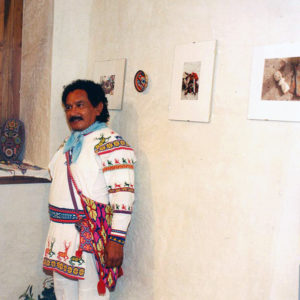

Never have I known a name to so perfectly capture the essence of a person as in the case of artisan and philosopher Kupíha’ute-Itzpapalotl. Both parts of his name mean obsidian butterfly — Kupíha’ute in the Huichol language and Itzpapalotl in the Aztec or Mexica language.

“The butterfly, or kupí, is the movement, the transformation, the continuous metamorphosis of everything. And it is also the disseminator of the seed of the culture that is kept in the flowers that represent our ancestors,” he says. The 56-year-old craftsman seems to be the very personification of his namesake, since Kupíha’ute-Itzpapalotl life is inextricably tied to the dissemination of his culture.

“Since my childhood, my passion is to discover and enjoy my roots,” says the native of Palma Sola, Veracruz, who grew up in Mexico City. As Kupíha’ute-Itzpapalotl explains, he went in search of his indigenous heritage at the age of 15, journeying to the Sierra Madre Occidental Mountains in the state of Nayarit to seek out the Huichol community where his grandmother grew up. The Huichols are an indigenous group that has traditionally resided in an area known as the Gran Nayar, located in the southern region of the Sierra Madre Occidental Mountains.

Kupíha’ute-Itzpapalotl calls the Huichol people “the seed of the native cultures all over the continent.”

After his visit to Nayarit’s Huichol community, Kupíha’ute-Itzpapalotl traveled extensively across the Americas, which afforded him the opportunity to live with and learn from a multitude of different indigenous groups. These experiences culminated in 1984, while he was teaching philosophy at a university in the Mexican state of Michoacán. It was there that he created the Nawatl philosophy, which he says was the result of almost 15 years of philosophical experience, as well as the examination of his own roots and the experience of living among more than 25 different ethnic groups from all across the Americas.

“To become Nawatl is the equivalent of overcoming voluntary servitude, civilization, education, domestication, religion and every other limitation upon oneself, to instead display one’s absolute power,” Kupíha’ute-Itzpapalotl says of his belief system.

Art is an integral part of the Nawatl philosophy, as he explains. “The way to become Nawatl is through the ritual art that is conceived through a ritual journey into one’s self, unveiling the original source of being one’s self.”

It was in 1992, while living in San Blas, Nayarit, that he began focusing on the artistic creation that is such an essential part of the Nawatl philosophy. There in San Blas, the philosopher started making beaded handicrafts inspired by the ritual art of the Huichols.

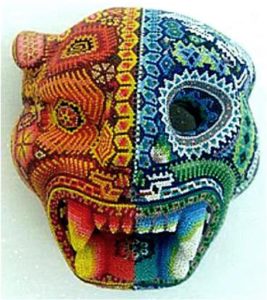

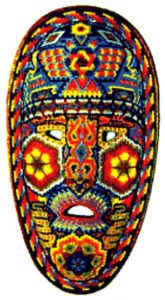

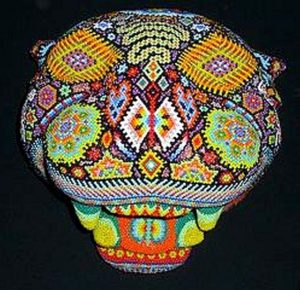

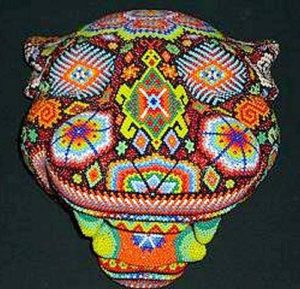

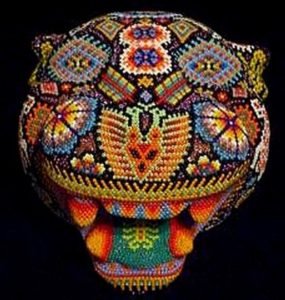

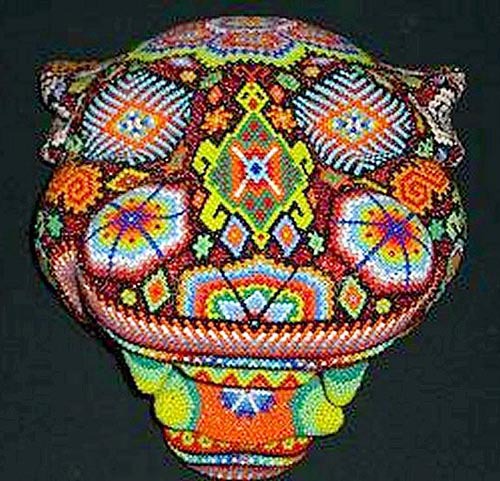

When making his creations, Kupíha’ute-Itzpapalotl starts off with a carved piece of wood and applies a layer of pine pitch to it, which acts as an adhesive. Then, one-by-one, he affixes glass seed beads to the piece, using a maguey thorn or a pick made of abalone to press them into the pine pitch.

“I use the thorn of maguey or the pick of abalone to have more precision — no matter the time that it takes,” explains the artisan. His technique produces intricate pieces that are covered with vibrant designs.

“If you compare my style of beading with the Huichol, I do not repeat two rows of the same color,” he says. “I am trying always to achieve the finest delineation of the designs, the highest contrast possible and the sharpest figures to impact your unconsciousness as (strongly) as possible.”

Kupíha’ute-Itzpapalotl pieces are fraught with symbolism, as each of their beaded depictions signifies a more profound meaning. For example, his work entitled “The Trance of Passage” is comprised of a 6 x 7 ¾ inch wooden puma head covered with a multitude of designs, including a peyote cactus, butterflies, a deer, a serpent, a two-headed eagle, sea turtles, a double spiral and a scorpion. According to Kupíha’ute-Itzpapalotl, the wooden puma head itself symbolizes the hunting spirit of the aboriginal shamans. The peyote cactus represents the place of the soul, while the butterflies signify metamorphosis. The deer is a symbol for the soul that is guiding the way to wisdom — the body wisdom or unconsciousness that is represented by the serpent and the mind wisdom that is depicted with the two-headed eagle. In the center of the eagle is a deer head, which signifies the shamanic soul that conveys wisdom through ritual chants. The sea turtles represent the ancient ancestors, the double spiral is the symbol of energy and the scorpion signifies wisdom.

Each of the artisan’s pieces is created without a predetermined pattern, which is a fundamental aspect of Nawatl ritual art. Aside from his own work, Kupíha’ute-Itzpapalotl points to the Tastoan masks created by Prudencio Guzmán in Jalisco and the alebrijes crafted by artisans in Oaxaca as other examples of Nawatl art.

“The essence of the Nawatl philosophical art is that it is created completely, absolutely freehand… with no sketch or model or copy whatsoever,” Kupíha’ute-Itzpapalotl explains. “So the process of creation implies a ritual journey inside oneself through which one revokes (and) collects the archetypical symbols and the legends of one’s ancestors.”

For Kupíha’ute-Itzpapalotl, each creation process allows him to discover something new inside himself. He describes it as a “rebirth” or a “metamorphic transformation” towards himself.

And at the same time that Nawatl art allows the creator to connect with himself and his ancestors, it also provides a link between him and the viewer.

“The Nawatl art is creating archetypes, in the Jungian sense, awakening unconsciously the common roots of the artist and the viewer,” Kupíha’ute-Itzpapalotl says. “It is a process of psychological transference.”

It is in this way that Nawatl art keeps the meaning of ritual art intact, he explains, since it then acts as a ritual offering. He likens Nawatl art to a mirror, in which “the artist and the viewer meet to awaken and enjoy their common roots.”

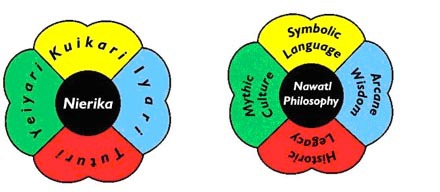

This mirror is at the core of what he calls the Nawatl Topological Scheme, which is a wheel that is divided into four different dimensions, with a fifth at its center that is produced by the interrelation of the others.

“In the pre-colonial world, there is no the verb ‘to be,’ but only the verb ‘to stay,'” Kupíha’ute-Itzpapalotl notes. “Since everything (and) everyone is mortal by definition, then there is not ontology, but topology. One is defined by its place, not by being.”

The Nawatl Topological Scheme’s four dimensions are the iyari (heart) or arcane wisdom; the kwikari (chant) or symbolic language, the yeiyari (pathway) or mythic culture and the tuturi (flower) or historic experience. The fifth dimension is the nierika (mirror), which signifies the Nawatl philosophy, ritual art, the surrounding world and one’s own life.

As Kupíha’ute-Itzpapalotl explains, the journey of creation starts in the depths of one’s iyari or heart, where one’s arcane wisdom dwells. It then progresses to the kwikari or shamanic chants, through which one expresses his symbolic language and develops his yeiyari or pathway that allows him to add to the tapestry of his mythic culture. He breathes the scent of the tuturi or flowers and is inspired by his ancestors’ historic legacy to continue living as the most beautiful and powerful nierika and thus, accomplishes his aim of becoming the most fertile ancestor possible upon death. In this way, he triggers the journey of creation to begin once again, which ensures the everlasting movement of the cosmos.

And ritual art places the artisan in the midst of this cosmos. “Ritual art is an invitation to acknowledge oneself from the Nawatl perspective, since it is a calling to dwell in the center of the cosmos, from where one has the perspective of the four dimensions that shape every moment,” he says.

For the artist, the connection to Nawatl ritual art grows stronger with time, as each creation provides him with a deeper sense of self. “The becoming of what one is develops with the exercise of the activity,” Kupíha’ute-Itzpapalotl says. “It is a process with no end.”

Thus, what sets Nawatl handicrafts apart is that they are not merchandise, but truly ritual art. Yet, not all viewers understand this concept when they are looking at a piece of Nawatl art.

“Although the Nawatl art is a mirror, it is not magic,” he notes. He explains that when an ignorant person is placed in front of the mirror, ignorance is unfortunately reflected back. “You need talent in the viewer to acknowledge the talent of the artist,” the philosopher says.

For Kupíha’ute-Itzpapalotl, it is extremely frustrating to hear people comment that it must be a tedious or time-consuming process for him to create his art. “Time for me is not a criterion to value my art, since, for me, the artistic activity is the same as to play an instrument or to have carnal relation,” he notes.

The general public’s widespread ignorance surrounding ritual handicrafts has caused a discouraging situation for the artisans who create them. For example, Kupíha’ute-Itzpapalotl says that his two children, 24-year-old Tonakatekutli-Tepeyolotl and 25-year-old Xochitl-Yollitztli, are skilled in the techniques of Nawatl art, but are not currently focused on creating it.

“I am longing for the time (when) they dedicate (themselves) full-time to the most fulfilling activity in the entire cosmos, but it is very difficult to live out of the ritual artistic activity,” Kupíha’ute-Itzpapalotl says.

The Obsidian Butterfly himself has at times struggled in his attempts to foster the growth of ritual art. One of the biggest letdowns for him was the decline of his organization, the Wichol Cultural Community, which was founded in 1992 and achieved non-profit status in 1999. The focus of the group is to disseminate ritual art without the use of a middleman, which means the handicrafts are not sold for a hefty profit and thus, retain their significance as ritual offerings.

“This was the greatest chance to offer our artifacts, not as merchandise, but as ritual offerings,” recounts Kupíha’ute-Itzpapalotl, who created the organization with some other artisans in San Blas. “We were receiving donations deductible from taxes and feeding back the people with an art piece of the same value of the donation received.”

However, the group experienced difficulties in its first year as a non-profit, as the government decided to revoke its status and require the payment of taxes. The other problem was that many members were unable to comply with the sole condition of the organization, which is to abstain from drinking alcohol.

“Before 1999, we were 500 persons together,” Kupíha’ute-Itzpapalotl recalls. “After 2000, it was me and my daughter.”

Yet, despite this disappointment, Kupíha’ute-Itzpapalotl continues to persevere with his mission from his current home in Ensenada, Baja California. He is exhibiting his work there in Ensenada and has previously done so in San Blas, as well as in Loreto, Baja California Sur; Ensenada, Baja California; and Sondrio, Italy, but is currently focusing his efforts on the Internet as a tool of dissemination. “I want to keep on doing all of my exhibitions on the Web,” he says. “Otherwise, I should depend on the kindness of the intermediaries, which is shameful.”

Like his winged namesake, Kupíha’ute-Itzpapalotl is steadfastly committed to the diffusion of Nawatl culture across the land.

“The present ritual art is the new way to spread the seed of the Nawatl perspective,” he says. ” Nawatl is the name of humankind before the colonization of Nawatlan (the Americas). So all the peoples, all the cultures have a common ground, a common way to perceive and express the cosmos: the Nawatl perspective.”