Huamantla, Tlaxcala

– As the bull charged towards me I lost my footing and fell backwards. As I leaped off behind the wooden fence, the bull began to butt against the plywood. Once, twice, three times.

I hold my breath.

Every year in this town, on the first Saturday after August 15, 20 bulls are let loose in the streets for two hours for locals to try their hand at fighting, a tradition that has lasted for fifty years in what is known as the Huamantlada, a Tlaxcatleca version of the Pamplonada (the running of the bulls) in Spain.

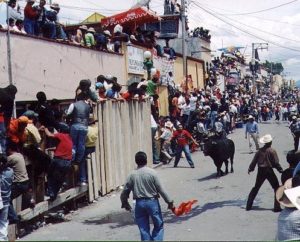

Around 11:30 in the morning, the people standing on rooftops here in Huamantla, hanging onto wooden fences and climbing the walls of the low adobe buildings begin to whistle, first one side of the street, then the other, building anxiety.

The whistles move down the street in waves, anticipating the firecrackers that will go off three times before 12 noon, the signal to let the bulls loose.

Everywhere, Huamantla feels like bull country. In the hours before the bulls are released, the streets fill with people wandering, selling cotton candy, pistachios, pulque and felt horns, red or brown, to velcro around heads and hats.

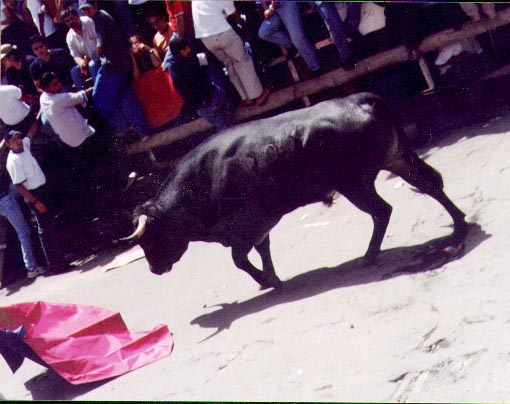

One small boy holding a tiny pink cape swirls in the street yelling “¡Toro! ¡Toro!” to a young cousin, who holds his hands to his head like horns and runs at the other child.

Teenage couples walk down the middle of the street in cowboy boots and hats, ready for the rodeo.

A young man, with a brown leather cap and a pink cape draped over his arm converses with another boy with long hair pulled back into a jazzy ponytail, boasting a black vest and a sword.

Two men with felt horns that read ” Huamantlada” climb the fence near us and wait to watch the bulls. One of them stands on the top of the fence and grabs onto the telephone wires to keep balance.

On the corners of the streets, in closed red metal boxes, the bulls await their exit patiently. I glimpse the jagged edge of a broken horn.

Posters in the bus station announced “500 kilos of fury await you in the middle of the street”. 500 kilograms?, I wonder, incredulous.

At the first whistles, we walk faster, looking for a space to squeeze into, but the wooden bleachers set up on the sidewalk are filling fast, and the owners are charging.

” 50 pesos, joven,” they tell us at one place. We keep moving. On another corner, they charge us 30 apiece, 3 dollars, to slip behind a wooden fence made of plywood and four by fours.

The people are ecstatic. Young teenage girls, couples, older women and men, families, babies and small children are waiting, climbing the make-do fences put up the day before down all the sidewalks of the town where the bulls would run, standing on the top rungs.

“Before, they didn’t charge anything to watch,” says Fermín Vázquez, a junior high school teacher from Apizaco, a nearby town, who came to the Huamantlada with his young daughter Nancy, seven years old.

It is Nancy’s first time at the bull-runs, besides the time she came when she was very little, she explains, but of course, she doesn’t remember.

The Huamantlada is, above all, a social event. People who have been coming to the bullruns for their entire lives drink beer together and reminisce about close calls with a bull’s horns.

Alejandro, who was born in Huamantla but now lives in Tlaxcala, the state capital, remembers old times.

“I went into the streets before, yes, but those were other times. I was a dumb kid,” he laughs.

Others agree the Huamantlada was different before: more dangerous, more exciting.

A year or two ago, the municipal government made a rule to allow only one bull loose on each block, and red metal gates were put up on the ends of the streets to keep the bulls in their area.

In other years, the bulls were free to run in any and all the streets on the circuit.

Alejandro explains how the bulls could catch you by surprise that way.

Once, he begins to tell us, excited, he saw a young boy who was keeping himself away from a bull in front of him when another bull came from behind, he was tossed into the air and landed square on the back of his neck on the bull’s horn.

Before, the bulls’ horns weren’t filed either.

“They said he didn’t die, but how could he not have died?” wonders Alejandro. “He landed on the back of his neck!”

When the firecrackers go off, I am standing on the fence trying to take a picture of the people running up the street and before I know it, a huge animal is charging towards me.

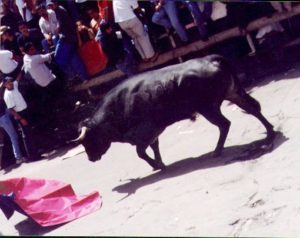

It is at least four feet tall, black, with hard hooves, horns and a tail that swirls from one side to the other. It swerves suddenly and charges back down the street, more interested by the movement of the young men waving capes and shouting on the other end of the block.

Nancy and her younger cousin push their heads through the fence to stare down the street. There is silence and calm for a second. Then the bulls come back.

Young men, wearing baseball caps or cowboy hats, jeer each other in the streets, laughing and pretending to call to the bull. When it comes charging, however, the street clears in a flash, and the boys come running full speed and climb the fences, trying to topple over to the other side.

The Huamantlada is two hours long. The bulls tire, their tongues hanging out of their open mouths, panting, but they also get angrier as time goes by. A white and gray bull joins the black one in the first few minutes, and people spray white foam over them from the rooftops above.

Farther down the block a man is punctured in the stomach and the knee. Blood pouring down his leg, he is carried by six others to the red gates at the end of the street and passed beneath.

This is what the Huamantlada is all about. To challenge danger, believe in eternity. This year, on the 50th anniversary of the event, 56 people are wounded and 1 person dies, according to official reports.

Still, the bulls carry on, as do the bull-fighters. An hour and a half after the bull-runs began, the metal fence at the end of the block falls down with a crash, and the people sitting on top disperse in a flash of dust.

The bulls come crashing towards us and there is a strong clap of thunderous horns as one of them butts against the plywood nailed against the fence again and again and again.

As I hold my breath, a young man hurls himself over the fence straight at me, then turns to drag his girlfriend across, head first.

She is hysterical.

“The bull caught a guy and slung him into the air like a fish, right next to me! Like a fish!” she cries, breathing hard.

By pure luck, the man pinned against the plywood lands between the horns and is saved. His girlfriend, on our side, faints suddenly.

And the young couple who just saved themselves leaps back across the fence once the bull is gone, ready to chase their luck further along the asphalt.