Did You Know…?

An earlier column, “Microwaves (with a view)”, examined the scenic delights to be found by following the “Microondas” road signs that puzzle many first-time visitors. That column probably didn’t appeal to any passing historians, but another road-sign abbreviation, “EST”, could easily have been invented just for them.

EST stands for Estación. In some contexts, this would mean “season,” but in the context of road signs, it means “station”, as in Railroad Station. The sign is still commonly seen when traveling in many parts of Mexico, even though very few passenger trains now run.

Most of the country’s railroad lines were built at the end of the nineteenth century and, as a result, most railroad stations in Mexico date from around the same time. Some are wonderful architectural monuments to a (sadly) by-gone age.

Before we examine their attractions in more depth, take note that the somewhat similar sign E.S.T. also appears in many regions of Mexico. This stands for Escuela Secundaria Técnica (Technical Secondary School), a much less interesting and decidedly non-historical building, usually very close to the main highway.

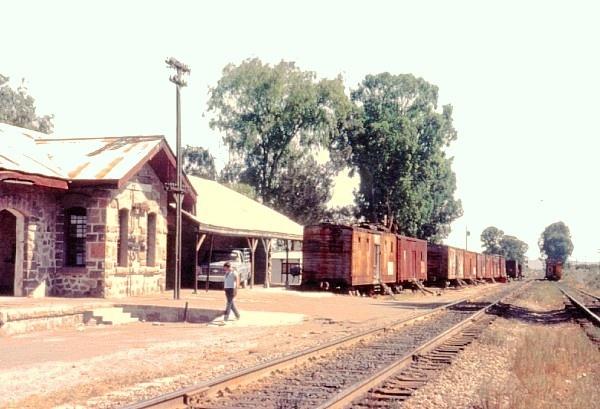

Following an “Est.” sign down a side road can turn out to be a real adventure, with plenty of historical footnotes waiting to be unearthed. The station buildings are often period pieces. Some are distinctly Norteamericano in style, looking as if they were transplanted in their entirety from the mid-west or Prairies. Others are much more European, perhaps Austrian or British. The differences, of course, are due to the sources of capital employed and the nationalities of the principal shareholders in the companies, many of them transient in nature, responsible for their construction.

While in the general vicinity of the station, look out for old railway cars and engines. In some places, box-cars have been transformed into desirable residences with flower- bedecked porches. Former engines, polished and gleaming, may have become permanent traffic islands controlling the flow of motor vehicles outside the station entrance.

Many moons ago, while on the trail of one particularly elusive “Est.”, I stumbled upon the local graveyard for all those other old engines that station masters had failed to incorporate into their landscaping plans. Dozens of these abandoned engines were sitting in splendid isolation, stripped of all potential memorabilia, along specially constructed tracks laid into the desert, near the town of Charcas, in San Luis Potosí. However, a few years later, I received a report that they had passed on into another life, having been removed as scrap.

Not far from Charcas is the small town of Vanegas, part-way along the road to Est. Catorce. Historically, this was an important railway station through which thousands of tons of silver ore passed. The silver was produced by the mining settlement of Real de Catorce, high up in the hills behind it. Today, most people visit Real de Catorce via a 2km long tunnel from the north. It is one of the most interesting ghost-towns in Mexico, and tourism has helped it enjoy a spirited revival in the past twenty years or so.

The road from Vanegas to Est. Catorce is paved as far as the authentically 1930s Est. Wadley. Now, there’s an interesting name! The letter W (pronounced doble-oo) doesn’t even exist as a letter in the Spanish alphabet which explains the virtual absence of words beginning with W in the Spanish side of any bilingual dictionary. Almost all the words you’ll find there are obvious imports from other languages, including three tourist favorites: weekend, whiskey, and wafle. Most other W words are geological terms.

My research has so far failed to prove that there was ever a Mr. Wadley in this area, even though, much further south, there really was an Englishman, Richard Honey, after whom the equally improbable Est. Honey was named. Here at Est. Wadley, perhaps the name derived from the bilingual but little known word “wad”, in its meaning as an earthy ore of manganese, the metal used to make especially hard steel alloys. Was Est. Wadley the main export route for manganese ore extracted from the foothills of the moutains which concealed Real de Catorce’s silver? A circular, unimproved track beginning and ending at Est. Wadley provided access to the mines, though some sources suggest it was mercury or antimony being mined here, not manganese!

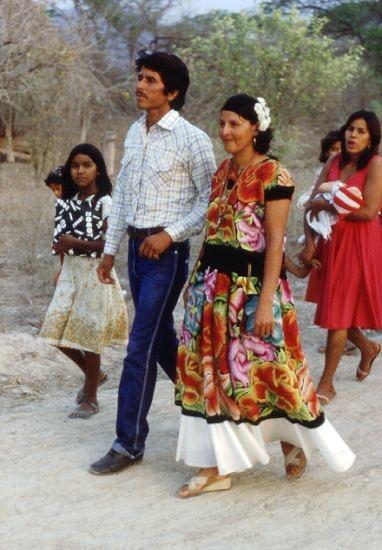

Wherever you venture, you’re bound to find something of interest if you trust your instincts and follow an Est sign. In the 1980s, in the southern state of Oaxaca, I was amazed to discover that the public shuttle-bus to the local railroad station in a small pueblo was an ox-drawn cart. Passengers, surprisingly well-attired, the women in traditional long flowing hand-embroidered dresses typical of the Tehuantepec region, and all their luggage, breathed the dust that the animals kicked up as they shuffled along.

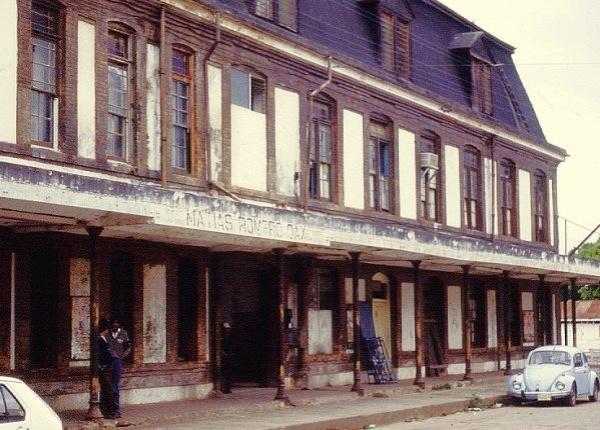

Some years earlier, in the same general region, the lovely brick-built station at Matias Romero was still proudly displaying the menu that passengers had once enjoyed in its restaurant. The menu took up an entire wall of the entrance hall and the prices on it were authentically 1930s!

Most of the railway stations of Mexico were solidly built and any that merit an Est. signpost from the main highway are almost certainly still well worth visiting. Their access roads will either be paved or at least kept in good repair, making for an easy, unlisted, but fun, side trip for your own exploration of the cultural treasures awaiting you in Mexico.