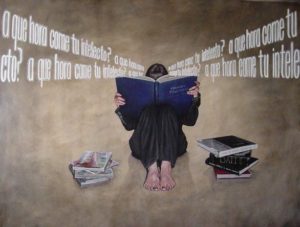

Lorena Rodríguez is shattering stereotypes about Mexican women one brushstroke at a time.

“When I first started exhibiting outside of Mexico, I realized that a lot of people have this image of a Latin American woman as subdued, ignorant and in the shadow of men,” says the 34-year-old artist from Monterrey, Nuevo León. “They were surprised that the women in my paintings are strong and modern.”

Indeed, Rodríguez’s works introduce viewers to multidimensional, female characters who inhabit Mexico’s contemporary landscape. Her paintings explore the many layers that comprise these women and the society in which they live.

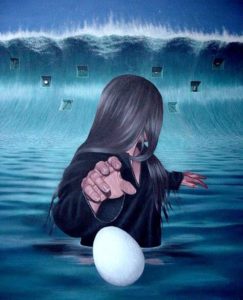

For instance, a piece entitled La Ola (The Wave) depicts a woman wading through water, one hand reaching towards an egg floating within arm’s length and her head turned towards a wave that towers menacingly in the background, poised to crash right down on her. Contained in the wave are eight different shadow boxes, each with a different object inside.

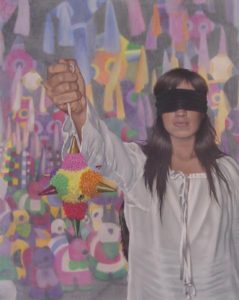

“The wave speaks about how everyday things overwhelm us — money, time, old age, work, family, marriage, society – while we are walking, as if through water, trying to reach our goals,” Rodríguez explains, adding that “the egg is a symbol of rebirth.” In another painting, we see a blindfolded woman standing in what looks to be a storeroom filled with piñatas. From her outstretched hand dangles one of these papier-mâché creations that are typically filled with candy and still used at children’s parties in Mexico. However, the piñata in this painting is filled with something other than the usual treats.

“In the painting Piñata, nails come out when it breaks,” Rodríguez notes. “Because in life, the outcomes are not always what we expect.”

Yet, despite this uncertainty, Rodríguez’s characters persevere, much like the artist herself.

“I paint because I love what I do, not because I want to be an international superstar. This way, I keep my artistic freedom and I don’t compromise my art,” the painter says. “But I cannot deny that I would like women to have a better place in art worldwide. I mean, for every Frida Kahlo, there are a hundred or a thousand known male artists.”

Rodríguez wishes more females were on the other side of the canvas, actually creating the art instead of serving merely as the subjects of it.

“I would like women to have more of a protagonist’s role in art and less a thematic one,” the painter explains. “If I can help make this happen, I will. I mean even if it is just helping to motivate other female artists, sowing the seed of art in little girls, opening the path for others, etc.”

Rodríguez has had just such a motivating artistic force in her life from the time she was born – her mother, who is painter and art teacher Elsa Ayala. One of Rodríguez’s earliest memories related to art is being in a plaza where her mother and others would sit and practice painting portraits. She and her sister would wander among the easels, where they would have a chance to study the paintings and sometimes even pose for portraits. And today, Ayala continues to be one of her daughter’s most ardent backers.

“She has always supported me, in many ways,” Rodríguez says of her mother, pointing out that she has supplied her with everything from artistic materials to opinions about her paintings. “But the most important thing is that she has never been against my artistic call, since she is also an artist.”

In fact, it was Ayala who suggested that her daughter study art when it was time to attend university. However, Rodríguez’s father convinced her to attend his alma mater, Instituto Tecnológico y de Estudios Superiores de Monterrey, where she majored in marketing. It was at this same university, though, that Rodríguez had her first individual art show. It was a pivotal event for the painter, as she explains.

“Thanks to my mother, I have been [immersed] in art since I was born, so I couldn’t point to a specific moment in which I started in it. [But] if I had to choose one moment, it would be when I had my first solo exhibition at the university in 1992, when I was 19 years old,” Rodríguez says. “After my first solo exhibition, I gradually became increasingly involved in the artistic environment.”

And thus, the transition from would-be marketing executive to full-time artist was a smooth one.

“It was a decision I didn’t even have to make. It happened by itself,” Rodríguez notes.

In the decade and a half since that first solo show, Rodríguez has participated in both individual and group exhibitions throughout Mexico, as well as in Argentina, Canada, Hong Kong, Macau, England, Italy, Spain and the United States.

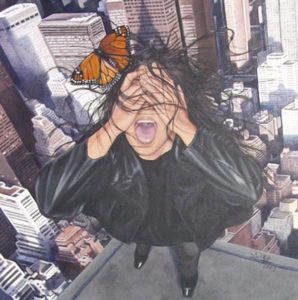

Two of Rodríguez’s trips to the United States inspired her paintings Metamorfosis (Metamorphosis) and ¿Tus vacaciones, mi victoria? (Your vacation, my victory?).

Metamorfosis focuses on a woman standing on the roof of a building, with a sea of skyscrapers forming an urban backdrop behind her – one of them marked by the distinct shadow of the Empire State Building. The woman’s head is flung back, her mouth open, her hands over her eyes, and her hair in disarray as if a strong wind is blowing. In contrast to the concrete cityscape that surrounds her, there is a colorful Monarch butterfly fluttering just above the woman’s face.

“I made Metamorfosis when I went to exhibit for the first time in New York,” Rodríguez recounts. “It was soon after 9/11 and so the city was undergoing a change and so was I, in starting my international career.”

Rodríguez’s metamorphosis is symbolized by the Monarch butterfly, whose path she traced from Canada to Mexico.

“On that (same) occasion, I went looking to exhibit in Canada… I followed the route that the Monarch butterflies take every year to hibernate. They come from Canada, pass through the U.S. and arrive in Michoacán, Mexico to pass the winter,” the artist says, noting that the trip was a transformative experience. “That is why I have a butterfly chrysalis in my throat, because it is a change that came from within.”

Rodríguez’s other New York-influenced painting, ¿Tus vacaciones, mi victoria?, again features a female character in the foreground with the city hulking behind her. This time, the woman is standing on the ground, with a male companion next to her. He is holding a video camera, while she is clutching a Mexican flag that obstructs her face. Standing in the middle of Manhattan’s famed Times Square, the pair is dwarfed by the massive buildings aglow with garish billboards and gleaming lights.

“It is about my second show in New York when my boyfriend accompanied me. My family and my boyfriend were going on vacation… and I was going with my small victory,” Rodríguez says of the painting, which has an alternate title of “Times Square.” “But you realize that with New York being such a cultural city, you are only a grain of sand among so many fine artists. And that is why the word victory is followed by a question mark.”

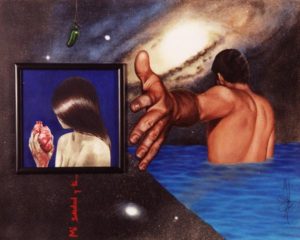

Like the aforementioned painting, many of Rodríguez’s pieces seem to explore universal themes that are informed by the artist’s own experiences.

“One never knows from where the next inspiration will spring forth… but I definitely believe that every piece of work is biographical, even the most abstract one,” Rodríguez explains. “The artist always leaves something from himself in his work.”

In Rodríguez’s pieces, the most obvious references to her are the female characters themselves, as most bear a striking resemblance to the artist. Originally, her model was a friend who looks so much like her that they have often been mistaken for sisters. Eventually, the friend became pregnant three times in a row, so Rodríguez started acting as her own model and has continued to do so ever since.

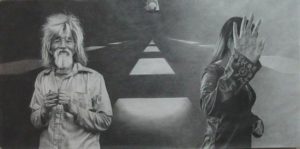

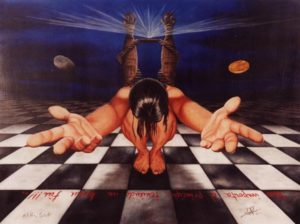

In order to avoid that the paintings appear too personal, though, the artist often hides the faces that appear in her work, instead focusing on the characters’ hands.

“Maybe the reason I usually include hands as a symbol is because I work with my hands,” Rodríguez notes. “Besides, it seems to me that hands say a lot about oneself – if they are hands worn by work, manicured hands, if they are thin or strong, etc….”

Rodríguez says that the hands reveal much about her characters, perhaps even more than the faces themselves would. In addition, by concealing the subject’s face, it allows the artist to portray the character as an everywoman.

“By avoiding faces, (the painting) becomes a reflection of Latin American women in general, instead of a portrait,” she explains.

And in giving voice to Latin American women, Rodríguez’s paintings inevitably examine the cultural traditions that are a natural extension of both the artist herself and her subjects.

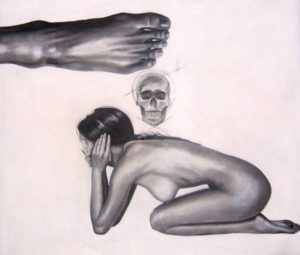

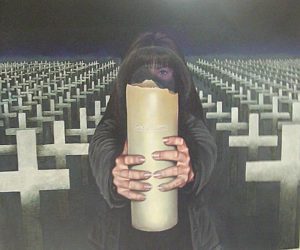

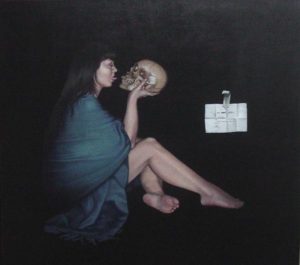

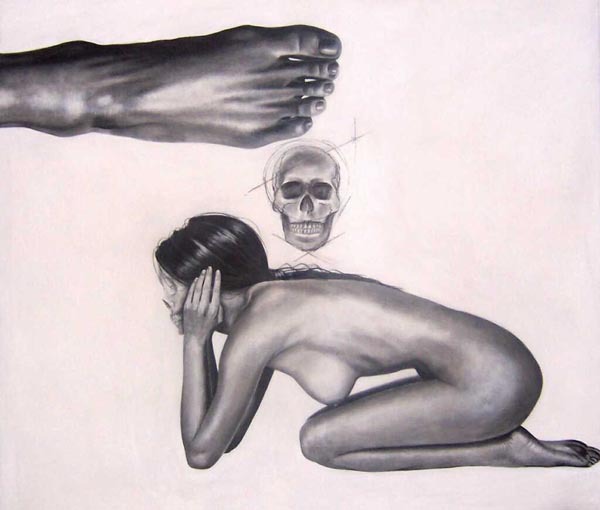

For example, skulls as a symbol of death are a recurring theme in Rodríguez’s work. In one piece, entitled Con Una Pata Allá (With One Foot Over There), a nude woman is shown crouching underneath a skull and a large foot. The woman has a sleek, feminine form and shiny black hair, but her face is eerily devoid of flesh.

Con Una Pata Allá speaks of the balance between life and death (and) of the fragility that is life,” Rodríguez says. “We should live intensely because the only thing we can be sure of is that someday we are going to die. We always have one foot on the other side.”

“The idea of death spins around in my head quite often,” the artist notes. “I have a sort of fixation with it – maybe because of the culture to which I belong. We view death with humor and maybe we are the only country that does.”

These traditional concepts gain a new context in Rodríguez’s paintings, however, as she is also adept at capturing the modernity inherent in present-day Mexican society. Her work portrays a multifaceted culture in which traditions coexist with technology. “I want people to see the other part of Mexico – a modern country with technology,” she says. “I am passionate about many things, such as science, technology, astronomy, etc.,” the artist adds. “Almost any theme interests me and all of that is reflected in some way in my work.”

Thus, Rodríguez’s paintings are just as multilayered as the artist herself, as her very essence is intertwined with the brushstrokes that she leaves behind on the canvas.

“Art reflects a world’s history, a country’s history, a region’s or a city’s history,” Rodríguez says. “And most of all, it reflects an artist’s history.”