Every so often, an event or circumstance occurs which changes the way we think of ourselves, or our place in the universe. Today was a day like that.

Late yesterday, a guest of my neighbor learned of an Indigenous celebration to be held today, high in the mountains. If I wanted to join her, horses and a guide would be waiting. The price and time were agreed upon. That was all we knew.

The journey

At 6:00 in the morning, the horses cantered up to our door. My mount was a young stallion, rebellious and frisky. This was my second time – ever – on a horse. Jesús, our guide, held my horse’s lead to his saddle, and Johanna, a more experienced rider than I, brought up the rear.

Within two blocks, we began climbing the mountain. It was dark. Very dark. Dawn does not come before 7:30 AM in Ajijic at this time of year, and the sky was cloudy, with occasional drizzle.

Our ascent was close to perpendicular. At first the path was normal: space to walk two abreast, if the two were skinny. Very soon, the path changed to invisible.

Jesús and the horses seemed to sense a path. Johanna and I could only trust them. Brush and trees overhung the way with wet, drippy foliage. We would move a hundred feet, and Jesús would chop some branches to clear a way. The path began to include scissoring, hairpin turns. A ravine dropped off on our right. In the brush, we could hear a waterfall gushing.

Johanna would call, “Wait! I can’t see Sheila’s white coat.” I would respond, “Lean onto your horse’s neck as you come around the curve; there’s a low hanging hat-shredder.” A half dozen times, Jesús paused to let the horses rest. Their panting told of the altitude, and their nervousness.

The way was muddy, and the horses slipped a lot. Jesús was taciturn, confident, stoic.

There was a sense of wonder, of other-worldliness about the silence, the lack of stars and light, the eerie sounds of nature that are normally filtered by life in a city or village. When suddenly we reached the top of the mountain, I had to hold my breath not to gasp.

The setting

There, around the final curve, was a white plastic tent village. Hundreds of Indians live here in tents, many of them all year round. Others had traveled for miles to participate in the ceremony. One or two person tents, mostly the domed variety, were everywhere. Every tent was encased with a plastic cover, for this is the rainy season. And last night there had been a thunderstorm.

The ground was rocky, muddy, slanted. Few people were stirring. We dismounted, and shivered. We wore layers, and hats, but we were wet, and we were high up a mountain. I don’t know the altitude, but Ajijic is 5,000 feet, and we had traveled an hour higher on horseback. We stood around and waited.

Within the hour, people began to stir. Sleepy, cold, damp, they appeared out of their plastic homes. Some people wore western garb; others wore blankets or ponchos and nothing more. Cigarettes glowed in the morning dawn. People walked the path to the W.C.s, following painted signs. The facilities held toilet seats over a pit, and sawdust to clean with.

Three gringos had spent the night in (separate) backpacking tents. Peter and James are students; Jon is a transplanted American who is half Indian himself. We formed a loose alliance; just speaking English can bring camaraderie in an alien culture.

Jesús, our guide, asked if he could leave and go back to Ajijic for about 3 hours: he had work to do. I agreed, provided he would come back for us. He left.

About 9:00, we wandered to the “kitchen,” a large lean-to with two llong plank tables outside. Everyone lined up, and the women inside began to serve a hot meal. Rice and beans or lentils were dished into a wooden bowl or cup, whichever was handy. Stove-boiled coffee, very sweetened, appeared in chipped mugs. Plastic or stainless spoons were on the counter. We took a serving, and climbed onto the bench at the table.

Tortillas (of course) appeared, and appeared, and appeared – and disappeared as quickly as they came. Johanna and I were the only women at a table with mostly adolescent males, and the testosterone was palpable. The usual clowns spoke louder and louder, and the elders would call to them to be quiet. But their hormones pushed them again, and again the request to ” Callanse.”

When we finished eating, we carried our dishes behind the kitchen, where everyone washed his/her own utensils outside with a brush made of twigs.

The celebration

We trod carefully toward the ceremonial circle – as close as observers are allowed to go.

Within the large circle, only approved dancers and warriors are allowed.

To prepare for today, they have fasted from food and drink for four days, although the use of mescaline is encouraged. This morning, the celebrants shared a “sweat:” a cleansing steam bath.

Today’s celebration is La Danza del Sol : the Dance of the Sun. It is a ritual event, dating back at least 500 years. A heritage from the Lakota Indians, it is reputed to have arrived from ancestor Lakota in what is now the USA. Its purpose is to thank the Great Spirit for another year of life.

We were told that if we arrived early, we could witness a sacrifice: selected men pierce their chests with wooden spears, and are hung by the spears from a tree (think “A Man Called Horse”). That happened today, but not for outsiders to witness.

We observed from our prescribed distance. Jon WhiteCloud, our American Indian companion who had studied with the Lakota, helped us understand the ceremony.

When the drums started, the dancers entered the circle, blessing themselves first from a smudge pot held by one of the spirit leaders. Men led the chain of dancers, bare to the waist, and wearing loincloths in primary colors, often with a ground length panel. Round their heads were colored bands with two feathers in each. Women followed. Their ceremonial clothes were yellow or red or white, with beaded pendants and headbands and belts. Twice the dancers circled the area, always moving first to the left, in the direction the earth turns.

I asked a gatekeeper if all the participants were Lakota, and he answered yes. I swallowed my surprise, for there were blondes with blue eyes, and red-heads with curls, and women with peaches-and-cream complexion, as well as dancers with shiny black hair and sienna skin.

The drum beat methodically, representing Grandfather’s Heart. Its rhythm changed little, but the vocal chant varied with each dance. Prayers of thanks were raised to Grandfather, to Mother Earth, to the Sun, to other spirits. As a chant to the hawk spirit began, two black hawks suddenly swooped over the circle, as if on cue, and bird cries rose from the singers.

Outside the circle but adjoining it, a swelling group of other Indians danced. These are the Servers, who apprentice for two years before being allowed to join the circle. As servers, they haul water to the campsite, cut trees and gather firewood, cook, clean, and provide all the support services.

This first dance continued for an hour, and ended as it began, with each participant passing before an elder for a blessing from the smudge pot. Then the warriors and dancers secluded themselves again, and medicine pipes were passed around for anyone to smoke.

Ritual

The mood of the camp had changed dramatically from the casual, bantering atmosphere at dawn. During the dance, everyone but the chanters are silent. Reverence fills the air. Cocky adolescents become humble novices, or meek apprentices solemn with responsibility. Flirty young women shed their jewelry, change into traditional dress, and hurry to take their place in the sacred prayer ground. Old and young, paunchy and lean, the men strip to the waist and send their prayers with heart and voice and feet to the spirits that nurture them.

Between dances, the elders formed a talk circle in the camp.

Belatedly, we learned of religious proscriptions. Women observers as well as participants must wear skirts. Only natural garments and adornments are allowed in the sacred grounds. Celebrants must be in bare feet. Alcohol and drugs are forbidden. Cameras are confiscated if they are seen, and pictures forbidden. Menstruating women are prohibited. Gratuities are expected from outsiders. After the ceremonies, gifts of tobacco, amber, flowers, fruit, or money are given to the participants.

We are guests at their ceremony; and of course, we agree to comply. As we pants-clad women step beyond the immediate area of the sacred ground, the sun instantly appears. Earth’s harmony has been restored.

The ceremonies last from day-break to day’s end, but Jesús has returned, and we must leave. Jesús has brought a seven year old boy back with him. Each of them, walking, will lead one of us, riding a horse, down the mountain.

The descent is no less hair-raising than the ascent, except that this time we can see the peril. Again the horses slide on the muddy path; again they appear poised to take us over the precipice. But Jesús is smiling, and his young friend is skipping down the path. After we have been delivered to our homes, they will go back up the mountain together, to join the dancers and to retrieve Jesús’s horse. That will be six trips up or down the mountain for Jesús today, and it’s not even 3:00.

I am humbled, awed, sunburned, and exhausted.

Many of these mountain Indian women travel that primitive path with their children every day, acquiring carts laden with looms and weaving to sell at the lake’s side in Ajijic. And at dark, they push their weary bodies back up that mountain, and then fix dinner for their families, only to fall asleep in a tent with a dirt floor, and do it again the next day.

But for this one weekend, every year of the celebration, they can be dancers of the sun, graceful and strong and important.

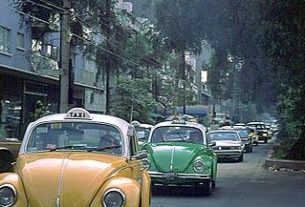

And I wish, oh how I wish, I had pictures to show you. Here is the mountain, at least, for whose safe transport Johanna and I thank Mother Earth.

August 9, 1998. Lake Chapala, Jalisco