“My father thought Mexico was the best place on earth,” said Isabel as she heaved a huge pot for steaming tamales onto the stove in her kitchen. “But he always felt like a Spaniard. Always like an adopted son. And even though he loved it here, he sometimes generalized about how ignorant or backwards the Mexicans were. This attitude drove my mother crazy because she was a mountain girl who knew the enormous dignity of the country people. In that way he was always a conqueror.”

It was the full moon in August and we were talking again about Isabel’s father. Since she’d received her father’s family portrait from her cousin Martin in Spain, it was all we could do not to talk about it. The portrait now hung framed in her kitchen just above the counter where we worked. This morning we’d begun serious preparations for a gathering that was to be held in Isabel’s garden. A Huichol shaman, a maracame en route from Santa Catarina in Nayarit, was conducting a ceremony for thirty people this evening. As hosts, the task to keep thirty people warm was going to be tough. Three days earlier the weather had turned unseasonably cool and in between conversations about Alberto Fuente we fretted about the amount of hot food and drink we’d need to serve.

“When will the maracame begin chanting?”

“At moonrise. And he’ll continue until dawn.”

“When will we ingest the peyote?” I asked, trying to get a sense how the night might proceed.

” Quizá once.” Maybe 11.

We’d been shopping all morning for supplies and the kitchen was heaped with food. There were three kinds of tamales and the makings for three kinds of salsas, boxes of chocolate discs wrapped in waxed paper for the bottomless pots of hot chocolate we were going to serve, mountains of fresh chamomile, and most importantly, fifteen small peyote cacti, gathered from the mountains of San Luis Potosí and delivered yesterday to Isabel’s door. These were to be washed, carefully trimmed of their strychnine tufts, and then sometime after midnight, dropped into a blender, mixed with passion fruit juice and served in tiny glasses to the people participating in the ceremony. This was not my first experience with peyote, but it was my first experience in a circle with a Huichol maracame where only one other person spoke English.

We’d been shopping all morning for supplies and the kitchen was heaped with food. There were three kinds of tamales and the makings for three kinds of salsas, boxes of chocolate discs wrapped in waxed paper for the bottomless pots of hot chocolate we were going to serve, mountains of fresh chamomile, and most importantly, fifteen small peyote cacti, gathered from the mountains of San Luis Potosí and delivered yesterday to Isabel’s door. These were to be washed, carefully trimmed of their strychnine tufts, and then sometime after midnight, dropped into a blender, mixed with passion fruit juice and served in tiny glasses to the people participating in the ceremony. This was not my first experience with peyote, but it was my first experience in a circle with a Huichol maracame where only one other person spoke English.

With Beto’s help we’d already cleared a huge ring in the garden, dug a fire pit, and stacked a load of firewood and ocoté near the chair the maracame would use. We’d gathered passion fruit, the maracuyá, that had fallen from the vines. As we stacked the fruit in a stout tulé basket, Isabel told me that the best specimens were yellow, the slightly withered ones that looked past their prime. “They give the best juice,” she advised, and they did when scooped, blended with water and sugar and strained. “Sometimes in the sun I can smell the juice’s perfume coming through my skin,” she’d said, not knowing how utterly exotic that had sounded to me.

By 8 p.m. we sat in the kitchen, waiting for guests to arrive, with glasses of tequila in our hands. The maracame, Eusebio, had arrived at 5:30, dusty and tired from a long bus trip. He was lying on the bed in Isabel’s guest room with his eyes closed and his hands folded on his chest. I’d been setting up a table for offerings on the terrace when he’d pulled the string on the bell outside the garden door. He’d called out “Eusebio” when I asked who he was. When I opened the door I met a big-chested man with glossy brown skin wearing the embroidered white manta cloth tunic and pants of the Huichol. His voice was pleasant and his eyes calm as we exchanged greetings. He was alone and carried a woven shoulder bag.

As we sat waiting for the night to begin we returned to our favorite topic, Isabel’s father. Isabel walked over, slipped the portrait from its nail and placed the picture on the table between us. As the tequila worked its way into my bloodstream I stared at the sepia eight-by-ten photograph of the Fuente family. Six handsome people looked out at me from the past. Alberto Fuente sat in the middle of the photo looking like he wanted to be somewhere else. For a boy of thirteen, posing for a family portrait must have driven him crazy. Behind him to his left sat his mother Isabel, a widow. Her husband, Estanislao, had died from a heart attack seven years earlier. Her face, composed and pleasant, hid the turmoil of the years following his death. As the surviving parent, she owned the family home but faced the problem of how to earn enough money to meet the expenses of the family. Next to her, stood her oldest daughter, Isabel, named for herself in the same way men pass their Christian names onto their oldest sons. Isabel, the daughter, inherited the task of becoming the breadwinner for the family. Her marriage to Herminio Peréz became the wellspring for the family’s prosperity when she and Herminio began the department store, Casa Herminio. Because of her position in the family and her drive, the power in the family shifted from the mother to the daughter and she became the authority for the rest of the siblings. It was she who arbitrated disputes, handed out punishment, and chose the role each child would play within the family. Her face, well proportioned and strong, might have been sensuous had she not been imbued with so much authority so early.

As we sat waiting for the night to begin we returned to our favorite topic, Isabel’s father. Isabel walked over, slipped the portrait from its nail and placed the picture on the table between us. As the tequila worked its way into my bloodstream I stared at the sepia eight-by-ten photograph of the Fuente family. Six handsome people looked out at me from the past. Alberto Fuente sat in the middle of the photo looking like he wanted to be somewhere else. For a boy of thirteen, posing for a family portrait must have driven him crazy. Behind him to his left sat his mother Isabel, a widow. Her husband, Estanislao, had died from a heart attack seven years earlier. Her face, composed and pleasant, hid the turmoil of the years following his death. As the surviving parent, she owned the family home but faced the problem of how to earn enough money to meet the expenses of the family. Next to her, stood her oldest daughter, Isabel, named for herself in the same way men pass their Christian names onto their oldest sons. Isabel, the daughter, inherited the task of becoming the breadwinner for the family. Her marriage to Herminio Peréz became the wellspring for the family’s prosperity when she and Herminio began the department store, Casa Herminio. Because of her position in the family and her drive, the power in the family shifted from the mother to the daughter and she became the authority for the rest of the siblings. It was she who arbitrated disputes, handed out punishment, and chose the role each child would play within the family. Her face, well proportioned and strong, might have been sensuous had she not been imbued with so much authority so early.

Standing next to Isabel was Maria Theresa. A reserved girl with light green eyes, a small build and wearing a light fringe of bangs, she looked at the camera with a directness not seen on the other faces in the photo. At 15, just months after she posed with her family she went to live in a nunnery fifty miles south of Aviles. She lived as a nun for 18 years until she died in 1931. Just after her thirty-third birthday in April of that year, she felt a sharp pain from a molar in her jaw. For seven weeks she bathed the tooth with clove oil to stem the ache that gradually became torture. When the pain had become too intense to bear, she’d begged for zinc oxide to mix with the oil. With it, she formed a paste that she packed inside the cavity of the tooth. After four more excruciating weeks of agony she begged the Mother Superior to call a dentist to extract the tooth, but Mother Edwinia refused.

On a cloudless night in the middle of June the infection finally reached her heart as she lay writhing and sweating in the hard bed of her cell. It was Isabel’s likeness to this sister’s photograph that caused Martin to react so strongly to their meeting. Seeing Isabel was for him a clarion call from the dead. Maria Theresa’s death had created a deep fracture within the family. Half of them blamed the cruel Mother Superior and the other half had been either too young or too naïve to know that the death was senseless. Martin’s mother had sided with the part of the family who knew Maria Theresa’s death had been a crime. From the day he’d been able to understand their talk, Martin had heard bitter stories of her untimely death and watched as the edges of her photograph curled with age in its place on the family altar.

“Well,” I said, “that explains the mystery of meeting Martin, doesn’t it?”

” Sí. The past is a powerful thing, no matter how much we think we are free from it,” she said. And I agreed with her and for a while we sat sipping our tequila, thinking our own thoughts, and listening to the small sounds of the house.

At 10:30 p.m. the garden was filled with people sitting crosslegged on blankets around the fire. Eusebio had begun chanting around 10 and people sat quietly bundled in sweaters, scarves and gloves with their heads down and their eyes closed. The only light in the garden was from the fire and from the moon overhead. His monotonous chant, “uhn nun nun na, uhn nun nun na” had lulled most of us into a watchful trance, but for me the hour had stretched too long. I was uncomfortable sitting on the ground and I thought more than once that I wouldn’t last the night. After an hour of chanting he stopped to rest his voice, and I gratefully left the circle. Other people rose from their places to stretch, use the bathroom inside, or wander into the kitchen for cups of tea. The temperature had been steadily dropping and several people lit the fire we’d laid in the living room fireplace.

Isabel and several friends were already in the kitchen preparing the peyote drink when I got there. I busied myself with the tray and glasses and waited for them to finish while I clenched and unclenched my hands. My fingers were stiff from the cold. Finally the correct proportion of juice to cacti had been calculated and Isabel began pouring the concoction into the glasses on the tray. The maracuyá nectar was a pale yellow as it washed into each of the thirty glasses. One of the men offered to carry the tray outside so Isabel and I each took a glass, touched them together with the traditional toast of Salud!, locked eyes for a moment and drank. As we waited for people to be served their drinks, I asked her how her father had come to Mexico.

“Only four years after this portrait,” she said, tapping the picture on the table with her finger, “he bought passage on a ship to Cuba. He was only seventeen, but he’d been educated by the Jesuits and could read and write Latin well. A week before that he’d graduated with a Bachillero in Accounting. Right after the graduation he told his mother and his sister Isabel that he could not become a priest and that he was going to Cuba. They were so upset! He made all kinds of promises to appease them. He told them he’d only be gone a year and that he’d think about going into the church when he returned. But he couldn’t do it. When he was old and living on his own in Melaque, he used to tell us about it.”

“Ay, no. No, no, no, no,” he’d begin after drinks had been poured and he’d settled into his favorite chair on the terrace of his home in Melaque. “I was so stupid. I believed everything the priests told me about sin and celibacy. Even at seventeen I knew I couldn’t go through life without knowing the pleasures of women. Even before I knew a woman’s love, I watched how they moved and spoke. I smelled their hair and stared at their lips. I threw coins on the ground so I could crouch down and glimpse their ankles. But now I know how priests really are. I probably could have been a Bishop, you know, a Bishop, with an incredible woman in the kitchen.” He’d always pause and lower his voice before going on. “At seventeen, I knew I’d love fucking too much. And I did.”

“We always laughed so hard when he said that,” Isabel remembered with a smile on her face.

At two a.m., Isabel and I were in the kitchen arranging platters of freshly steamed tamales and stirring a huge pot of hot chocolate. It had been three hours since we’d tossed back our peyote and maracuyá nectar. We’d sat outside in the ring listening to Eusebio chant on and on into the night. He had ingested his own portion of peyote earlier in the evening and his experience of time had skittered into the air. He’d not rested for several hours and showed no signs of weariness. Isabel and I had quietly left the circle and made our way to the kitchen to prepare food. The peyote had begun to affect us and the minute we began whispering in the unsacred area of the terrace we abandoned English altogether. The drug had pushed open some door in my brain and taken me into the room labeled, “Spanish Only.” My ability to understand and speak it was absolute and effortless. I acknowledged the transition with a long moment of soaring elation and then reached out for one of the posts on the terrace. A moment of turbulence threw me slightly off kilter as the orbit of my world skipped another groove and moved closer to hers. We moved through the living room and into the kitchen, shucking our mittens as we set to work. As we transferred more tamales to the steamer, neither of us could leave the subject of her father alone.

“In Cuba,” Isabel went on, “My father met with his older brother Joaquin. Twelve years older than him, Joaquin had been in Havana since 1901. He was in the fiber trade with their father’s brother Hernán.” Cuba was a heady release from the formal world of Aviles, she said, and Alberto was finally given his chance to learn about love in the arms of a Cuban woman, who taught him danzón, how to lie naked in the sun, and to drink rum like a man. “He always remembered ‘La Negrita’ with tremendous emotion,” she said. “She was his emissary to life as a man.”

Supported by the powerful Spanish network in Cuba, Alberto learned to maneuver the business world in a way that would serve him the rest of his life. Supportive and protective, the Cuban Spanish network was as faithful to its members as any Jewish or Chinese network in the world. Later, he found the Spanish network to be as equally powerful in Mexico as it had been in Havana. A man now and successful, Fuente saw bigger opportunities to earn money with his skills. In 1924, he boarded a ship for Tampico, Veracruz. He surprised himself by loving Mexico even more than Cuba. He discovered a personal freedom he never thought possible. Within seven years he owned a successful hotel and restaurant and was making money faster than he could bank it. The Spanish network in Cuba had taught him to form associations with all kinds of people, in and out of the business world, and in 1932 he was asked to join the secret order of the Masons. He was later expelled for his forthright opinions about politics and the PRI party.

“Dios, when he drank he criticized Mexican politics and the Catholic church in front of anyone who would listen. God, he was so outspoken! He was furious that when he first came to Mexico everyone could make money, but when the PRI came to power only the PRI guys would profit. All his life he held to the Spanish attitude, “a politician might be a thief, but a good one lets everyone take a share.”

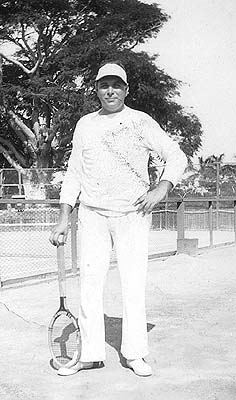

“After the Masons kicked him out,” she continued, “he pursued his freedom like a crazy man. He brought Joaquin, his older brother, from Cuba to manage his hotel and restaurant. He lived the life of a playboy. He played tennis everyday and drove one of the first convertibles, a bright red one, ever seen in Mexico. Soon he had to live in Mexico City because the best clubs and the most beautiful women were there. He moved there and had an incredible apartment in Chapultepec. He met everyone in the business world in Mexico at the time. He lived the ‘high life’ he used to tell us. But his absence from the business in Tampico turned disastrous. Five years after Joaquin took over, the business was bankrupt. They argued terribly for five months until my father discovered Joaquin’s appetite for gambling. After that he severed all ties with him and eventually with the rest of his family in Spain.”

“After the Masons kicked him out,” she continued, “he pursued his freedom like a crazy man. He brought Joaquin, his older brother, from Cuba to manage his hotel and restaurant. He lived the life of a playboy. He played tennis everyday and drove one of the first convertibles, a bright red one, ever seen in Mexico. Soon he had to live in Mexico City because the best clubs and the most beautiful women were there. He moved there and had an incredible apartment in Chapultepec. He met everyone in the business world in Mexico at the time. He lived the ‘high life’ he used to tell us. But his absence from the business in Tampico turned disastrous. Five years after Joaquin took over, the business was bankrupt. They argued terribly for five months until my father discovered Joaquin’s appetite for gambling. After that he severed all ties with him and eventually with the rest of his family in Spain.”

“The first time he returned to Spain to visit his family was some twenty years later, when I was a teenager,” Isabel remembered. “And then when I saw them a few months ago, my resemblance to Maria Theresa and Martin’s reaction to that, somehow repaired that old argument. When I think how destiny used me to make this repair I feel humble and small and grateful… and overwhelmed by the enormous net that holds us together. In the end, time means nothing.”

At 5 a.m. Eusebio abruptly stopped chanting. He stood up from his chair and walked off into a dark area of the garden. Two young men, affluent Guadalajarans by the looks of them, had come through the gate about forty minutes earlier and joined the circle. One of them sat next to me and I watched him pull out two peyote cacti from a pocket and eat them, one right after the other, strychnine tufts and all. About twenty minutes after that he’d vomited twice, and was now deeply affected by the drug. He sat quietly, rocking back and forth and humming. I stood up and placed more wood on the fire and walked toward the terrace where I talked for some time with a woman who spun a rotary calendar to calculate my constellation in the Mayan cosmology. She told me my assignment in life was to catalyze transformation. I thanked her and was aware that my mind felt extremely clear and agile. I had no sensation of dizziness, felt no nausea and experienced no extremes of emotion. Neither my mind nor my body felt weary, although I’d been awake and active for close to twenty-two hours. Mostly I felt an enhanced integration of Self. I looked at the full moon and felt myself held securely in the net of that larger purpose that Isabel had talked about earlier. In a moment of clarity I saw my place in the universe and claimed it. Shortly thereafter I found Isabel standing in the garden hugging herself for warmth and looking at the moon. We linked arms and headed toward the kitchen once more to steam tamales and pound apart circles of chocolate for our guests. While we worked she continued her tale.

“After selling whatever assets were left from the restaurant in Tampico, he went back to his home in Mexico city and started looking for a way to rebuild. He found it in Tlaxcala. He found sources for zacatón, a fiber from cactus we used to use for ropes and mattresses. In five years he was successful enough to be invited to dine at the governor’s table. Imagine! His networking was so good that he got the accounts for the country’s biggest manufacturers and importers, like Clemente Jacques, Los Puros cigars, Martell Cognac, and other companies that I don’t remember now.”

In 1941 Alberto moved north and west of Mexico City to Culiacán, the next big city north of Mazatlán. It became the epicenter of his work and personal life for the next decade. He continued to mix plenty of pleasure with his work, meeting women at dances and continuing to prove himself a veteran playboy. During the ten years he lived there, he traveled extensively and as a result of his connections landed the distributorship for both Corona and Pacifico beers. Corona was then manufactured by a Spanish family in Mexico City and Pacifico was owned and manufactured by Germans in Mazatlán. The distributorship required that he relocate to Los Mochis on Mexico’s northwest coast. From there he oversaw one of Mexico’s earliest large-scale trucking endeavors, bringing the county’s first trailer trucks across Mexico in the ’50’s. It was a daunting task as the country’s roads at that time were miserably inadequate. He prevailed however, and quickly prospered because of his superb organizational skills and experience.

“He could always translate the dream of an idea into reality,” Isabel mused finally as we watched the sun rise from our place in the circle. When the first rays of light shone through the trees Eusebio stood from his chair, raised his arms in a simple gesture, and ended his chanting. Without fanfare he walked into the house, climbed the stairs and lay down on the bed in Isabel’s guest room. Those who remained stayed seated in the circle for a while or collected their things and made their way to the garden gate.

“He absolutely loved his life in Mexico. He never failed to marvel at how beautiful the natural world was and how warm the people were. He was always incredibly grateful that Mexico gave him fifty years, his wife and his children, and his working life. But, you know, he always felt like an outsider. All through my life we had foreigners in our home, I suppose because a part of him knew what it meant to be an immigrant. He used to say it was ‘a lonely, privileged place between two worlds.'”