The yearly “Fiestas de Santiago” was going full tilt. And I truly mean tilt, because at 5 o’clock in the afternoon, I noticed quite a few local residents in a very happy mood due to the consumption of copious quantities of alcohol, another tradition.

This party is held for a week every July in the small town of Santiago, just outside of Manzanillo. There’s a carnival, nightly dances in the bullring, special sales, and the event I had been invited to, the charreada.

A charreada, a popular Mexican event, is basically a rodeo, a competitive proving ground for a new type of Mexican cowboy–the brave and proud charro. Historically, Mexican cowboys (vaqueros) held contests among themselves to show off ranching skills such as bronco riding and roping. These early cowboys were Indians or mestizos (people of mixed-blood–usually Indian/Spanish). They developed their skills of roping, branding and rounding up cattle in the new Mexican enterprise of cattle ranching, after the Spanish conquistadors introduced them to horses and cattle.

Since they were mostly strong, brave men at that time, many were “roped” into fighting for their country. They are featured in the first few lines of the Mexican National Anthem, and are honored throughout the country on Charro Day, September 14. They also participate in local parades, and each year hold a place of honor in the country’s Independence Day parades on September 16.

Today, these rodeo showmen have refined their act so that they provide high quality entertainment to the rodeo aficionados. It is a recognized sport with strict rules to be followed during the competitions, in which both men and women participate. The intermissions (while the next bull and rider are getting ready), are enhanced by throbbing “banda” music, while couples dance Mexican “salsa” in the aisles.

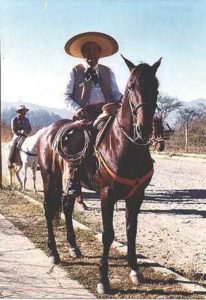

My friend and charro, José Abel, invited me to the charreada in Santiago, beginning with a free lunch and drinks for all participants and their families. I was two hours behind schedule because of my work, so I missed the food, but there were a few hangers-on ready to offer me tequila añejo (aged tequila) or an ice cold Corona. This is pretty normal if you’re the only blond gringa (foreigner) in the place. After accepting my tequila, a plastic cupful on the rocks, I noticed that even the charro’s horses were given a place of honor at the dinner. I was delighted to actually see up close a true pro working his horse in the dining area while the live band provided ear-splitting Mariachi music. I even noticed one performer giving his stallion tequila!

To locate the charreada, I just followed the charros and fans to the bullring. There was a long line, but as an honored guest of a charro, I was waved right through and found a good seat on the shady side of the arena. Vendors were circulating, hawking everything from ice cold beer to various Mexican snacks, all with pre-packaged spicy salsa. Following the vendors, children were walking around collecting the aluminum cans for recycling.

Being the only blond woman in the place, everyone stopped to say hello, and ask questions. My poodle, Sunny, was a particular hit with the kids. José Abel rode over to give me a Mexican salute (with a Sol beer, of course), from the ring. While normally the charros wear colorful costumes with silver studs, this July day in Santiago they were outfitted in typical cowboy attire: jeans, a western shirt, cowboy hat, and boots with spurs. The humid, 90-degree afternoon may have had something to do with it.

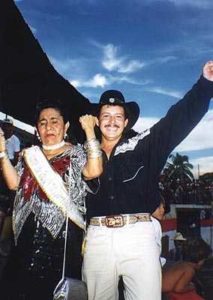

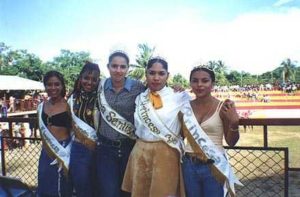

A former rodeo queen (from perhaps 50 years ago) stopped by to do a little dance for me, while posing with one of the charros. The current queen and princesses of the charreada, dressed in cowboy attire, cheerfully smiled for my camera. I was having a great time, bolstered by that cup of tequila.

As the event commenced, I could feel the tension build in the audience, the band stopped playing, and all became quiet. When the first bull and rider charged out of the gate, a cheer went up, but the contestant lasted only about 5 seconds before he was thrown off, landing directly under the bull’s stomping feet and sharp hooves. (The bull rider must stay on for a full 10 seconds, holding the rope halter with only one hand to qualify, just like in U.S. rodeos.)

When the rider’s butt hits the dirt, that spurs the charros into action. They protect the bull rider from the enraged bull, rope it, and get it back to its pen. Bull riding can be very dangerous, and sometimes, even the best efforts of the charros aren’t enough. The day before I attended this charreada, I read in the local paper that a contestant was gored by one of the bulls and hospitalized.

During this event, I saw one of the charro’s horses seriously injured after being gored in the flanks. True to tradition, the charro remained in the ring, riding his wounded horse, until the bull was subdued and the rider was safe.

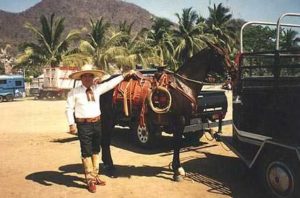

Charros sometimes travel many miles for the competition. My friend José has a modern horse trailer for his stallion. (To geld a horse is unheard of!) He lives on a large ranch just outside the town of Santiago. He has several saddles for his horse, but his silver-inlaid saddle and bridle have a place of honor in his bedroom.

José Abel actually owns a nursery in Baja California, but attends every charreada for miles around. His ranch, near Manzanillo, is simple but not primitive. He has a swimming pool fed by a natural spring aquifer. Because he owns a nursery, the yard is filled with many different species of flowering plants and trees, as well as banana, mango, papaya and lime. Five different species of palm trees provide shade and cool breezes for the many fiestas he holds throughout the year, where carne asada (grilled meat) is served to his guests. I once attended a fiesta at his ranch where venison was served. It happened that a deer fell into his pool and drowned, hence the reason for the party.

By nature, all charros are a bit “macho” as the tradition demands. After a few belts of tequila before the event, the charro is ready to face the risks and the broken bones. He is truly a “man’s man,” a tough guy who holds a permanent place among strong horses and rough company.

Charros usually start their training as small children (“charro-ism” is oftentimes a family tradition), and learn to perform rope tricks and fancy horsemanship on finely-trained steeds, along with bull riding, bronco riding, and steer roping. José started his training as a small child, where he practiced rope tricks, bull riding, bronco busting and steer roping. He says his sport is a living history, an art form developed from actual skills of a life working on the ranch. Soon, he’ll be taking a 4-day trail ride/cattle drive with other charros, to move his cattle to the mountains and greener pastures for the winter. They’ll camp out, sing Mexican ballads, and drink agave gold until they get the cattle to their winter grazing ground. Then, in a small town in the hills, 8,000 feet above Manzanillo, they’ll participate in a local charreada, once again celebrating being a brave and strong charro!

Words of the first stanza of the Mexican National Anthem:

Mexicanos al grito de guerra

El acero aprestad y el bridon.

Y retiemble en sus centros la tierra,

Al sonoro rugir del canon.

Mexicans, at the cry of war

Make ready your sword and your horse

Let the foundations of your land resound,

To the sonorous roar of your cannon.

One charro explains it this way: “We are the warriors of Mexico! Our ancestors fought for our independence and freedom, and we celebrate our patriotism by being brave and strong charros!”