In December in Oaxaca there’s a fiesta almost every day, which makes this colonial city one of the most popular holiday destinations for both foreigners and Mexicans. We describe below the main celebrations. For details on other events which are sure to pop up, check with the tourist office at García Vigíl and Independencia across from the post office, or at the City tourism offices next to La Soledad. Many cultural events are held at La Casa de la Cultura. Read the free tourist newspapers which you can find in money exchanges, restaurants and hotels.

Following are some of the highlights that await visitors in December.

DECEMBER 8 – Feast of the Virgin of Juquila ( La Virgen de Juquila)

In the city, activities begin just after midnight and continue through the day on Calle Mártires de Cananea in Infonavit. In and near the Capilla de Juquila (small shrine honoring the Virgin), and in the church at San Juan Chapultepec, you’ll find religious activities, processions, music, carnival rides, palo ensebado (greased pole), food and fireworks. The reason for the fiesta, however, originated more than 400 years ago in Santa Catalina Juquila, a small Chatino village approximately 175 kilometers from Oaxaca or 100 kilometers from the coastal resort of Puerto Escondido.

In this village there is a very special shrine which houses a small statue of the Virgin Mary. According to its history, the statue was brought to Oaxaca in the mid-sixteenth century by Father Jordan, assigned to teach in the city. When he left the city for another assignment, he gave the statue to his servant who returned to his village of Amialtepec near Santa Catalina . As time passed, there were reports of miracles associated with the statue of the Virgin, and people from nearby began to journey to Amialtepec to venerate it.

In 1633, a fire burned all the buildings in the village, including the humble thatch roofed temple where the Virgen de Juquila was displayed. On top of the ashes reposed the statue, completely unharmed by the fire. Not even her robes were singed but the “skin” was darkened permanently by the smoke.

After this miracle, the priests insisted on transferring the statue to a more fitting setting in the larger church in nearby Santa Catalina. But it immediately disappeared, only to reappear in the village of Amialtepec. This happened several times before the statue finally came to rest in the church at Santa Catalina. Word of its miracles spread and pilgrims came from near and far to celebrate the Feast of the Immaculate Conception in Santa Catalina Juquila. At the end of the 18th century it was estimated that as many as 40,000 pilgrims from all over Mexico and Central America visited the Virgin.

The numbers are much greater now. At the end of November, pilgrims begin their trek on foot, on bicycles, in cars and special buses, and are still returning to their homes as late as December 17. This is an interesting manifestation of faith or superstition, as you wish, but it is also a definite traffic hazard. If you are driving on the international highway or on Highway 131 (the road to Sola de Vega), please watch out for them. They travel by day and by night and do not always have adequate lighting.

DECEMBER 11

An interesting custom honoring the Virgin of Guadalupe takes place on the eve of her feast day, in the Llano Park in front of the Church of Guadalupe. Throughout the day, parents take their young children to the church to be blessed by the priests. The boys are dressed as Juan Diego and the girls as simple native girls of that period. Carnival rides and food stands fill the park.

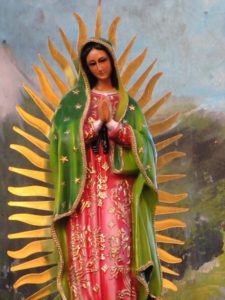

DECEMBER 12 – The Feast of the Virgin of Guadalupe

( La Virgen de Guadalupe)

The Virgin of Guadalupe is revered as the patron saint and Queen of all México and in Oaxaca she is honored with a novena (a nine-day prayer series that ends on this day). Las Mañanitas (a song for birthdays and Saints’ days) is sung before the rosary at dawn, about 5 a.m. There are many activities associated with this day, some religious such as the calendas (religious processions), as well as music, fireworks and the carnival rides.

Her celebrated position dates to December 1531 – a scant 12 years after the arrival of Cortés – when the Catholic Virgin Mary appeared to humble native Juan Diego near what is now the City of México and directed that a church be built on that spot. Juan was not taken seriously by authorities who didn’t believe his vision until, on a subsequent appearance, the Virgin told him to fill his cloak with roses which miraculously sprang up in that rocky place, and to take them to the bishop. When he emptied the roses at the feet of the bishop, there remained as if painted on his cloak the image of the Virgin as she appeared to Juan and as she is still depicted. This was taken as a sign from heaven and the church was built and special devotions instituted to the Virgin of Guadalupe, as she was named.

This devotion grew to be so important that in 1754 a papal bull was issued proclaiming the Virgin of Guadalupe as the Patroness and Protector of New Spain. In 1810 she was adopted as the symbol of Mexican Independence and in 1904 Pope Pius X elevated the church built on the site to the category of basilica. Every year, hundreds of thousands of Mexicans make a pilgrimage to the shrine to honor her, many ascending the stairs on their knees.

DECEMBER 16 – First of nine traditional Posadas, one each night, including Christmas Eve

The tradition of posadas began with the publication of a papal bull in 1586 ordering a ” Misa de Aguinaldo,” literally a Christmas Gift Mass. This was a kind of novena to take place each of the nine nights prior to Christmas Day. It was originally held in the atrium of the church, interspersing tableaus and scenes and finishing with the breaking of a treat-filled piñata. As this tradition became more popular, it gradually evolved to where, today, posadas take place in homes more than within churches.

In various neighborhoods, a different host each night represents the establishments where Mary and Joseph were refused admittance. The roles of Mary and Joseph, angels, wise men and others are assigned to neighbors and family members. In the traditional Posada, the pilgrims arrive at the designated house and request shelter. The request and the refusal are sung as antiphon and response and after several exchanges, the doors are opened and the pilgrims admitted. Inside, they find the host has prepared gifts (aguinaldos) of sweets and fruits for the children. There is music and conviviality, and as a finale the piñata is broken.

This is repeated each night and on the last night a doll, previously blessed by the priest and representing the infant Jesus, is delivered to the crèche in the church. This tradition, practiced by family and neighbors following ritual and custom, is a beautiful and moving celebration. Unfortunately, it is dying out in the cities or has turned into a nine day round of parties. If you have an opportunity to see or participate in an authentic neighborhood posada, don’t miss it.

DECEMBER 18 – Feast of the patron saint of Oaxaca, the Virgin of Solitude (La Virgen de la Soledad)

According to legend, in 1620 a mule train camped outside the city of Oaxaca discovered an extra mule which did not belong to anyone in the group. The mule refused to move and when prodded rolled over and died. When the pack it carried was opened, it was found to contain the statue of the Virgin of Soledad. Taking this as a sign from heaven, the inhabitants built first a shrine, later a church and finally the imposing basilica which stands today on the spot where the statue first appeared. The statue was clothed in luxurious velvet robes embroidered with gold and pearls and wore a golden crown, much as you see her now in the Basilica.

Because of this miraculous selection of Oaxaca by the Virgin, she became the patron of not only the city but the entire state, as well as of the mariners who sailed to and from her ports. The special devotion of the sailors was so important that many walked from Huatulco and other parts on the coast, often barefoot, to worship at her shrine. And they didn’t come empty handed; many brought pearls, gold and other precious stones as tokens of their devotion.

Apparently at some point during the mid-nineteenth century, many religious treasures were hidden rather than turned over to the state as required by law. Some of these were forgotten and lost. But not those of the Soledad.

The Portal de la Clavería, where the Hotel Marqués del Valle is now located, had been part of the treasury of the Archdiocese and the Cathedral prior to the Reform. In 1888 a young man leased part of the Portal to relocate his store. His store, the Pabellón Nacional, sold fine fabrics and other fine imported items popular with ladies of the city.

Soon it became necessary to knock down one of the interior walls to provide better space utilization. Once the dust had cleared, the workers discovered a space hollowed out in the floor beneath where the wall had been. In the hollow they found a large iron chest – a veritable “pirate’s chest” – and a somewhat smaller wooden box. In the smaller box was a totally rotted velvet robe of the Soledad, embroidered with gold and pearls, while the chest was full of pearls and other stones which had been brought over the years by the mariners.

The owner of the store, Luis Bustamante, bought the finest velvet available in France and drew a pattern for the nuns to embroider the new robe, using the undamaged gold and pearls. These treasures were then presented to the Basilica of la Soledad.

The Virgin had a number of other robes, jewels and golden crowns. Then several years ago, almost exactly 100 years after the discovery in the Portal, there was a robbery of some of the Virgin’s jewels. To date nothing has been recovered and the crime has not been solved, although recently several suspects have been detained. We don’t really know exactly what was stolen and what remains but there has been no mention of the chest full of jewels. The patroness of Oaxaca still has a crown and a number of beautiful robes but where is her treasure given over centuries by her devotees?

DECEMBER 23 – Night of the Radishes (La Noche de los Rábanos)

This undoubtedly is one of the most unusual fiestas in the world and the only one of its kind. Contestants from the city and nearby villages carve radishes into detailed figures and elaborate scenes and compete in a contest sponsored by the City of Oaxaca on the night of December 23.

To fully appreciate the pageantry of this event, you must first change your idea of what a radish is. We are not talking here of a round red vegetable approximately one inch in diameter that dresses up a salad. Nor are we referring to a nice white burn-your-tongue horseradish. Imagine a nice red plant that may be as long as two feet and up to about four inches in diameter. That is the radish we are talking about! These radishes are specially grown, left in the ground for months and months to attain their giant size.

Although La Noche de los Rábanos is a City-sponsored event attended by thousands, the beginning of this tradition dates back more than 200 years. Before the Spanish arrived, many of the plants we know today didn’t exist in the New World. The settlers, and especially the friars, who arrived in Oaxaca brought many fruits, flowers, trees and vegetables, including the radish.

During the colonial period Oaxaca was a very small city in a lusciously fertile valley. The biggest plantation serving the city with fruits and vegetables was in Trinidad de las Huertas, roughly the area between La Noria Street and several blocks south of the Periférico. The harvest was plentiful and so much of it was brought to be sold in the market which was then set up alongside the Cathedral and in part of what is now the Zócalo. At that time there was no park, no bandstand or landscaping.

As it happened, one year around the mid-eighteenth century, the crop of radishes was so abundant that a section was not harvested and lay dormant for months. Then in December, two of the friars pulled up some of these forgotten radishes and were amazed and amused to see the size and shapes. Imagine a red carrot gone wild. It not only grows fatter and longer but it divides and grows out into strange shapes. So the friars selected “demons” and “monsters” and brought them as curiosities to the Christmas market held the day before Christmas Eve.

These huge, misshapen roots soon began to attract crowds to the area where the vegetables were sold. It was not long before they were being formed and carved to give a greater variety of shapes and figures. From this beginning evolved the idea of fashioning the radishes into nativity figures and eventually a competition began, to create more original and more perfect figures.

In 1897 the City sponsored the first contest with a prize for the best nativity scene. Thus for more than 100 years the figures have been displayed and judged on December 23. The Night of the Radishes is no longer limited to Nativity scenes. Now you may see Guelaguetzas, posadas, calendas and other representations of Oaxacan life. Also, as there are fewer growers who carve the radishes, the city now cultivates the special radishes and permits entries from sculptors and others who want to try their hand. Also, there are now scenes made from special flowers and corn husks.

The competing tableaus are set up in the Zócalo late in the afternoon of the 23rd and people start lining up to view the artistry as early as 4 p.m. although the judging and awarding of cash prizes isn’t done until around 9 p.m. To accommodate the ever-increasing numbers of spectators, the city builds a two-level ramp that encircles the displays.

Unfortunately, the radishes wilt in just a few days, so it is not something that one can take away or keep. Still, it is a festival unique in the world and should not be missed. You will be amazed at the intricacy and ingenuity of the artists. Be sure and take pictures because your friends will never believe it otherwise when you try to describe the Night of the Radishes in Oaxaca.

DECEMBER 24 – The Good Night, (La Noche Buena)

Tonight we have the last of the posadas, followed by the calendas, the name given by the Catholic Church to the calendar of saints’ days and thus by extension to the procession and festivities with which each was celebrated.

When the Spanish arrived in the “New World” they brought with them the religion, priests and customs of the old. In many cases rites and ceremonies were more or less superimposed on indigenous customs to “convert” them to Christian celebrations, often resulting in a new amalgamated tradition. In the case of the calendas, there seems to be little or no native influence in the initial style. The newly arrived friars used large banners painted with images and scenes to teach their religion. These banners evolved into the standards of each saint and parish church, which still exist today.

From earliest colonial times to the beginning of this century, the calendas flourished in Oaxaca. Although the custom seems to be dying out, during the Feast of La Soledad and Christmas Eve, you will still find calendas, although not so elegant as in years past.

For days before the date of the calendas, the parishioners prepare the allegorical cars (floats) and costumes. On December 24, the Good Night, the processions form in churchyards throughout the city, march through the streets, eventually circling the Zócalo several times before returning to the church, where the infant is placed in a manger and the cock crows for Midnight Mass. Included in the procession are rockets and fireworks, decorated floats, marmotas (translucent paper spheres lighted within and carried aloft on poles), and “giants” introduced in the 18th century. These are comical, bigger-than-life paper mache people whose arms flop around as the person hidden inside struts and dances.

DECEMBER 25 – Christmas Day ( La Navidad)

The city is quiet. Action has moved into churches and to family celebrations at home. You will see very few Oaxacans in the streets, stores and restaurants. The Zócalo will be virtually empty of all but visitors. Here, there is no native Oaxacan tradition; everything has come from Spain, Europe and the United States – Christmas trees, Santa Claus, turkey dinners and exchange of gifts. A typical Oaxacan dish that has come to be associated with Christmas dinner is a salad of leaf lettuce with radishes and a sweet vinaigrette dressing.

OTHER MONTH-LONG FESTIVITIES

During most of the month, the Zócalo and nearby streets are jammed with booths of handicrafts, clothes, and food. The town center is turned into a virtual fair. Wander around the Alameda (the park in front of the main cathedral just north of the Zócalo) and sample some of the special, very sweet Oaxacan desserts, such as cocada, carlitos, turrones and many more. And don’t forget the buñuelos, a special sweet traditionally prepared at Christmas and served at stands alongside the Cathedral.

After eating the buñuelos, it is the custom to break the clay serving plate. One legendary version of this tradition is that during the 19th century, when there were several epidemics of cholera, orders were given to break the plates to avoid contagion. However, today it is considered good luck when your plate breaks into hundreds of pieces. This lighthearted tradition not only alleviates frustrations, keeps your throwing arm in good shape, makes a nice crashing noise but it’s also good business for the potters who make the plates. So, join in the fun and break away.

NEW YEAR’S EVE

Here we are at the end of December, ready to sing Auld Lang Syne with a tear, a smile and high hopes for the best New Year yet. In Oaxaca, you’ll make your toasts with sidra, a carbonated hard apple cider. This Mexican “champagne,” like all champagne, can be dry, sweet or pink, and consumption in the holiday period is measured by the vat. Should you go out for a special year-end dinner you will probably indulge in elaborate pork dishes or bacalao (dried cod, richly prepared), with a wide selection of accompaniments. Don’t fail to eat your traditional twelve grapes – one for each month – for good luck, and to make your resolutions which this year you are definitely going to keep.

JANUARY 6 – Feast of the Three Kings

There is still one more holiday festivity — The Feast of the Three Kings. It is on this date that children traditionally receive gifts, commemorating the gifts carried by the Wise Men to the Christ Child. While Santa Claus has gained in popularity in Oaxaca, it is to Melchior, Gaspar and Baltazar that letters are written and who bring gifts to children who have been good all year.

Also on January 6, family and friends gather to share the rosca, a cake something like a coffee ring in which little plastic dolls are hidden. (You can buy these in bakeries if you don’t have facilities to cook your own.) When the rosca is cut, everyone whose slice contains a doll must cooperate for the final party of the season on February 2. Depending on the number of people and the size of the rosca, there may be as many as six dolls in one cake, thus spreading the cost for the party or possibly originating more than one party.

If you haven’t written to the Kings or if you weren’t good all year, you can still share in the rosca so that you will be included in the party on February 2, either as host or guest.