Mexican History

The Huichol Peyote Fiesta takes place around the end of May or the beginning of June, the start of the traditional rainy season in Mexico. The main purpose is to assure that the rain gods return to refresh the earth and nourish the newly-sown crops of beans and maize. The Huichols are located in large community centers, such as San Andres and Santa Catarina, or in scattered ranchos throughout the sierras. The Hikuri Neirra, as the Huichols call it, follows the annual peyote pilgrimage to Wirikuta, the sacred land of peyote located in the San Luis Potosi area. Traditionally, various groups of peyoteros (peyote-seekers) from various places in the Sierras set out from about October on to journey toward Real de Catorce, the jumping-off spot for the peyote hunt. When the peyoteros return, the shamans determine the time to begin the ceremony, which lasts for several days.

The Peyote Fiesta I attended at the invitation of my friend Nacho was held at Las Guayabas, deep in the valley below the plateau of San Andres in the Huichol Sierra. When we first arrived, I found myself a rather nervous outsider witness to a loud altercation between two groups of Huichols over a woman from another pueblo who had come to attend the Peyote Fiesta. It turned out that some of the Las Guayabas people thought she had no right to be there. Knowing that a Huichol was not welcome at this particular fiesta, I began to wonder about my own security. Outsiders are definitely not welcome at Huichol religious ceremonies, although the people of San Andres apparently now put on a show for tourists during Semana Santa (Holy Week, beginning on Palm Sunday and culminating with Easter). However, I was there as an invited guest. Moreover, it turned out that my friend Nacho was a much more important person on his home territory than I had previously imagined.

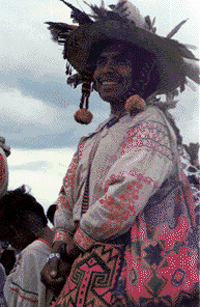

That evening, a dramatic scene took place that could have come out of a Hollywood movie. In front of a long rectangular adobe building that served as community center and seat of authority sat the shamans and elders of the pueblo. A fierce debate was going on. I scarcely recognized my friend Nacho, resplendent in his embroidered outfit and feathered sombrero as he stood up and began to disclaim in a loud voice. There was no electricity. The only light came from a large bonfire in front of the building, casting an eerie light on the intense faces of the shamans seated in their equipales, special ceremonial chairs. I managed to catch only a few Huichol words but I surmised it was about the incident earlier in the day. Whatever the issue, Nacho appeared to be in complete charge. I was thankful that Nacho and I had known each other for so many years in Ajijic and were such good friends.

The next morning, the ceremonies continued. I was sitting near the rough lean-to sun shelters where the men sat in one square area drinking great quantities of tejuino, which they would vomit up so they could drink some more. However, since there was no rowdiness, not even loud talking, I concluded that the drinking bout was part of the religious ceremony itself. Those women who were not serving tejuino, tequila, or tortillas and meat broth were sitting farther back from the center. Children played all around and were only occasionally scolded mildly for getting in the way of the ceremonies.

The peyote dance took place in front of the community center. A long line of dancers splendidly arrayed in their finest dancing attire circled in and out as they stamped their feet on the ground to raise as much dust as possible. I did not come to the Peyote Fiesta totally unversed in the ways of the Huichol, so I knew they were reminding Mother Earth to wake up and receive the coming rains. The lead dancer caught my attention. He was holding up deer antlers on his head as he wove in and out, leading the dancers through their paces. Of all the Huichols present, he was the only one wearing blue jeans. This was a particularly jarring note but Huichols can be very adaptable when necessary. Perhaps that is the secret of their survival.

At one point during the proceedings, Nacho came up and motioned to me and a few others to follow him to another ceremony at the grand calihuey of Las Guayabas. The calihuey or “god house” is the typical Huichol temple. Over a hundred years ago the Norwegian explorer and ethnographer Carl Lumholtz described the ceremonial replacing of the roof of the calihuey at Ratontita, an event which takes place at every calihuey throughout the Huichol territory once every five years. The one at Las Guayabas was very large, circular at the base, with stone walls higher than a standing person. Above that rose a very high conical-shaped thatched roof supported by long poles, each neatly bound together to form a kind of lattice work. Outside lay a large earthen square or plaza with a low adobe building off to one side. As we rounded the corner of the one building and into the square, I saw several Huichols lying flat out on the narrow stairway in front of the house apparently sleeping off the effects of the previous night’s tehuino drinking bout.

Inside the building, Nacho made me stand on an engraved stone at the edge of the fire pit while he prayed to Tatewari, the Old Fire God, seeking his blessing and — I believe — asking permission for me, a very conspicuous foreigner, to be there in the first place. At any rate nobody seemed to object to my presence, presumably because I was there at the invitation of a very influential shaman who was there to officiate at the ceremony.

Inside, I sat on a rock near the entrance, Nacho on the other side of me. Across from me on the other side of the entrance sat a Huichol magnificently attired in a brilliantly embroidered outfit, his feathered sombrero resting on his left knee. His head was propped up by his right hand and he appeared to be fast asleep. Another Huichol lay on the floor stretched out full length beside us while another one sat with his face to the wall. I was even more puzzled when I spied a rather stout Huichol lying back on a kind of long rectangular platform in the middle of the calihuey just behind the pillars supporting the thatched roof. Several children played nearby and people passed casually in and out of the calihuey. The atmosphere seemed all together too relaxed for a solemn religious ceremony. But I was not thinking like a Huichol.

Bundles of leafy green foliage hung from the high ceiling. When I asked Nacho about it, he mumbled something about it having been there from time immemorial, set in place by the gods themselves. He told me that this was the place where the Huichols originated. I had read somewhere that the traditional birthplace of the Huichols was located in Wirikuta in the general area of San Luis Potosi. However, the Huichols live in a different time and space from most of us and of course I did not question Nacho about it.

At the back of the building was a large scaffold, which Nacho said was meant to hold offerings. A few unidentifiable objects sat on top of it, while around the walls were niches apparently designed to hold offerings.

We sat quietly for awhile. Nothing happened. If you learn nothing else from the Huichols, you learn patience. Finally one of the Huichols nudged the drowsy man by the door.

Immediately he came to life, put on his feathered sombrero, and took up a position just behind one of the pillars. Others gathered forming a line just behind the fire pit. Up to this point, the stout man reclining in the center had been playing with a child on his expansive stomach. Suddenly he came to life, sat up, and picked up his muwieris (sacred arrows) and began to chant.

I heard a loud scuffling outside the door and several young Huichols came in dragging a young bull by the feet and horns. Several Huichols who appeared to be shamans assembled behind the bull. Meanwhile the stout Huichol remained seated, holding out his sacred prayer arrows, and chanting all the while. Nacho got up, took out his prayer arrows and waved them over the faces of the men. He touched his own face and the bottoms of each of his huaraches (sandals). Then he rubbed the feathers over the bull’s face.

One man, his face half-covered with a kerchief, took out a long knife and leaned over the bull’s head. Slowly, deliberately, he inserted the knife into the bull’s throat. At first I looked the other way as the bull bellowed, long drawn-out bellows that seemed to go on forever. A bull takes a long time to die. The knife was stuck into the bull’s throat several times to allow more blood to spurt out. The animal continued to convulse for a long time after the pathetic bellowing had ceased. By this time the bull’s blood had covered a good part of the stones in one part of the fire pit.

Then the thin tall older woman with the yellow peyote markings on her cheeks who had officiated at the earlier ceremony appeared. She leaned over the bull and began collecting the blood in jícaras (beaded ceremonial bowls). Then one of the shamans dipped a candle into the bowl of blood and began to walk around by the walls of the calihuey sprinkling blood in the niches and on other places on the wall. The man who had been lying on the floor when we came in directed him where to smear the blood on the wall. The cheeks of each of the shamans were also smeared with blood. The boys who had dragged in the bull were laughing, apparently amused at my presence there. But no one objected, at least not in front of me.

The ceremony ended quietly. The shaman who had been chanting simply stopped and laid down his feathered arrows. Throughout the entire proceeding he never got up or moved from his sitting or reclining position. Silently, the other participants left the calihuey. Nacho and I left a little while later.

I was impressed at how relaxed and natural the whole thing had been. Except for the plight of the bull (and here I am thinking like an outsider), I felt as if I belonged there with my Huichol friends. It had seemed more like a family affair rather than a village or communal religious sacrificial ceremony — almost like a Christian family gathering for a Bible reading and prayer. Perhaps there is really not that much difference. Perhaps we can learn more from the Huichols than we can teach them.

Part 6 of a seven part series

- Personal reminiscences of Mexico’s Huichol people I: a disappearing way of life?

- Personal reminiscences of Mexico’s Huichol people II: fiesta of medicinal plants

- Personal reminiscences of Mexico’s Huichol people III: the shaman

- Personal reminiscences of Mexico’s Huichol people IV: ritual dance

- Personal reminiscences of Mexico’s Huichol people V: journey to the sierra

- Personal reminiscences of Mexico’s Huichol people VI: Peyote Fiesta

- Personal reminiscences of Mexico’s Huichol people VII: return from the Huichol sierra