Arts of Mexico

Between 1920 and 1940 Mexico went through a period of radical transformation. The revolution had ended and in its wake an energy for transformation was unleashed that was unparalleled anywhere. For the artistic and intellectual community those years were full of excitement and creativity as new identities, personal as well as cultural, were being forged. New ideologies and manifestos sprung up almost daily. Some greatly influenced the next generation of Mexican art. Others died a timely death.

One of the casualties of the new Mexican spirit was the Old San Carlos Academy, now known as the Escuela Nacional de Bellas Artes. In a country where art and the public have always been comfortable bedfellows, it’s not surprising that it was in this institution that a lot of the battle for identity was fought.

The Academy was stuck in its European roots. Emerging Mexico had no time for its romantic sentimentalism or classical and religious tradition. It wanted its own authentic voice.

In fact, artists everywhere, not just in Mexico, were moving away from the purely representational and towards a more personal form of expression. But in Mexico it represented more. Here, artists had a social mission – the establishment of a continuity between Mexico’s pre-Columbian past and the Mexico of their day. The new art had to enroll a country not just a small elite. It finally found a home in the Muralist movement and in a redefining of the sculptor’s aesthetic.

A vast body of art was produced between 1910 and 1950, but most attention has been directed towards the two dimensional work. Less attention has been given to the sculpture of the period even though a number of the “new age” sculptors were also finding their voice.”

As with the painters, the ideals of the Academy had also lost credibility with the sculptors. They, too, wanted to re-connect with their pre-Hispanic past, in their case with the sculptural tradition. The new vision was to elevate the stone cutter and carver from artisan to artist.

The new generation of sculptors wanted to cut directly into the material rather than build up “little balls of clay”, a condescending turn of phrase published in Forma, one of the art reviews of the day, to describe the process of first modeling the figure and then shipping it off to skilled artisans to translate into stone – a European process favored by the Academy. Both Rivera and Siqueiros, influential voices of the time, spoke out strongly for direct carving – to work the material the way their pre-Hispanic ancestors had done.

The quest was for a visual language that could express the national soul. The emerging generation of sculptors re-discovered the work of the ancient civilizations. They studied the sculpture at the Museo Nacional de Historia. They also looked to the alter pieces and carved relief work on the exterior of the churches that were produced during the vice-regal period.

But, while the sculptors were looking to their indigenous past, they could not and would not lay to rest the European based academic training they had been given. Most were well grounded in the Academy’s basic training and drew from that training. They were taught to be consummate draftsman. They were also taught proportion and scale, and the power of the monumental or the grandiose, not just size for its own sake.

What they moved away from was classicism. What they embraced was a more contemporary vision to give their work meaning. Their European academic training with their re-discovered pre-Hispanic vision blended into a visual language that was to become uniquely Mexican.

And as much as they looked to their past for inspiration, they also looked to Europe. Science was revolutionizing culture and opening doors to new techniques and types of media. It changed perception and broadened the range of possibilities. The new breed of Mexican sculptors experimented with the new concepts developed by the European avant-garde. They listened with excitement to the Mexican artists returned from Europe after the revolution who further influenced the new way of seeing.

The challenge was to recognize the diverse face of the Mexican culture – the mosaic represented in the concept of “mestizaje” – the racial blending of Europe and the new world, and unite it with the new materials and techniques. They worked in many materials – cardboard, wood, stone, and bronze. They used planes and color to expressive ends. And while some works were massive, curving closed-form figures reminiscent of the old gods, others were small pieces reminiscent of typical Mexican toys.

The breadth of expression and materials used to express this unified identity of a diverse people could not be better typified than in the works created by German Cueto and Francisco Arturo Marin between 1920 and 1940.

German Cueto was born in 1893. When he was 17 years old, he met the sculptor Fidencio Nava. It was a meeting that changed the direction of his life. He dropped his pursuit of chemistry and entered the Academy of San Carlos to study sculpture.

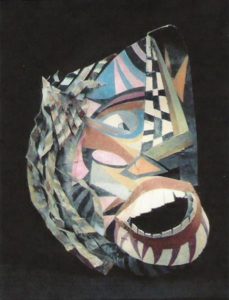

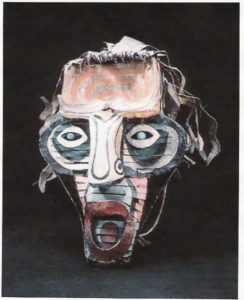

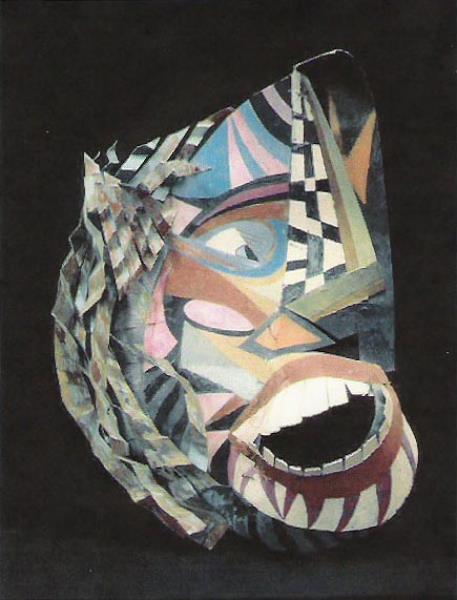

In 1924 he joined the Estridentista movement whose aim was to reshape literature and art from the ground up. The movement was led by the poet, Manuel Maples Arce and was strongly anti-academic. Cueto’s masks were first unveiled to the public in 1924 at the Nobody’s Café, a favored haunt of the Estridentistas. His color saturated cardboard masks exemplified the philosophy of the group.

The Estridentista movement died in 1927, but German Cueto did not. He moved to Paris where he lived until 1932.

While in Europe he met, among others, the modern sculptors, Jacques Lipchitz and Constantin Brancusi. His strong affinity for the language of modern art was nurtured by these associations. He knew by the time he returned to Mexico, the vision he would follow.

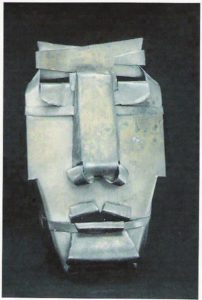

Cueto ranks among the most experimental practitioners of modern Mexican sculpture. His works include ceramics, enamel on metal, and monumental sculptures like “The Runner” made for the Route of Friendship at the XIX Olympic Games held in Mexico City in 1968.

His aesthetic was very much in line with Umberto Boccioni’s 1912 Manifesto of Futurist Sculpture in which he stated that sculptors were free to combine as many materials as they needed to realize their artistic vision. Boccioni went on to say that the abstract reconstruction of plane and volume comprises a work of art, and not its figurative quality.”

German Cueto worked in cardboard and sheet metal. Time and again he returned to his fantastical faces, their empty sockets beckoning the viewers to leave their earthly identity behind and metamorphose into another spirit. Nothing could come closer to bridging old Mexico with the new than the mask. They have been an integral part of Mexican life from pre-Hispanic times to the present where they still play a significant role in the religious and popular festivities of the people.

Cueto looked beyond the roots of his culture to expand his creative vision, and as such his expression has a universal appeal. But in essence, his work unites Mexico’s past with its modern present, and in this sense played a role in the search for a Mexican identity.

Francisco Arturo Marin was also in search of his Mexican identity, but his work took a different direction.

Marin was born in 1907. While in high school, he studied woodcut under Carlos Orozco Romero. After completing a medical degree in Mexico City, he returned home to Guadalajara where he studied direct carving under Leon Muniz and modeling and wood carving with Ortiz Monasterio. He took up carving so that he could work in stone and under Luis Ortiz Monasterio, a masterful manipulator of volume with a strong emphasis on the human figure, he learned a new visual vocabulary.

Instead of exploring the new technologies and “isms”, Marin looked to the aesthetic of his cultural past. Even as a child, pre-Hispanic sculpture excited his imagination. This is the explanation he offered people when they asked him why as a medical doctor he would spend his time sculpting.

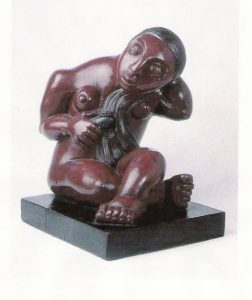

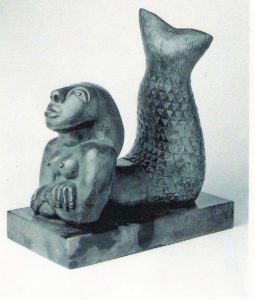

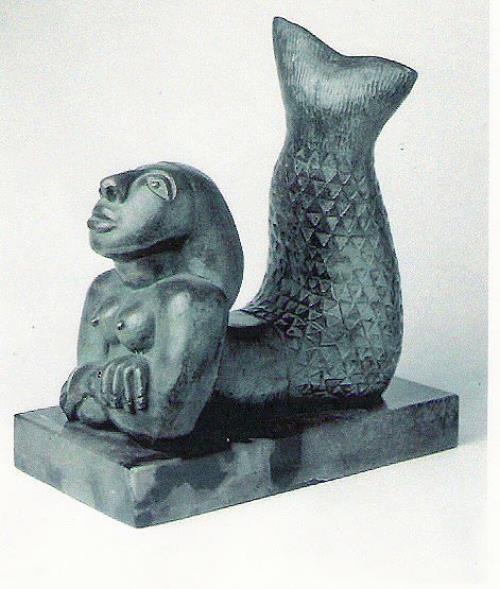

Marin carved closed forms reminiscent of the sculpted gods and goddesses of ancient Mexico from blocks of stone on which he grafted facial expressions and poses. He favored as subjects mother and child compositions and the indigenous themes that dominated the post-revolutionary pictorial aesthetic. But many of the subjects of his sculpture came from his many hours of ministering to the suffering.

One of his monumental works, “Peasant Sacrificed”, can be found in the Ministry of Education. Another work, ” Tribute to Medical Workers”, which he collaborated on with the sculptor Federico Canessi, is located at the 20 de Noviembre Hospital in Mexico City.

Marin is considered a champion of Mexican modern sculpture. His work is said to create a tension between reason and instinct, the vital and the eternal, the material mass and the animate. This description could as well fit the early indigenous work that he so admired.