Who would have dreamed a train from hell could slice through pristine jungle for two days? We’d have gotten off, escaped, even tried to walk out, except for two problems. We didn’t know where we were, and most of the Mexicans spoke Indian languages, not Spanish. The preceding weeks of restful, carefree travel hadn’t prepared us for this passage.

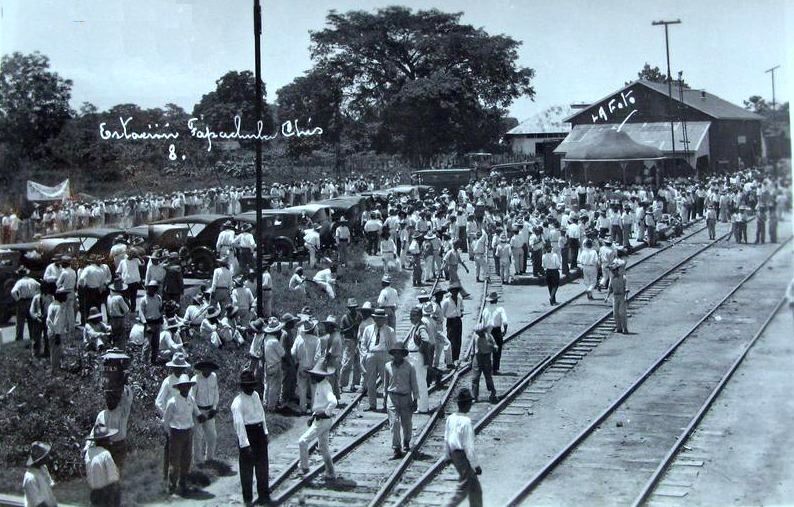

The huge ceiling fan clicked slowly around, keeping the Central American heat from being overwhelming. We left our hotel room in the late afternoon, as we had in mid-morning, only to be greeted by the same spectacle. Hundreds of people, especially children, mixed with a few mounted vaqueros, rushed to the train station as the engine heaved and black soot belched forth. The rails were in Tapachula, Mexico’s main link with the world. Every day, the townspeople welcomed or saw the daily train off.

It was early July 1972, back in what I call my rambling and adventuring days. Married a year, my wife and I bought plane tickets from Tampa, Florida, to Panama, with a stop in San Jose, Costa Rica. We had no intention of going to Panama, but the ticket allowed us to exit in Costa Rica and show the immigration officials we had a paid way out of the country. It was a trick that allowed one-way international travel.

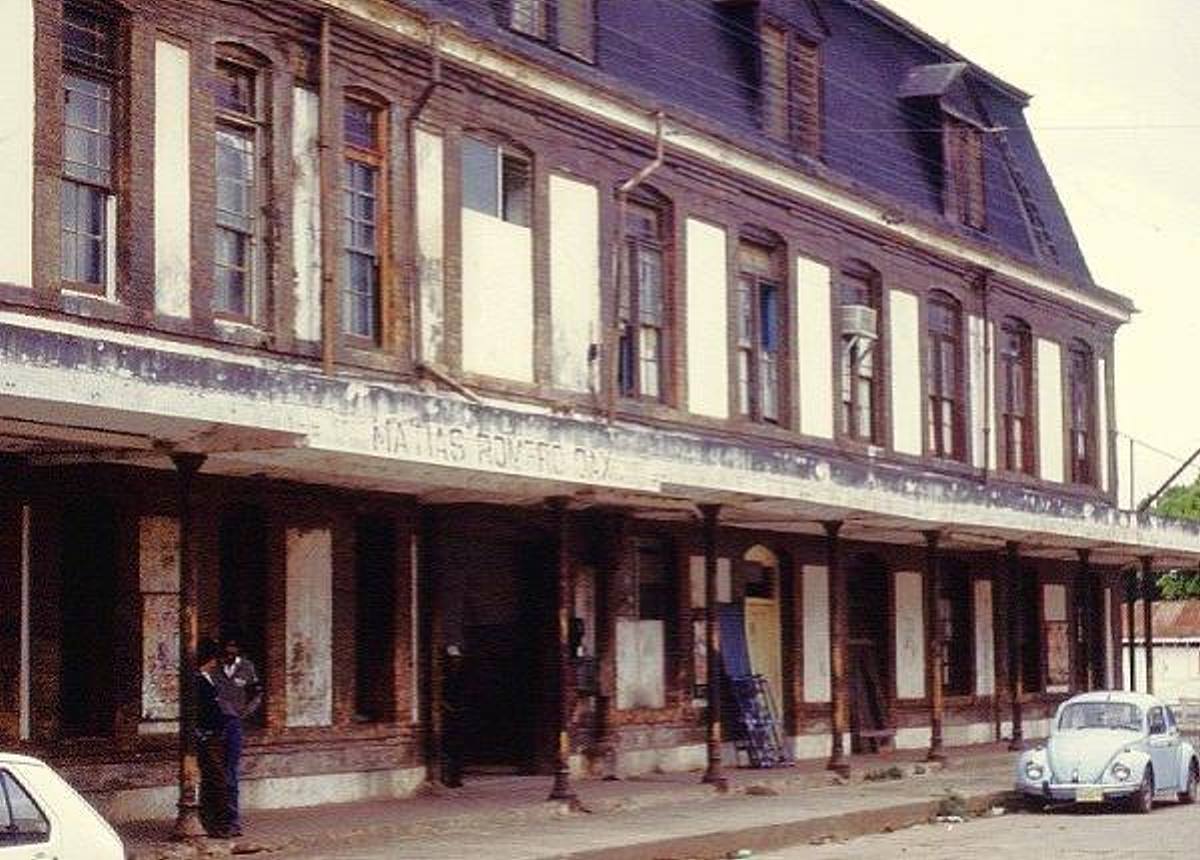

After a thrilling five weeks touring Costa Rica, it was time to return to the United States. The Tico bus ran from San José to Guatemala City. The trip took three days, stopping each night, and rattled through five countries. Entering Guatemala everyone had to exit the bus while workers sprayed clouds of white chemical dust to ensure no pests harmful to animals or crops crossed the border. From Guatemala City, we caught a bus to the border and walked over to Tapachula, Mexico, where we lazed around enjoying the little town before heading north.

It had been a wonderful trip, adventuresome, educational, enlightening and romantic–everything a person could ask for during a carefree youth. We weren’t loaded with money and had to be careful. Surprisingly, my wife, Pam, and I often ordered shrimp. One could get a ten ounce glass of shrimp for about thirty-two cents. The cost in the states would have been five dollars. But shrimp was cheap in Mexico. The dishes I chose turned out to be barely edible to the American palate or had far fewer shrimp in comparison to Pam’s selections. I endured an amazing run of bad luck as we tried different dishes. At Tapachula, it was the worst. I got a few small shrimp over some so-so rice, while she got the twelve largest sautéed shrimp I have ever seen. The largest loomed in excess of twelve inches. They worked their way down to the smallest at about eight inches. Years later, I can recall her shrimp dinner with great envy and the upcoming train ride that counter-balanced all the wonders we’d enjoyed on our journey.

Strolling toward the station, Pam said, “I’ve never ridden a train. Why don’t we see if we can get one to Mexico City or Oaxaca tomorrow?” We’d taken buses, and safely caught rides with people wealthy enough to have automobiles. This was a much different Mexico than exists today, but a train ride seemed like just the right idea.

It was a challenge purchasing train tickets in Spanish for the first time, but we managed. First class tickets for the three-day train trip to Mexico City cost seven dollars each. If I was ever grateful I splurged for first class, it was this time. I don’t know if either of us would have survived riding second or third class.

At nine a.m. the next morning we walked down the dusty dirt street saying adios to a few amigos we made in Tapachula. I wore jeans and an old mustard-colored tee shirt. Pam was the picture of sexy American youth dressed in eggshell white jeans and a crisp white blouse. She anticipated a luxury ride.

Soon, we boarded. The tropical heat and humidity joined the crowd gathering to wave goodbye to the northbound train. The train slowly chugged forward. Passengers hung from the open windows making last second bargains with the vendors running, with bright, unbuttoned shirts, beside the train. It was a three-day and two-night trip to Mexico City. Because Mexico is so mountainous, the train had to cross from the Pacific to Veracruz on the east coast and then back to Mexico City.

In the excitement of watching the town’s people wave goodbye and taking in our fellow passengers, neither of us noticed how dirty the train was. Ten minutes into the trip, Pam leaned over and an eight inch smudge of black showed against her stark white pants. Dirt and filth would be a problem but not the worst: for the train car quickly turned into a sooty, intolerable sauna. The slow moving train never gained speed and jolted along at perhaps, twenty miles per hour, so slow it couldn’t stir a breeze through the open windows.

Dense, rich, vibrant jungle swallowed us. Thick spaghetti-like vines crowded trees. Waxy dry leaves, glinting from the sunlight, were more ominous than anything a Tarzan movie had ever portrayed. The variety of Mexican passengers, all Indians, the new sounds, smells and sights captivated me. Pam, much sharper, was already viewing her train ride with trepidation. Her quickly darkening white jeans and blouse revealed much more to her.

The quaint wooden passenger seats we had enjoyed seeing and talking about when we boarded changed during the first hour. Antique and picturesque disappeared from our vocabulary. Instead they were straight, stiff planks passing for seats. I was thinking my fat behind is a heck of a lot bonier than I’d imagined, but Pam’s chief complaint was, “They’ve been sprayed with coal dust.”

I ignored her early lamentations by running my mouth in limited Spanish or make-do sign language with the always friendly Mexicans. The excitement was still there. I didn’t care that the second and third class passengers had boarded with sheep, goats and chickens.

My only misgiving, as I leaned out the window to look around, would turn out to be the least of our coming troubles: “Damn, I can’t believe it. The railroad spikes are so loose they’re bouncing up and down.”

Sitting on a hard slat for a few hours has a way of taking away from the jungle splendor, the colorful birds, occasional animal life, and glimpses of lone huts or clusters of huts with native life on display. Perspiration soaked our clothes. Evaporation wasn’t a possibility in the humidity. Sweat plopped forth until enough collected that gravity pulled drops downward. Open windows provided only slight relief in the steamy train car, but allowed the billowing acrid smoke to drift in, further choking the car’s already simmering hot air. Still, they couldn’t be closed as there was actually more steam-heat inside of the car than outside. Occasionally, sparks or fire would drift in delivering a quick burn. After many hours, the shy native women realized our rapidly darkening pale-faces weren’t masking fearsome demons from the Northland. They’d bring babies and young children to our forward seat so the kids could escape the worst of the incoming smoke and debris.

Despite her long brown hair being wet, slick, sticky and stringy, I didn’t agree with Pam’s early mumbling, “We’ve entered the Twilight Zone.” She was certain our fellow travelers stared at us as though we were exotic creatures totally out of place on the jungle train. “They have to be wondering what possessed two rich gringos to get on the Mexican train to hell.”

The truth was: any American in those years was a rich gringo to the natives. Our little bit of luggage and the few possessions we carried were worth far more than the wealthiest of our fellow first class passengers. These were poor Indians, but had enough money to spare their families second and third class passage. But what caught our attention then, as it always did in more primitive areas of Mexico and Central America, was these passengers were proud we traveled with them, a part of them. This was a once in a lifetime experience for many of the riders. We were a story. What we did would be related many times in their villages. Surprising me most was the realization the heat and humidity was taking a harsher toll on our fellow passengers than on me. The rolling oven, passing for a train car, was far warmer than the shade in their villages.

The worst reality of hell train hadn’t hit yet. It was waiting, looming just out of sight. When our bladders were full it launched its final horror. I won’t describe the men’s cesspool as I was occasionally able to get off the train and find a tree during a three minute stop. The women weren’t so lucky. The ladies room was a square, bare metal room at the front right portion of our car. It was like a giant metal shower stall with no light beyond what worked its way through a few cracks to reveal a drain hole in the middle of the floor. All waste was deposited directly on the rocks between the tracks. That bathroom remains the most vile, filthy and disgusting room Pam has encountered. You may think trains are a relatively new invention, but this bathroom hadn’t been cleaned since Methuselah’s great-uncle Fritz was in short pants. It explains why she could enter the Guinness Book of World records for going the longest without relieving herself.

By early afternoon I had to agree with Pam’s gloomy assessments. It was apparent there was no escape. It was a monotonous clack-clack-clack except on those rare steep downhill bursts when the occasional clackety-clack filled the air. The reality was an external nightmare. The next thirty-six hours would be a constant torturous rickety ride, while we searched and prayed for a way out. Despite such a realization, hope never completely leaves. The passengers had gotten over the fairness of our skin. Their children enjoyed the few packaged crackers and sweets we had. The question was could all of us survive the grueling ride? Somehow, we had united. Although we withstood the heat better, they had other advantages. None of them would ride the train as far as us and they could drink the water. Even for that relief we were limited to making the small canteen we had last. If we drained the canteen, it would take hours for the purification tablets to work, so we had to just sip. It was the one item we couldn’t share and gratefully water they could safely drink was the one thing they had in plentiful supply.

The train moved slow enough boys walking the track could run along and keep up with it for a hundred yards. Along the way a few villagers here and there would have their belongings along the track and signal. A village wasn’t required as the train would stop in remote jungle and pick up an Indian or two. But the great thrill, the great hope, would arise when the train periodically stopped at a town having in excess of twenty huts. The goats and floppy eared cows ignored the excitement and continued grazing. But isolated humanity is different, and the natives flooded forth from the surrounding jungle and patches of mango and banana trees to see what great mysteries the train might have brought from the city.

We remained a prized and novel experience to these wonderful people, despite our ever darkening appearance. The occasional hand wiping away sweat revealed the wondrous pale skin that drew smiling, “ yi’yi’yi’s” and great admiration from the villagers. It was just too hot and miserable to enjoy our star status. Instead, it was to heck with the wonderful villagers who had never seen a white man. We were interested in the worldly, experienced entrepreneurs in the village. The guys who had moved up the economic ladder to be vendors might have something we’d need. They lugged out huge, American made metal milk pails, which indicated they’d been manufactured in Wisconsin. The dinted pails were filled with the only type of coffee made in Mexico until around the 1980s, with only a few exceptions. They held tepid, overly sweet coffee with plenty of unpasteurized milk to sell along with a few tamales their wives prepared. There was never a sign of a cold drink, or even a canned drink we could have purchased to help with our thirst. Ice was a dream, but something the people had never been seen or even heard of in these settlements. Still, these stops were frequent, and for a moment or two we could jump off and enjoy temperatures twenty degrees cooler than in the car.

Unfortunately, each stop always gave Pam hope a village would have enough population to support a store and perhaps even a road that would lend itself to her escape.

At dusk the second day we arrived in Veracruz, feeling beaten, battered, dehydrated and distraught. Veracruz felt like the next thing to heaven. We were free, ice was rare but a reality, and we didn’t give a damn about people staring at our haggard appearance. We had an hour layover, and after draining all the lemonade and cold drinks we could hold, I felt better. “Let’s hop back on for Mexico City.”

Her stern, wide-eyed stare brought me back to my senses. We found a hotel where we could soak away six months of grime gained in two days and hire someone to burn our clothes.