Did You Know…?

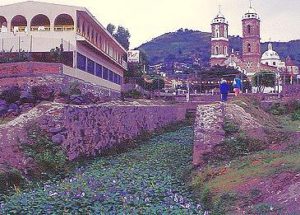

The masses of beautiful violet and yellow flowers of the water hyacinth ( Eichhornia crassipes) add an attractive splash of colour in the Lake Chapala landscape during the rainy season but the lirio as the locals call it, is a serious problem for many of their economic activities.

The hyacinth was first described in 1824, in Brazil. In 1884, a Japanese delegation at a Louisiana cotton exhibition gave specimens of the plant, which they had obtained from Venezuela, to other delegates who duly took them home to adorn their garden ponds. Unfortunately, far away from its native home, the water hyacinth then multiplied out of control. It seems that the story in the Chapala area is similar; it is likely that the water hyacinth, together with a species of carp, was brought to adorn the fish ponds of local haciendas at the eastern end of Lake Chapala also at the end of the nineteenth century. Today, the hyacinth is found in more than fifty countries on five continents.

The plant prospers on the steady supply of nutrients including excess fertilizers and soil particles washed into the lake. It does not need its roots anchored to the lake bottom, but is able to capture all necessary nutrients whilst floating on the lake surface. Its high buoyancy and mobility, which are due to air-filled tissue in its leaves and stems, allow it to be blown from one end of the lake to the other by the wind.

Lirio can multiply by clonal propagation, just as some ornamental plants do from cuttings. The hycacinth plant because its rosettes of floating leaves are held together only by delicate horizontal stems easily breaks apart into many separate pieces, each having the potential to grow into a new complete plant – as wind and water disperse fragments, so the plant spreads very rapidly.

Its speed of invasion is legendary. A Lousiana study reported that in only a single growing season, 25 plants could multiply to become about 2 million separate plants, covering up to 10,000 square metres of water surface. In enclosed areas, dense mats of dead and living organic material up to 2 metres thick can be formed.

Water hyacinth seeds can lie dormant for years, waiting for the right conditions to germinate. In the months or years following high lake levels, seeds are often left stranded on the exposed lake bed as the lake recedes. Once the water level comes back up again, these seeds germinate and grow. This may help to explain why there have been rapid infestations of water hyacinth each time the lake has recovered from low levels in recent history.

In Lake Chapala, a substantial percentage of the surface may be covered in some years; for example, an estimated 19.5 % between 1958 and 1960. By 1983, the hyacinth was back to a mere 1.7 %. In the 1993-1996 lirio plague, about 17% of the lake was covered. No-one is prepared to guess precisely how much of the lake will be occupied during the current invasion, which began in 2005.

The amount of hyacinth at any one place can vary tremendously within a few days, depending on the dominant wind directions at the time. Fishermen living at the eastern end of the lake claim that the rainy season winds, the Mexicano and the Guarechera, whip up waves which tend to destroy it, but, as we have seen, breaking it up is the first step to propagating it further! Fishermen in Jocotepec at the western end of the lake don’t worry much about the hyacinth early in the year because the February Colimote usually pushes the weed well away from their fishing areas and towards the eastern shoreline.

Masses of water hyacinth have many effects. They block canals, ditches and pipes used for agriculture, recreation or hydro-electric power, increasing the potential flood risk. Their proliferation reduces water movement, and the penetration of sunlight, and decreases the amount of dissolved oxygen in the water, endangering phytoplankton and fish stocks. The dense mats of hyacinth create ideal microhabitats for various undesirable organisms such as mosquito larvae (malarial included).

There is only one unexpected benefit of this otherwise noxious weed: its roots and leaves concentrate within them substantial amounts of polluting heavy metals which they have filtered from the lake. These heavy metals, such as mercury, iron, lead, cadmium, copper, cobalt, and arsenic are brought into the lake by the river Lerma; the Lerma collects them from the residual wastes of industries operating along its banks.

And how can it be controlled? Neither mechanical remedies such as crushing and collecting it nor chemical ones such as poisoning it have ever been shown to be very effective. Certainly, cutting it only serves to help it propagate, and usually cannot keep pace with the increased growth. In any case, even when cut, it cannot be safely fed to cattle or incinerated because of its heavy metal content. The use of chemicals may affect water quality and may have deleterious effects on fish stocks. In Lake Chapala, there seems to be a natural cycle to the cover of water hyacinth which we are powerless to alter to any significant degree with currently available methods.

The fact that all individual plants are genetically uniform (because of their cloning) may enable biologists to introduce a natural enemy of the hyacinth in order to exterminate it outside its natural South American range, just as they used a particular species of Brazilian beetle to destroy another notorious water weed, the kariba, which threatened waterways in Australasia, India and parts of Africa.

The introduction of manatees or sea-cows to control the hyacinth was successful in Guyana but elsewhere, the manatees found the hyacinth less tasty than other available plants. In Chapala, the manatee was quickly fished to extinction.

A curiosity of the water hyacinth is that, in floating plants, the flower heads or inflorescences bend downwards one or two days after flowering,, submerging themselves in the water. The significance of this characteristic is unknown but it may be to prevent pest attack.

The unfortunate mistranslation of water hyacinth as “water lily” is seen less frequently these days. The true water lily has virtually nothing in common with this champion multiplier for which we so desperately need a reliable method of birth control!