Mexico City has some of the best street/urban art murals in the world, but almost all the attention in the press is focused on work done in the center of the city. In reality, much of the best work is being done on the east side of the Mexico City Metro Area (MCMA).

Modern street art as an extension of “classic” Mexican muralism

The muralism of Diego Rivera and company fell out of favor with Mexico’s avant-garde starting in the 1950s, but its impact is still felt today. Murals of that style are still painted on government buildings. However, the arrival of graffiti in Mexico in the 1980s may have spawned muralism’s true heir: street/urban art murals. Like their predecessors, many of them address social issues and cultural identity. Perhaps the only real difference is that the murals are done by socially-marginalized youth with spray paint, instead of by classically trained artists.

This is particularly true of the work being done in the poorer areas of the metropolitan area such as Iztapalapa, Ecatepec, Ciudad Nezahualcóytol (Neza for short) and others on the east side the valley, where Mexico City proper meets the panhandle of the State of México.

NY-style graffiti took off by the late 1980s and early 1990s, and, just as quickly, it was denounced by authorities who set up a special anti-graffiti unit and even jailed some grafiteros. But, at the same time, academia and the counterculture started taking notice of the growing phenomenon in writings, documentaries and more.

The appearance of murals done in spray paint, coupled with the failure of punitive action, led governments to relax their prohibitions, and accept that the murals had artistic value. In the 2000s, artists were invited to paint temporary construction walls and, after public approval, permissions to paint permanent structure soon followed. Such murals have been proliferating ever since.

It has led to a distinction by many (but not all) between ‘graffiti’ (produced, usually in the form of letters, without permits) and ‘street or urban’ art, always done with permission. The latter has allowed artists to develop sophisticated techniques, not only with spray paint, but also using other techniques such as acrylics and stencils.

Despite the city center’s prominence and prestige, some of the largest mural projects have been done in marginalized areas. Iztapalapa, Neza and Ecatepec have sponsored events and projects resulting in dozens, indeed hundreds, of murals. For artists, it is satisfying to beautify neighborhoods, create messages about what concerns them and, sometimes, even get paid.

Sponsorship

Like the other arts, only a select few street/urban artists make any significant money with their work. Most individuals began as grafiteros and then made the shift to murals as their skills developed. This is the case with Miguel Angel Junco, who began tagging clandestinely as a child, but later became not only a muralist, but also an academic specializing in documenting this phenomenon.

Many of these artists belong to informal or formal groups, he says, starting out with little or no money, meaning they use their own resources to paint. Some are fortunate to attract sponsors like the Carlos Slim Foundation or municipal authorities. The latter, by far, are the biggest sponsors, as they look for a cost-effective way to battle the sea of gray, unpainted cinder blocks that make up much of the low-income residential areas.

Topics of the murals

Although graffiti in Mexico started off copying that done in New York, its street murals have evolved in their own way, especially in imagery and color schemes. Here is where you see the influence of the old muralism – art in service to the community, interested in Mexican cultural identity, critique of social ills, and artists’ visions of a better future.

Common images include Mexico’s various peoples and cultures, local and national heroes, and in the realm of social criticism, migration, poverty, violence against women and environment. Interestingly, few, if any, criticize the government, most likely because it, and those associated with the ruling class, are patronizing street artists. In fact, Junco calls government patronage a “double-edged sword” as graffiti becomes politicized.

Hotbeds of muralism in marginalized MCMA communities

Ironically, it is relative poverty that makes east-side communities well-suited for street murals. Most residents have barely enough money to build their homes bit-by-bit, and cannot generally afford painting the outside of their homes. This results in endless swaths of unpainted gray walls, and municipalities see the engagement of artists as a cost-effective way to combat this, as well as showing a very visible message of “we are working for you.”

Ecatepec began sponsoring large-scale mural projects more than a decade ago. These projects and art festivals have attracted street artists from all over Mexico and beyond. One of the first was a project to line Pope Francis’ route through the city in 2016 with 50 murals related to Catholicism and Mexican culture.

From 2019 to 2023, the city has sponsored over 480 murals in various areas, many of which are part of the #LaCalleEsTuya initiative, which seeks to “[recover] housing and neighborhoods… [and] improve them with art and color, in areas… that are profoundly affected by crime.”

One interesting incentive to paint comes from the city’s Cablebús line—a cable car taking commuters over congested streets and hills. The route hosts many of the murals, not only on the sides of public and private buildings, but on some rooftops as well.

Neza started a little later, but this year has budgeted 8 million pesos for murals with themes such as violence against women, mental health, sexual and reproductive rights. This project commemorated International Women’s Day and included murals in the local teacher’s college, bringing street art into an educational setting.

One curious project in 2019 paid tribute to the movie Roma, as part of a project called “Todos los caminos llevan a NezamoR” (All roads lead to Neza-love). More than twenty artists participated, and Roma‘s director, Alfredo Cuarón, came to view the murals.

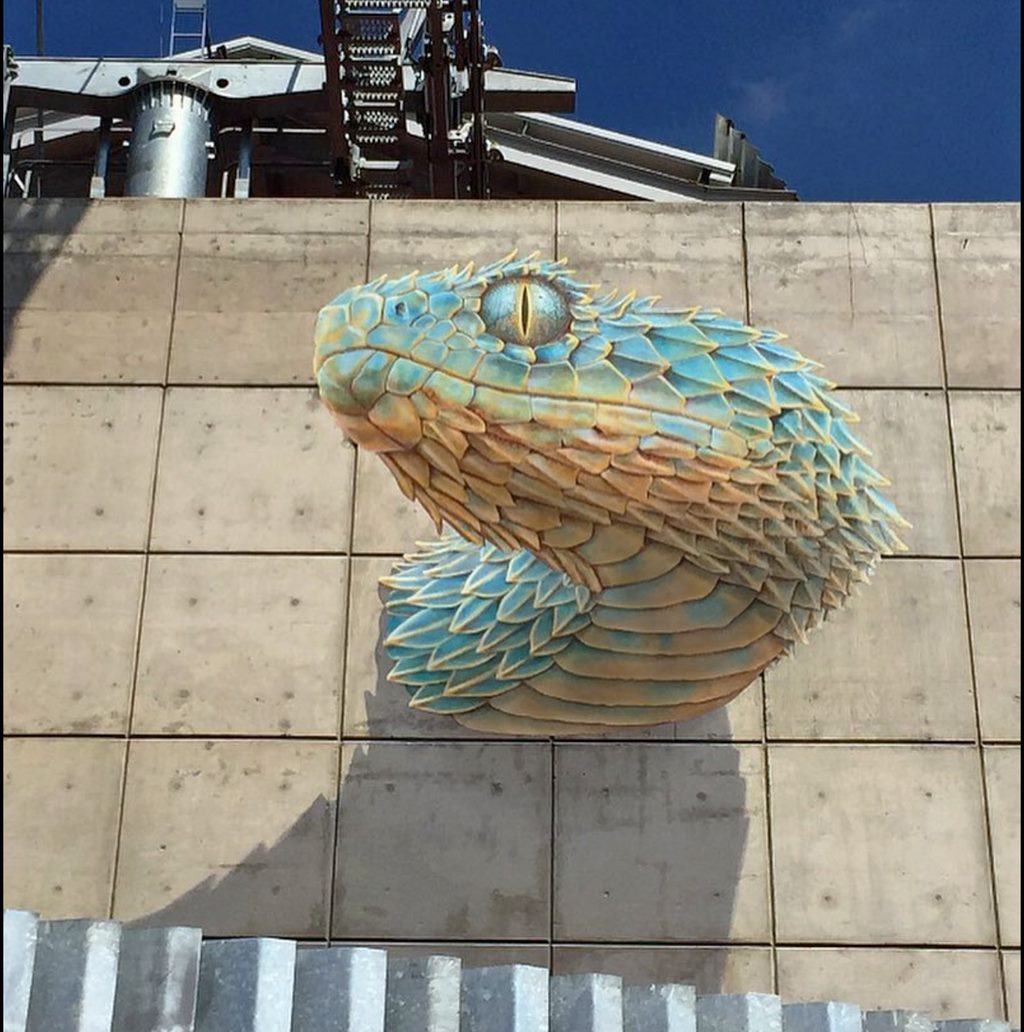

![One of the murals of the mega-10,000+ project in Iztapalapa. (CC BY-SA 4.0) [Wikimedia Commons]](https://www.mexconnect.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/2048px-Mural_iztapalapa-s.jpg)

Challenge for street/urban artists in the MCMA

All artists struggle, but street/urban art has some special issues. The most common is vandalism of their work by grafiteros who paint names and letters over days or even weeks of work. It has happened on murals of all types and in all parts of the city, even those painted by famous international names.

Street art tour guide Chris Lüders told me, with a resigned shrug, that “It’s the graffiti artists’ way of saying, ‘These are our streets too.’” A street art patron, Roberto Shimizu, added that some vandalism by grafiteros is a form of “street curation”: essentially, they deface murals they do not like while leaving the ones they approve of alone. Such risk is part of what makes street art often ephemeral, alongside the fact that acrylic and spray paint fade and peel over time.

One recent issue is that murals sponsored by NGOs and governments can lead to gentrification of neighborhoods. This seems to be the case for a section of the historic center near the Sor Juana University. In his master’s thesis, Junco notes that the invitation of the international organization Meeting of Styles succeeded in bringing attention to the area, once a forgotten part of the city. It now has new bars, restaurants, and residents with far greater means than the ones they replaced. Although far safer than it was 20 years ago, there are complaints that the murals give a “false sense of culture” says Junco, even though visitors do little more than drink alcohol.

Junco does not believe that the major mural works in places like Ecatepec, Neza and Iztapalapa will lead to gentrification there, in part because those areas have relatively little else to offer. He says governments there are more interested in “recovering public spaces” from crime. This may be true in the short run, but with the skyrocketing cost of housing in Mexico City, it may not be true forever.

Whatever you think of graffiti, street murals and the low-income parts of the metro area, the rise of street/urban art on the east side of the city is an important experiment in whether Mexico’s love affair with murals can also make a difference in its social fabric.

Leigh Thelmadatter is a freelance writer whose first book, Mexican Cartonería: Paper, Paste and Fiesta, was published by Schiffer in 2019.

Related articles on MexConnect

- Graffiti: the wry humor of Mexico City street stencil art

- Graffiti: the Estadio Azteca and Mexico City’s new wave muralists

- Graffiti: Mexico City’s wall art emerges from the shadows