From the book “CASA MEXICANA” ©1989 Tim Street-Porter, published by Stewart, Tabori & Chang, New York.

Reproduced by special permission of the publisher and author.

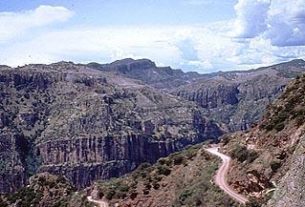

The haciendas were the landed estates of Mexico, some with territories as big as Belgium. For visitors to Mexico, they conjure up surreal images of ruined palaces; still possessing a faded grandeur, dominating a desolate landscape of cactus and agave. Before the revolution of 1910, when their lands were confiscated, the haciendas (a term which referred either to the estate or the often huge house of the owner) made up a high percentage of Mexico’s agricultural land, and their collective power was enormous. Each one was a rural, autonomous social unit with its own history, and for each, myths accumulate over the centuries.

Haciendas were created under a system established in the sixteenth century, which bestowed land to conquistadores and other Spanish notables in exchange for military and social services to the crown. These land grants were limited to a few hundred acres, partly for security reasons (there was the fear, based on European experience, that huge estates might eventually pose a threat to national security). Over time these estates invariably grew. The hacendado (or owner) might buy neighboring ranches; often he would simply appropriate Indian land. As the haciendas grew, they became feudal estates supplying all the needs of the surrounding community, including food, clothing and medical aid.

Haciendas played host to a variety of activities from baptisms, weddings, and celebrations of saints’ days to fiestas, charro (cowboy) parties and contests, bullfights, and harvest festivals. Travelers who stopped for the night, whether invited or not, were treated to displays of hospitality, particularly in the more remote regions, as described in this report from Santa Inés in 1828: “We arrived at about 3 o’clock…and the relics of the dinner brought forward for us… We spent the afternoon in the shade on the terrace, chatting, smoking cigars with the ladies… the Marqu¦eacute;s de Salvatierra, with his lady and family, the Marqués de Santiago, and his sisters; miners, soldiers, lawyers – and priests, of course. Besides our worthy host, Don Antoñ’io de Michaus, we made the number of guests twenty-four, and for the most part they had come — like ourselves — au hasard, uninvited and unexpected, but sure of a hearty welcome and good fare.”

The hacendado and his wife had various responsibilities as community leaders. He might be called on to act as judge, and she often toured the estates, ministering to the sick with the simple remedies available at the time. Mescal was pressed into service as a universal cure-all, from a rub down for sprains, to a treatment for colds and the grippe. Its virtues were summed up in a popular saying: “good for what ails you and also good if nothing ails you.” It was even used as a measure of distance; the hard drinking hacendados often referred to a nearby village as “one bottle of mescal from home.”

The charro played a similar role in the life and folklore of the hacienda as did the cowboy on the American ranch. His horsemanship skills, his elaborate and elegant clothing and accoutrements, his music, and his pride and personal style were every bit the equal of those of his cousins across the border. The tradition of the charreada (rodeo) is still kept alive in the haciendas of today, and the charro has become a symbol of nostalgia for the traditional rural life of Mexico.

For the Indian population whose lands had been appropriated by the hacendados, hacienda life was often less romantic and rosy than diaries describing social visits to the haciendas might suggest. Deprived of their own land, the Indians were forced to work on the haciendas as peons, and had little choice but to buy everything they needed form the hacienda store, further increasing their dependency.

The relentless growth of the haciendas was not due to a need for, or even interest in, increased production but was usually motivated simply by the prestige that went with substantial land ownership. Only about 10 percent of hacienda land was ever cultivated. Once acquired, most of this land which had once been carefully cultivated by the Indians was left as derelict pasture.

Haciendas usually concentrated on one particular agricultural product, depending on the region: mescal in Zacatecas, sugar in Morelos, sisal in Yucatan, pulque (the alcoholic beverage produced from the agave plant which, when further distilled, becomes mescal) in Hidalgo, and cattle in Querétaro. Around the haciendas, and administered by them, were smaller ranches which supplied grain and other seasonal crops.

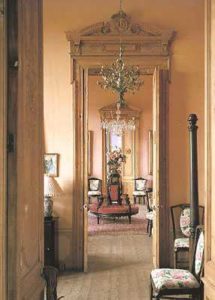

By the eighteenth century a typical hacienda was an elaborate institution. In addition to the main house and its guest quarters there were stables, a general store, a chapel, a school, equipment stores, servants’ quarters, granaries, corrals and a forge. Clothing was produced at the hacienda from cloth woven on the premises.

The haciendas grew in size during the centuries of colonial rule. In 1821 Mexico became an independent nation, but lapsed into a period of decline and economic upheaval. From 1864 to 1867 the French occupied Mexico with Maximilian and his wife Carlota installed as Emperor and empress. This intervention was brief, but it began a period of French influence in architecture and culture which lasted will into the twentieth century.

From 1876 until 1911 Porfirio Díaz ruled Mexico as dictator, restoring it to economic strength by the use of capitalist measures and the encouragement of foreign investment.

Earlier in t he nineteenth century there had been failed attempts by liberals to dissolve the haciendas and restore their land to the Indians. Díaz did the opposite, making extra land available to establish new haciendas and increasing the size of many existing ones. During his rule many haciendas were given a face-lift, usually in the form of a proud neoclassical style reflecting the new national confidence.

Meanwhile, living conditions declined further for the majority of Indian peons working on the haciendas during the Díaz regime. It is a situation best described by Henry Bamford Parkes, in his book A History of Mexico. “Courteous, sensual, and decadent, with charming manners and with nothing to live for except pleasure, the hacendados lived in the City of Mexico, or more often in Paris, drawing revenues from the lands which their ancestors had conquered or stolen from the Indians and leaving them to be managed by hired administrators… When, once or twice a year, they visited their estates, the peons were given a holiday, and the owner and his wife would distribute gifts and pride themselves on the happy faces of their dependents. Of the actual lives of their peons, of how the administrators would beat them and torture them and claim feudal rights over their wives and daughters, these absentee owners remained blissfully unaware.”

The revolution of 1910 – 1920 finished the haciendas. The enlisted troops of Pancho Villa, Venustiano Carranza, and Emiliano Zapata roamed the country, burning and pillaging every hacienda they could find. The lands were restored to the Indians and landowners subsequently were allowed only 200 acres.

Haciendas today are often still owned by descendants of the older hacendados. Others have been bought since the Revolution by Mexicans from the city wishing to have a place in the country, and some have become hotels and conference centers. Most of those which are occupied today have undergone complete renovation, since the burnings and sackings of the evolution left some with little more that the basic walls.

Further Articles from the ‘Architecture of Mexico’ Series:

Architecture of the Pacific Coast -|- The Houses of Luis Barragán