman loved by the masses. Mundo took the job at City Hall because he wanted to be close to his passion, She of the Perfect Flesh, Mijares, head of the Public Information Office.

The Public Information office goes well with the general air of neglect and underfunding. Compared to publicity offices at the Arizona State University, for instance, it’s a dirty broom closet that could use a hose-down and exterminator. They’ve got us on the second floor, rear corner, diagonal across from the Mayor’s office. I take comfort from being as far as I can from the scene of inaction.

On the other hand, Mundo loves his late afternoons and his few (very few) luxuries in his ocean-view apartment:

The kitchen is one of those square cement scullery sinks Grady calls Mexican Maytags, a little refrigerator, and a propane tank powering a two burner stove that regularly tries to kill me. The bath is an open stall with a toilet and showerhead. Since I am at the same level as the cisterns that give any semblance of water pressure, I can only shower by turning on the pump that fills the cistern. I get a slightly pulsing shower, and only when the electricity is functioning. The bed is a concrete platform with a mattress on it and the table and chairs are white plastic with Pacifico beer logos — Toma Pacífico, ¡Nada Mas! The closet is a rod between the bath stall and the rear wall. I keep my clothes in an old ice chest, and books piled up on the refrigerator. Mi casa es su casa.

It’s very cheap. It’s also the greatest place I ever lived and I hope I never leave.”

It is his lady love, light of his loins, Mijares, his supervisor, who must cover for their boss, the brutal mayor, in the aftermath of punching out his wife, worshipped by the masses, Blanquita. On Mazatlán television Mijares masterfully re-directs attention from the scandal to herself, and soon she has the public “eating out of her cleavage.”

She shimmered with media cool, like a slab of dry ice on a hot sidewalk. Every color of her outfit — apparently stored in her desk or car with ‘Break Out In Case of Emergency’ stenciled on it — was perfect for pickup, as if dyed to match TV phosphors. Her makeup was a little too much for live viewing, but on camera turned her into the Goddess of Truth and Innocence. I even noticed a dark streak between her already pronounced breasts, giving them an even more emphatic enunciation. Dangling, stripy earrings framed her eyes in a parenthesis of moiré buzz. She sizzled liked a blank white screen, was as bottomless as dark glass. She had their number, but good.

Each chapter begins with a fitting excerpt from one of Mundo’s earlier columns or articles. The chapter I just quoted from begins, for example, with this piece about freedom of the press:

What you don’t hear as much, though it may be more important, is that democracy also requires a press that is intelligent, professional, and open. Governments don’t have to work very hard to censor a press incapable of uncovering facts or presenting them properly. “The New, Improved Corruption” by Mundo Carrasco Proceso, May 1999

Mundo’s chief advisor is his father, “very obviously Tarahuamara tribal stock.” He usually drops in on him at the athletic club after work:

He doesn’t get old, doesn’t erode, just gets sort of burnished. The Indian facial bones move up underneath the skin, his hair gets glossier, his eyes get more bottomless. I suppose a lot of people study their parents for clues to where they came from… or more important, where they’re going to end up.

His father had seen Mijares on television that morning, and he worries that Mundo is obsessed with her. His advice to his son: “Think about prayer, conejo. And condoms.”

Playing for the majors had given Mundo “the best seat at the full banquet of life,” but even then he was already writing, fascinated by politics, sports, sex: “I sold articles on the politics of the Caribbean Series and the impressions of a young Mexican hitting the major leaguers, which ran in Sports Illustrated, who wouldn’t have bought a cup of coffee from me if I hadn’t been a jock.” He knew in his heart what he really wanted was to return to Mazatlán, be a journalist, and play some ball:

I was scouted a bit for the majors but was homesick for Mexico and showing another trait that turned out to be life-long, a lack of big league vision. So I signed with the Mazatlán Venados. Small-timer syndrome you might say. But you know, I didn’t want to play in Fresno or Durham, I’d wanted to play for the Venados since I was a kid sitting in their bleacher section with my dad. I didn’t dream of hitting in Candlestick or Fenway or The Bronx, I always fantasized playing here in Venados Stadium.

For Mundo, “Being a big fish in a small pond suits me just fine.” That small pond could be dangerous, though, filled with hungry sharks who were hunting him down as he pursued a murder investigation. At one point he defends himself against real bullets with only his Louisville Slugger.

Even though he had been a reporter, Mundo in many ways is apolitical (perhaps what all reporters should be), observing more than committing as he moves through the complicated and dangerous world of Mazatlán politics and national politics, often offering intriguing and unexpected insights. In 2000 the PRI lost their seven-decades hold on the national Presidency, losing to PAN and their Coca-Cola candidate, Vicente Fox. Mundo tells us:

In the year since the PRI was voted out of the presidency, I had felt a loss. There was no longer an evil force to be struggled against, nothing to boot up my indignation and crusader complex. From now on the corruption will come from us, ourselves.

The PAN party is very conservative, very Catholic: “Before Fox, people said that the highest official of the PAN was the Virgin of Guadalupe.” Mundo believes that PAN is:

…the only party that doesn’t try to act like they care about the People, the Poor and the Helpless. They are unabashedly conservative and Catholic. All these leftist revolutionary parties posture and preen while the poor get poorer, acting out adolescent rebellion while quietly manipulating their scams — and here’s one party that wants to be Mom, wants to make us be responsible and go to church and clean up our rooms.

In a dormitory of leftist students, Mundo peers into “filthy communal bathrooms, chill out nooks plastered with layers of music and political posters…. You could peel them off and trace some sort of history of superficial political thought. The constants would be Che and Jim Morrison.”

And the “Zapatista types”?

It’s one of those obvious but carefully guarded truths that the Zapala ‘army’, the EZLN, is not really the spontaneous white pajama-ed peasant uprising that it suits everybody to believe it is. And it’s fashionable to see the strike that paralyzed the Universad Nacional Autonomo de Mexico for a year as a student expression.

Actually both of them were cold-blooded political manipulations by entrenched leftist groups, power plays that blooded everybody involved except the rich men and pampered kids who instigated them.

Sweet Spot overflows with baseball, politics, sex, and even love. Mundo’s obsession (obsession is the curse of the romantic) is, of course, the scorching Mijares:

She’s a broken power line swinging around in the wind, striking showers of sparks off the cars and buildings…. She’s that few seconds between losing control of your car and slamming into something solid. I don’t need her at all, but of course I have no choice but to moved towards her; my mouth and eyes and veins and nostrils blown open, my hairs standing erect, my breath oppressed, my heart bailing out, my brain choked down to a dull reptile throb. Love is a disease. She’s the only known cure.

When Mijares pats his lower thigh under the table, it has “the same effect as plugging it into a wall socket.”

But in those moments when Mundo is not obsessed with Mijares, or fleeing for his life, he is able to make thoughtful comments about the United States and Mexico. He thinks that the American press makes too much of what, after all, is life in all its corruption in both America and Mexico:

In the American movies there’s a formula, some dark secret or shocking revelation… buried so deep it takes two hours and a car chase to figure it out.” “But in Mexico, what would that dark secret be? Drugs? Racketeering? What’s the big secret? Especially in Sinaloa, the major marijuana and heroin producing area in the hemisphere. A Sinaloa politician not being involved with drugs would be like a Texas politician not involved with oil or cattle. Americans play shocked and virginal over this, even though it was the U.S. that originally started opiate cultivation in Sinaloa and provides the market and laws that support the industry.

Tired, terrified, his girl in the arms of another (various anothers), Mundo teases us for a moment into thinking he might escape back into his heritage, “the Indian world of old Mexico. To take magical measures to deal with reality.”

But then, just as we are thinking he might be serious, Mundo looks at us directly and says: “Just kidding. Though I suspect you wanted it to go that way, get back to my Native roots. Eat peyote and go to some brujo for a vision. Sorry, but Mexico is a modern country, at least the Mexico I live in. The ‘real Mexico’ isn’t peasants with burros and tribes with funny hats….”

Our hero lives in the real Mexico, and he loves it just the way it is, as well as its traditions: “I like old Mexican songs the same way I like coffee. Dark, creamy, overly sweet, served by pretty women, spiked with fine tequila.”

Sweet Spot is incredible. Linton Robinson should be catapulted to the top of the pile of contemporary authors. Why didn’t this novel win the National Book Award or the Pulitzer Prize?

Like Twain’s Huckleberry Finn, Mundo is an innocent. Trying to survive in a world that presses too much upon him, Mundo offers a dazzling wit that is endearing because the hero does not himself realize it is so dazzling, and he offers perspectives on a complex and perplexed society that, paradoxically, most clearly can be seen only by an innocent.

I’ve read a lot of novels in the first ten years of this new century, and I must say that Sweet Spot is one of the three or four I like the best.

The press release to promote the novel announces that Linton Robinson’s “work is very much affected by the decades he has lived in various parts of Mexico and Central America. “Sweet Spot” is a valentine to the eight years he lived on a hill right above the throbbing heart of Mazatlán’s carnival celebration, wrote for local newspapers, and hung out with the local musicians, athletes, and criminals.”

And what have I left out? Oh yes, “based on a true story.”