Did You Know…?

The author of the famous poem “The Bells of San Blas” had never ever visited the town.

The San Blas that the poem refers to is in the state of Nayarit, on the Pacific coast. Today, it is a small town, with several good hotels and restaurants. Close to the town are a variety of habitats, ranging from sandy beaches and mangroves to plantations and swamps, that have led to ornithologists designating the area a “Birding Hot Spot”. Any keen ornithologist staying here a few days is guaranteed to see dozens of species of birds. In fact, about 500 different species have been recorded in the immediate environs of the town, or about 50% of all the species ever recorded anywhere in Mexico.

The town’s economy was not always geared to tourists. For more than a century, San Blas, officially founded in 1768, functioned as an important boat-building center and port. The vessels built in San Blas included those used by Junípero Serra to establish missions in California. To ensure safe passage, a church dedicated to “Our Lady of the Sailor’s Rosary”, and housing the bells, was built on the steep-sided Cerro de San Basilio, which overlooks the town. To ensure that taxes were paid on imports, an imposing customs house was built on the shore.

Time conspired against the port of San Blas. The harbor silted up, the coastline gradually inched its way further west. Other ports, such as Acapulco and Mazatlan, became more important. The town declined. The customs house and church were abandoned, transformed from bustling buildings into evocative ruins. By the end of the nineteenth century, the port was a “has been”.

In March, 1882, far away from Mexico, in Cambridge, Massachusetts, the American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow lay dying. Longfellow was born in 1807 and became a prolific poet and accomplished linguist, speaking several European languages. Now, after a long and illustrious career, his life was drawing to an end, even as the distant port of San Blas was falling into disuse.

Coincidentally, the March 1882 issue of Harper’s new monthly magazine (Volume 64, Issue 382) contained an article by William Henry Bishop, entitled Typical Journeys and Country Life in Mexico. Bishop’s article included brief descriptions of several Pacific coast ports, including San Blas:

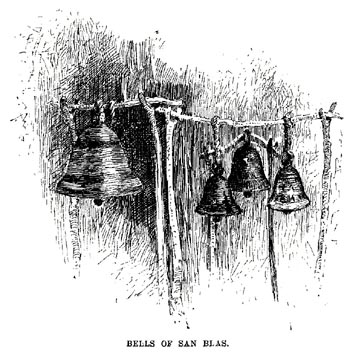

“Acapulco has the most complete and charming harbor, and an old fort dismantled by the French, of the order of Morro Castle. Manzanillo is a small strip of a place on the beach, built of wood, with quite an American look. The volcano of Colima appears inland, with a light cloud of smoke above it. San Blas, larger, but still hardly more than an extensive thatched village, has, on a bluff beside it, the ruins of a once more substantial San Blas. Old bronze bells brought down from it have been mounted in rude frames a few feet high to serve the purpose of the present poor church, which is without a belfry, and this is called in irony ‘the Tower of San Blas.'”

The article was accompanied by an illustration showing four bells swinging from a rickety wooden frame.

new monthly magazine that sparked Longfellow’s

poetic imagination.

After seeing this article, and its accompanying illustration, Longfellow wrote what would prove to be his last poem on March 12, 1882, entitled “The Bells of San Blas”.

Like the port of San Blas by the end of the nineteenth century, the “Bells” had become relics from a byegone age:

They are a voice of the Past,

Of an age that is fading fast,

Of a power austere and grand;

When the flag of Spain unfurled

Its folds o’er this western world,

And the Priest was lord of the land.

The chapel that once looked down

On the little seaport town

Has crumbled into the dust;

And on oaken beams below

The bells swing to and fro,

And are green with mould and rust.

In his comprehensive biography of Longfellow (Longfellow: His Life and Work, Little, Brown & Co., 1962), Newton Arvin writes that the sketch of the bells “was enough for Longfellow’s purpose. Bells had always spoken to his imagination with a special force, and these rather pitiful church bells, once so grandly housed and now so meanly exposed, without even a belfry around them, spelled for him the whole grandeur of a proud and powerful past, both in the state and in the realm of faith — a past that one can only look back upon with reverence but that it is folly to attempt to revive. Longfellow represents the bells themselves, in a few of the stanzas, lamenting their fallen condition and praying that they may some day be restored to their old pre-eminence.” The poem originally ended with the stanza:

Then from our tower again

We will send over land and main

Our voices of command,

Like exiled kings who return

To their thrones, and the people learn

That the Priest is lord of the land!

However, three days later, on March 15, Longfellow changed the ending by adding another stanza:

O Bells of San Blas, in vain

Ye call back the Past again!

The Past is deaf to your prayer;

Out of the shadows of night

The world rolls into light;

It is daybreak everywhere.

In the words of Arvin, “He had had, no doubt, a premonition that his death was very near at hand, and he did not wish to leave as his last word an expression of backward-turning regret for the past, however noble and however devout. The day of pristine hopefulness, in the country he belonged to, had, it is true, gone by irrevocably; it was no longer the age of Emerson and Whitman; it was the age of Mark Twain and Henry Adams. But a despairing last utterance would have been wholly out of keeping for Longfellow, and there was nothing fortuitous in his ending in so sanguine a strain.”

On March 24, Longfellow, who had never had the good fortune to visit San Blas in person, finally passed away. His fame was such that a permanent memorial was made to him in Poets Corner in Westminster Abbey in England.

If you visit San Blas today, spare a thought for this genius of a poet who was able to capture so eloquently the declining fortunes of this once-great port.

Copyright 2003 by Tony Burton. All rights reserved.