Both the name and the coat-of-arms of San Luis Potosi recall the tremendous importance of mining to Mexico’s economy. Called Potosí in emulation of the mines of that name high in the Bolivian Andes, the city’s coat-of-arms, awarded in 1656, has its patron saint standing atop a hill in which are three mine shafts. Left of the hill are two gold ingots, and right of it, two silver ones.

Some early mining towns faded into obscurity, others became centers for ranching and commerce. Some, once abandoned, are now being resuscitated by tourism. Here are the past glories and changed fortunes of four former mining towns, a number echoing the four ingots on the coat-of-arms.

Our first stop is Charcas. Thirty kilometers west of the state capital, via highway 49 (towards Zacatecas), is the road north for Charcas, paved all the way, which emerges to join highway 57 south of Matehuala.

CHARCAS

A brief stop in Charcas will allow you to sample the town’s special flavor. This was a frontier post. First attempts to found a town were thwarted by bands of wild natives. When Charcas was successfully refounded in 1584, the war-weary victors received land for mining and cattle ranching. They constructed not only a Franciscan church (1574) but also a fort.

Today few old buildings survive but the town’s irregular streets, narrow alleyways and small plazas evoke its humble origins. The old granary is now part of a school. The eighteenth century parish church houses a statue, more than four hundred years old, of the Virgin of Charcas (fiesta every September).

North, towards Matehuala, was Mexico’s graveyard for deceased railway engines for many years. Hundreds of locomotives, reduced to bare skeletons, sat idle in the hot desert sun.

Matehuala, on highway 57, has a full range of tourist services. This is the ideal overnight stop for a trip to the ghost town of Real de Catorce, reached via Cedral to the west. Shortly after Cedral a 24-kilometer-long cobblestone road climbs up the mountain to Catorce.

REAL DE CATORCE

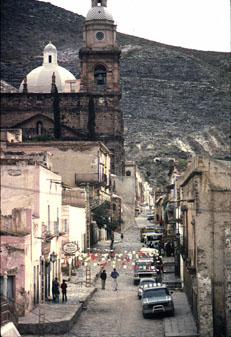

The first surprise for visitors is a single file 2,300-meter-long tunnel – the only entrance to the town from the north – a unique introduction to the many strange things awaiting you on the other side. The second surprise is how such a large place, which produced more than 3 million dollars worth of silver each year, could become a ghost town. Between 1788 and 1806, the La Purisima mine alone yielded annually more than $200,000 pesos of silver – and that was when a peso of silver was equivalent to a dollar.

The large, stone houses, often of several storeys, with tiled roofs, wooden window frames and wrought-iron work, were so well built that they have survived to tell you their tales as you wander through the steep streets, soaking up the atmosphere of one of Mexico’s most curious places.

You need time to really appreciate the former grandeur of Real de Catorce. Fortunately, there are several simple hotels and restaurants. It is well worth hiring a local guide. Jorge Quijano Leyva, who lives near the church, is outstanding. His enthusiasm for his native town will wear your feet out long before you tire of his informative commentaries.

Seek out the beautifully restored palenque. Pause in the church to examine the mesquite floor, imaginatively described in some guidebooks as comprised of a mosaic of coffin lids. The ‘ church is dedicated to Saint Francis of Assisi. The two week long fiesta in his honor, centered on October 4th, is a huge affair, attended by hundreds of returning Real de Catorce families.

In front of the church, across the small plaza of Carbón, is the former mint. This gorgeous building is now used for photographic exhibitions and for a jewelry workshop run by an enterprising Italian – why not acquire an original, handcrafted item made of locally mined silver?

From Real de Catorce, return to Matehuala and head south, past the Tropic of Cancer monument. Twenty-five minutes beyond El Huizache, where highways 57 and 80 meet, still following the -main highway to San Luis Potosi, is the side road to Guadalcázar.

GUADALCAZAR

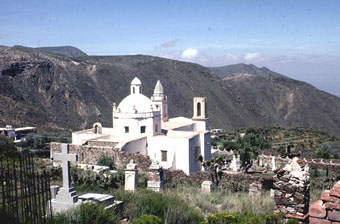

Only 18 kilometers from highway 57, through yucca-covered hills and along the side of a deep canyon, an oasis of green countryside and the towers of two main churches provide a refreshing and photogenic change.

The miners here constructed two magnificent Franciscan churches. One, near the entrance to the town, is seventeenth century. The other, eighteenth century and dedicated to San Pedro, has a glorious gilded retablo with original paintings and figures. Two blocks away is the ornate sandstone facade of the former Casa de Moneda.

The Sierra de la Mesa hills near the town inspired the local poet Manuel José Othón (1858-1906) to write some of the finest poems in the Spanish language. Othón’s’s former town house is now the Othoniano Museum, in the center of San Luis Potosi.

SAN PEDRO

Less than forty minutes from the state capital, Cerro San Pedro was the original site of San Luis Potosí and is the hill depicted on the coat-of-arms. Lacking adequate water, however, the early settlers chose to move their embryonic city to the valley floor.

In the cooler, windier climes of this ghost town, a handful of old buildings have been restored as stores and restaurants. San Pedro is full of character and should not be missed by anyone visiting San Luis Potosí.

The paved road leaves the Rio Verde highway near the village of Garita de (Los) Gómez. At the entrance to the town, explore the empty streets and peek into the abandoned houses. Today, cacti growing in the cracks and crannies of the walls outnumber the residents. Some buildings seem to be maintained by invisible guardians, reluctant to completely relinquish their hold over real estate which, in this desperately desolate terrain, cost them the best years of their youth.

Nearby, you might see miners exiting from one of the few mines still worked. Steeped in sweat – there are no mules or tramways here – they heave their heavy cargoes of ore into a small, dark strongroom before relaxing, cigarettes in hand, chatting and joking. They definitely expect to strike it rich one day.

San Pedro, founded in 1592, was abandoned about fifty years ago. The center of town, higher up the valley along a dusty, winding road, is still largely intact with an imposing parish church towering over a small, neat plaza. San Pedro comes back to life again for its main fiesta on the Sunday before June 27th. Fiesta over, the lizards, spiders and other critters crawl out from their hidey holes to reclaim their territory.

Nowhere in Mexico are the changing styles and fortunes of former gold and silver mining towns better displayed than in these four in the state of San Luis Potosí. For your next trip to Mexico, consider seeing for yourself the hidden treasures of Charcas, Real de Catorce, Guadalcázar and San Pedro.