Arts of Mexico

The 1920s should not have been a flourishing period for Mexican art. The revolution had just ended. The cruelties of war and constant political upheavals had fragmented the country. And illiteracy was rampant.

Alvaro Obregon, the newly elected president, had to unify his fragile country if it was to stabilize. But how do you unify an uneducated and racially mixed people? One of his most brilliant moves was to appoint poet and educator, Jose Vasconcelos, as Minister of Education and Art.

Vasconcelos envisioned a people coming together and being educated through the arts, much as the country’s indigenous ancestors had done. Art was to belong to the people, not the elite. Artists were encouraged to produce and teach, and through both, define what it was to be Mexican.

A climate was created that opened the way for exploration and experimentation in the arts. An already unhappy student body at the Escuela Nacional de Bellas Artes went on strike to protest the rigid, classical education that the school provided. They demanded and won the right to a new director.

Ramos Martinez was the unanimous choice. His anti-academic theories breathed new life into the school. With Vasconcelos’s consent, he opened the Chimalistic Open-Air Painting School. He followed the creed of an earlier Open-Air Painting School he had established in Santa Anita. This time he opened his school with the blessing of the government, and it was sure to succeed.

Students were provided with tools, materials, meals, and rooms. A convivial atmosphere with students sharing ideas made it an ideal environment in which to create. Within months the school move to Coyoacan but continued to work in the Chimalistic vein.

The school’s original goal was to take the students from the Academy away from its classical training and to emphasize impressionistic techniques with Mexican subjects. In no time, the focus broadened. The students began adding vivid colors to their luminous palette, which was a marked departure from impressionistic subtlety.

Before long, the artists were painting their own world. It was an inevitable evolution given the encouragement they had to experiment with and master new ideas and techniques free of rigid academic norms. Here innovation and spontaneity were valued, and these artists had no intention of sticking to naturalistic work. Like their ancestors of old, they pushed for expressivity and a deeper level of meaning. The result was a unique art which set the groundwork for what was later to be called the Mexican School of Art.

It was to this hot bed of creative fermentation that Jean Charlot, a French artist, came, stayed, and made significant contributions. The year was 1921. The time was right. Charlot was part of the European vanguard whose real thrust was to reshape society. The students at the Open-Air School were also rethinking the truths of the time.

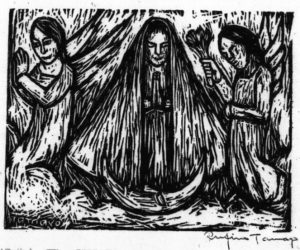

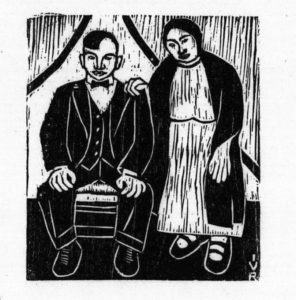

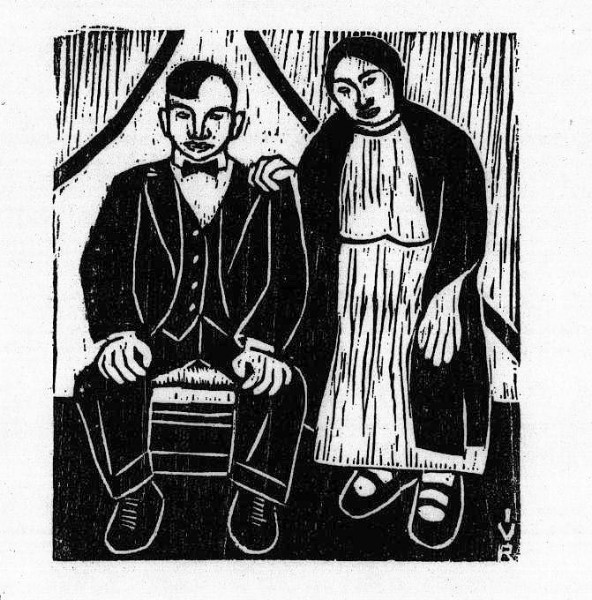

At the school Charlot met Fernando Leal who offered to share a studio with him and introduced him to other students. In this atmosphere of experimenting and new discovery, Charlot showed his new colleagues a series of woodcuts titled “Via Crucis” that he had made while serving as a soldier during World War I. The group immediately saw the potential of this medium. It was a breath of fresh air over the confined parameters of the printmaking shop at the Academia de Bellas Artes where wood had been cast aside for metal. They adopted this technique as their own special medium prizing its immediacy and expressiveness.

It was the perfect medium for the Coyoacan artists. It cost little, and its swift execution and easy printing produced instant gratification. What’s more, back at Chimalistic, the group had already been taught to carve small pieces of furniture, frames, household objects, and occasional sculptures in wood. They already had a feel for what wood could do. Charlot quickly taught them the technique, and their first prints weren’t very long in coming.

The young Mexican artists turned out woodcuts with a passion. They shared ideas and showed each other their work. They tested the limits with gratifying results. From plain backgrounds at the start, they moved on to intricate landscapes – landscapes now completely disassociated from the Impressionism that first reigned at Coyoacan.

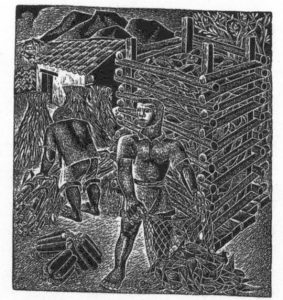

Due to cost, the artists worked long grain instead of end grain. It was a powerful creative challenge and a tribute to the scrupulous printmakers of old. Even superb engravers had to respect the grain of the wood. Many of their tools were home made. Ordinary objects like an old umbrella could give quality steel. Sharpened the right way, it could be whatever implement you needed.

In the initial group of printmakers were Fernando Leal, Gabriel Fernandez Ledesma, and Francisco Diaz de Leon. All three have left their mark in the history of Mexican printmaking. In 1922, Diaz de Leon decided to focus entirely on printmaking. By 1925, he had become a consummate graphic artist.

Many fine artists were soon to follow the original group. Among them were Emilio Garcia Cahero, Ramon Alva de la Canal, Fermin Revueltos, and Enrique A, Ugarte. These talented artists turned to woodcuts with a passion.

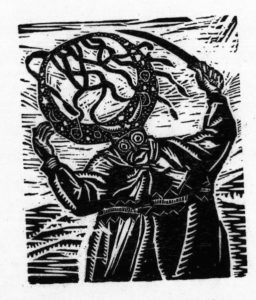

Woodcuts gradually gave way to linocuts because of linoleum’s greater ease in handling. The material didn’t splinter and could be used in any direction and give the same results. It could also accommodate hair-thin incisions and even cross-hatching, which caused endless problems in wood.

Unfortunately, very few wood or linoleum plates have survived those years. Their young creators were more involved with experimentation than posterity. Their main concern was to master the technique, give expression to a graphic language, and then let it go.

In 1924 “Ocho Lithografices (Eight Lithographs), by Jean Charlot, went on sale. That album along with several lithographs by Emilio Amero were the first fruit of the rebirth of artistic lithography. Still, it had to compete with the popularity of woodcuts. It wasn’t until1937 when Francisco Diaz de Leon founded the Book Design and Publishing Workshop at the Escuela Central de Artes Plasticas that lithography took its prominent place in Mexican art, which it has never ceded.

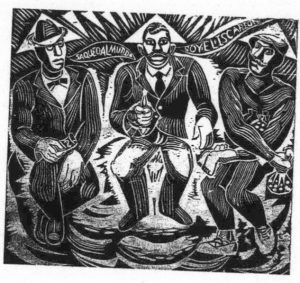

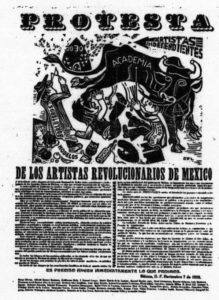

1937 was also the year that El Taller de Grafica Popular (The People’s Printmaking Workshop) made its appearance. Created by Leopoldo Mendez and aided by Jesus Arteaga, TGP became a milestone in Mexican graphic arts. Prints from the workshop spread all over the globe, and its artists won high acclaim.

The day TGP opened it doors, it was considered a vehicle for social reform. Many of the printmakers belonged to the Mexican Communist party, yet the TGP tried to stay above politics. Posters promoting leftist propaganda vied for press time with prints championing other causes. It still exists today though its founders have scattered, and it has lost its momentum.

Two other movements in the 1920s helped push the art of printmaking to the forefront of creative expression. One was the 30-30 movement named after the firearm of choice in the 1910 revolution and the number of its founding members. It dealt mostly with hot issues in contemporary art circles.

When it wrote a manifesto attacking, Emilio Portes Gil, Mexico’s newest president, it was censured. The more belligerent members were threatened with the loss of their official teaching positions, and several of its artists were sent to teach the disenfranchised in outlying villages. For years, in every corner of Mexico woodcuts and linocuts played a crucial role in conveying ideas through the medium of printmaking.

The second movement was the Estridentistas. Its aim was to reshape Mexican literature and art from the ground up. For over five years the movement used prints to grace the covers of contemporary poetry books and art reviews.

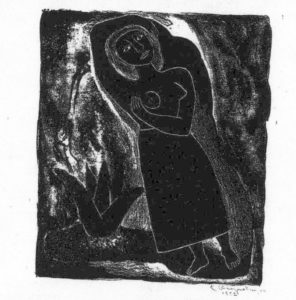

By 1947, the year that the Society of Mexican Printmakers was founded, printmaking had broadened its horizons far beyond its proletarian roots. In fact, printmaking was now considered to be the most intimate of media. Post World War II artist felt a need to reassert private values in opposition to highly politicized work. They opened the way to more subjective investigations of personal identity and myth.

Jose Luis Cuevas and Francisco Toledo are fine examples of the new sensibility. These later artists have kept alive Mexico’s reputation for excellence in the graphic arts.

Little did Charlot know what he was getting into when he showed his “Via Crucia” to eager young students at the Coyoacan Open-Air Painting School. It unleashed a creative energy that had been waiting for a medium worthy of it. It was, and still is, the perfect medium for a society in need of its expressive power.