Beneath the high walls of an ancient crater, you glide across the placid lake in a rowboat, mesmerized. “This is surely the most peaceful place in all Mexico and definitely one of the most beautiful,” you tell yourself. But just beyond those protective crater walls rises one of the most dreaded forces of nature: an angry volcano working itself towards an eventual violent explosion. And then, there are the ghosts….

Laguna La Maria is located 130 kilometers south of Guadalajara, Mexico’s second-largest city and only ten kilometers from the Volcán de Fuego, or Fire Volcano, which offers a fascinating show to guests who wander a few hundred meters up the cobblestone road in the dark to watch the show.

Only the inside of a cave is darker than the road north of La Maria and you may suddenly find yourself face to face with a stray cow if you don’t happen to be carrying a light. But the inky blackness is the perfect backdrop for a pyrotechnic display that few people on earth have seen with their own eyes.

At first, you may doubt that there is a volcano ahead at all, because you may see nothing whatsoever for several minutes. Suddenly, however, a tongue of fire shoots straight up in the air and a cascade of sparks tumble down, revealing the classic shape of the great volcano. Then a blob of red appears at the top and suddenly races downward, producing an ominous roar that triggers an uneasy feeling at the pit of your stomach which very quickly develops into a primal urge to turn tail and run for your life. No fireworks display will ever affect you like the awesome sight and sounds of a volcano venting its fury!

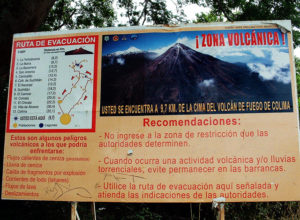

As for the danger involved, the managers of La Maria say that numerous deep canyons between them and the volcano reduce to zero the possibility of lava reaching their lagoon. The real danger, however, is that of a Mount-Saint-Helen’s type explosion, which would — according to a U.S. volcanologist — shoot a cloud of hot, incandescent gases straight towards the city of Colima, burning up everything along the way, including visitors to La Maria. “Sí sí,” say the locals, “but they have been telling us that for years while the volcano just keeps rumbling and spitting in the same old way.”

By pure chance, I happen to be one of the last human beings to have set foot inside the crater of the Fire Volcano. About two months before it erupted in 1991, I got a message from Mitchel Ventura, the man in charge of the University of Oklahoma’s housing facility just outside Colima City.

“The volcano is showing lots of new activity and a volcanologist from the University is coming to study the situation. He’s going to need help to carry some scientific instruments up into the crater. Any volunteers?”

I had no problem finding several members of our caving club delighted at the prospect of hiking up to the famous volcano’s crater, which rises 3,860 meters above sea level. I’m afraid I’ve forgotten the name of the volcanologist, but he regaled us with stories about false predictions of eruptions in various parts of the world, as we slowly made our way to the top, each of us carrying devices in our backpacks for measuring the temperature of hot gases venting out of the crater and the intensity and frequency of tremors.

From the edge of the crater wall we looked down on what seemed like the very picture of Hades. Once inside, we had to tread carefully as there were many spots hot enough to melt the soles of our boots. As the volcanologist set up his instruments — each one with a transmitter that would relay the data to the University of Colima — I walked over to a hole from which gases were hissing. I ripped a page out of my pocket agenda and held it near the opening. In a second, it burst into flame.

After a little while, we took out our sandwiches for lunch, but in those infernal surroundings there was no place to sit down without getting scorched and the best we could do to relax was to lean against a high rock.

By now most of us had headaches and were feeling a bit dizzy. The moment our volcanologist said he was ready to leave, we were right behind him. As we left the crater, I noticed a huge hole in my nylon windbreaker. Apparently one of the rocky outcrops I had leaned against had been hotter than I thought. We successfully made our way back down the volcano, wending our way through giant, often unstable blocks of volcanic rock. Approximately two months later, the crater suddenly filled with lava, burning to a crisp all the instruments we had carried up, and streams of lava began to trickle downward. No one has been in the crater since.

Back to La Maria. When you get tired of volcano watching (if ever), you can always go ghost hunting. “Sometimes you can hear them moving about in the dark or even calling your name,” people told us. We were inclined to believe these stories because several years ago, a group of us were standing near the shore of the lagoon, trying to decide on a good spot to pitch our tents. Suddenly, rocks about three inches (eight cm) in diameter began falling out of the tree we were standing under. This went on for some five minutes while we shouted at the “children in the tree,” asking them to stop the nonsense. However, it turned out that there were no children or animals in that tree and in those days the volcano was dormant, so we couldn’t find anyone to blame but the poltergeists who, in the end, were remarkably successful in convincing us to camp far from their tree! However, I must add that nothing else unusual occurred during our stay and all of us had pleasant dreams that night.

According to the Laguna’s website (https://lagunalamaria.multiply.com) the “Maria” who gave her name to this place once lived a short distance from the lagoon. One day, she and her husband were invited to a dance at a nearby ranchería. Apparently the husband decided they were not going to attend the event and then announced that he was going over to the ranchería to “excuse their absence.” After the husband had left, the unfairness of what he had done tormented Maria to such an extent that she called upon the Devil himself, asking to be taken to the fiesta.

Suddenly, the Devil appeared in front of her, picked her up and whisked her high in the air. Maria screamed for help and begged to be let down on the ground. The Devil obliged by putting her in a ditch near the lagoon and placing a flat stone with four holes in it (for candles) upon her stomach. When the husband heard about all this, he told the priest at nearby Hacienda San Antonio, who organized a procession aimed at freeing the unfortunate woman from the clutches of the Devil. Praying and chanting, the crowd approached the spot where poor Maria lay, calling upon the Devil to liberate her. Immediately, the Devil complied with their wish, raising Maria high into the air until she was over the center of the lake… at which point he let her fall.

Maria’s body was never found and the lagoon became her everlasting sepulcher.

Laguna La Maria is 1.5 kilometers in diameter and a maximum of 30 meters deep. Because it is spring-fed, the water never gets stagnant. You can rent a boat and go out to the center of the lagoon to look for Maria’s bones and when you get tired of that, you can fish for tilapia, bagre or crayfish… or watch the birds crash-diving into the water for the same fish. The high, tree-covered crater wall which surrounds most of the lake is truly impressive and there are trails leading up to the top of the crater rim where you’ll find short manmade tunnels giving access to a “hidden lake” on the other side of the crater wall.

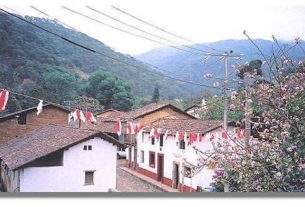

Just a few kilometers north of La Maria, lies the picturesque village of Yerbabuena, reachable by a cobblestone road in mint condition. A big sign warns you that you are at the last human outpost within the shadow of the volcano. The government tried to relocate the whole village, offering the people little cracker boxes to replace their traditional homes made of blocks hewn from volcanic rock. Most of the people of Yerbabuena are still arguing with the government about this, but have moved away, leaving the village looking like a ghost town, except for a few diehards who emphatically told us that “our village has not been evacuated.” But in many of the lovely, flower-bedecked streets where we walked, there was no living being to be seen, only a very lonely-looking, skinny mongrel that followed us wherever we went.

While the facilities at La Maria are inexpensive and a bit primitive, just down the road from the crater lake lies Hacienda San Antonio, long famous for its cheeses and gourmet coffee. In recent years, it has been transformed into an ultra-chic luxury resort with gardens reminiscent of those of Versailles, overshadowed, of course by the smoking volcano. I was told by the managers that the hacienda was purchased by Sir James Goldsmith in 1970, practically rebuilt and was a private residence for five years. Today it has 22 suites and three “Grand Suites.” The chapel was built by a Doña Clotilde in gratitude for the volcano not exploding — supposedly due to the intercession of San Antonio. Rooms at the hacienda go for close to $1,000 a night but, unlike those at La Maria, do not include spirits and poltergeists.