Exploring Mexico’s Artists and Artisans

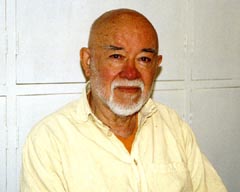

“I am from Mexico, but it is like (being) from another country that no longer exists,” says famed potter Juan Jorge Wilmot Mason.

Born in Monterrey 77 years ago, Wilmot eventually made his way to his long-time residence of Tonalá in the late 1950s. He says that Tonalá had far fewer inhabitants back then and that “everything was very simple.” Indeed, Tonalá’s population has risen considerably, swelling from 11,486 in 1950 to 337,149 in 2000. And as the passage of time has resulted in an increase in Tonalá’s population, it has brought other changes to this municipality and Mexico as a whole.

“The Mexico of today is no longer the Mexico of 50 years ago,” Wilmot laments, as we sit together in his modest abode in Tonalá. Sparsely furnished, the main room’s principal point of interest is Wilmot’s collection of books. He pulls various volumes off the shelves to illustrate his points, as he delves into the country of his youth and contrasts it with the Mexico of present day.

At one point, Wilmot sets down a massive, hardcover book about orchids in front of me and opens to a page illustrated with photos taken in Chiapas of sumptuous foliage and crystalline rivers.

“In those times, I went to the ruins of Bonampak (in Chiapas)… and the river Lacan-há was like this,” he says, pointing to the photographs. “I was in Bonampak, but with the man who discovered it, Mr. Charles Frey,” Wilmot explains. “But like the song says, ‘those were the days, my friend.'”

He also recounts a trip in 1957 to Isla Mujeres, where he traveled with a renowned architect from Switzerland. “There were no hotels,” he notes, laughing about how they parked the car under a coconut tree, only to have the coconuts fall and smash the windshield. “We had to sleep in the sand; it was very enjoyable, very tranquil. And the food was marvelously delicious and very cheap,” Wilmot notes. “But that was the way it was in the past,” he says, lamenting that the Isla Mujeres that he remembers no longer exists. “It has already come to an end,” he opines.

In contrast to the days of his youth, contemporary Mexico and the world as a whole are caught up in a dark era, Wilmot says. “We are in a bad period. In India, according to their way of thinking, there are kalpas that last I don’t know how many thousands of years. And right now we are in the kalpa of conflicts.”

One change in Mexico that makes Wilmot especially sad is the steady disappearance of those natural treasures that he holds so dear. “It is a truly sad thing because they are accumulating garbage,” he notes. “There are things in here that I saw first-hand,” he says, pointing to the book about orchids. “But all of these invasions that we have by Wal-Mart and McDonald’s and other horrors…” he comments, trailing off into silence.

Despite his fondness for the Mexico of yore, however, Wilmot is acutely focused on the present. “For me, ‘remembering is living’ is not the way it is,” he says.

Thus, Wilmot is reticent to speak of all his many accomplishments in pottery, a career from which he retired eight years ago. This internationally renowned craftsman has been honored with various accolades, including the Premio Nacional en Artes y Tradiciones (National Prize in Arts and Traditions) and an award by the Fomento Cultural Banamex.

When asked what he thinks of his body of work, Wilmot responds that he actually doesn’t think about it at all. “I consider myself among certain people, yes, keep my fingers crossed,” he laughs. “(I had) luck,” he adds. “Luck, on one hand, we could say genetically. And then the luck of seeing a world that didn’t have all of this awful contamination.”

Wilmot’s interest in art began when he was a boy, leading to studies in Germany’s Black Forest and Basilea, Switzerland. Eventually, he set up his workshop in Tonalá, where he created decorative and utilitarian ceramic pieces, as well as work made of blown glass, iron and sheet metal.

“I dedicated almost 40 years of morning, day and night to it – it was an obsession,” he says of his work as an artisan. “It was also very satisfactory because the environment, the people and the circumstances, everything favored this.”

Wilmot started off with traditional Mexican pottery techniques, like barro bruñido, but eventually gained international recognition by introducing the ancient Chinese art of stoneware to Tonalá. It was Wilmot and the American craftsman Ken Edwards who installed the first stoneware kiln in Tonalá, according to Prudencio Guzmán Rodríguez, who is in charge of the Museo Nacional de la Cerámica (National Ceramic Museum) located in Tonalá.

While talking about his work as a potter, Wilmot pulls out a magazine with images of Chinese ceramics in it. “This is what I wanted to do and it happened,” comments Wilmot, pointing to the photos of the ancient blue stoneware. “It is one of the classic Chinese techniques,” he says, explaining that this type of pottery is crafted of semi porcelain and glazes. “The problem of these glazes is achieving these types of colors without cobalt,” he says, pointing to the glossy shades of blue gleaming in the magazine photos. “I was absolutely sure that it could be done, but it took me 30 years. And nobody cared. But it doesn’t matter because I was the one who wanted to do it, (so) I was the one with satisfaction.”

Yet, after all his years immersed in the world of pottery, Wilmot no longer considers it a focal point of his life. “I had an immense collection of almost 4,000 objects related to ceramics, handicrafts and all of that. But everything came to an end. And my interest also ended. It was like a circle that closed, completed,” he says.

Although Wilmot still believes that art is an integral part of the world, he is more interested these days in discussing the breadmaking that goes on in his home. “Right now, I’m dedicating myself to trying to… teach people to make bread,” he says. “Since we live in a world of lies, then this is something that is in earnest.”

A gracious host, Wilmot brews up some coffee and sets it out on the table with the most recent batch of bread. When I ask Wilmot if he was the baker, he responds with a laugh. “Not me. It’s like this – I am the instigator,” he explains.

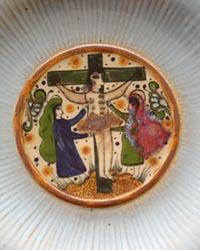

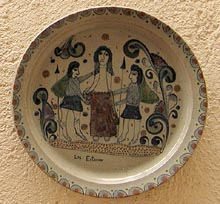

Instigator is a role that Wilmot has long fulfilled with seeming ease. Many artisans worked with him during the years that he ran his pottery workshop, with craftsmen like Salvador Vásquez going on to become acclaimed artists in their own right. There is actually a series of plates signed by both Wilmot and Vásquez currently on display at Tonalá’s National Ceramic Museum, which is located in Wilmot’s former house. The plates depict the Stations of the Cross with naïf-style scenes that show Jesus Christ’s journey to his crucifixion and eventual death on the cross. The scenes are illustrated with shades of blues and greens, with some shimmering touches of golden hues that suggest the plates were fired at high temperatures.

Even though Wilmot is no longer actively working as a potter, he continues to serve as an inspiration for artisans like Guzmán of the National Ceramic Museum, who still recalls his first encounter with Wilmot years ago. Guzmán, at the age of 18, was putting on an exhibit showcasing local artists and invited Wilmot to participate. The potter declined to take part in the event, explaining that it wouldn’t make any sense to do so because he didn’t consider himself an artisan.

Over the years, Guzmán has struck up a friendship with Wilmot and treasures the many conversations that they have had. “Jorge talks about foundations and having to change the world and having to make an effort,” Guzmán says. “Every time I talk with Jorge, it makes an impact on me.”

And although Wilmot makes light of the artistic legacy that he will leave behind, saying that it would be better for people not to remember him at all, it is obvious that he has served as a lasting inspiration to others in the Mexican art world.

“Jorge has influenced me greatly. He has really made an impact on me,” Guzmán comments. He likens Wilmot to a light guiding others on the difficult path that is life.

As for Wilmot, he says, “when I was working, I never thought of it as creating a piece of art. I was doing what I wanted to do and what I could do and I organized other people to do it.”

“T.S. Elliot said it and it is very true, but even more so now, ‘ridiculous the waste sad time stretching before and after.’ In the interval between, one does what he can.”

Photos by Kinich Ramirez © Kinich Ramirez 2006