Juan Mata Ortíz is a small village of potters, farmers and cowboys in Northern Chihuahua. About 30 years ago, an unschooled artistic genius, Juan Quezada, taught himself how to make earthenware jars in a method used hundreds of years ago by the prehistoric inhabitants. Now, his works are known worldwide and over 300 men, women and children in the village of less than 2000 make decorative wares. Much of the polychrome and blackware is feather light and exquisitely painted.

Many of the potters are also cowboys and farmers. These stories serve to document the art and the people in this unassuming pueblo, which is often called “magical” by the relative handful of tourists who visit. Enjoy this other view of Mexico.

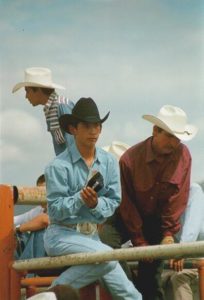

The young man straddled the scarred metal tubing of the chute, adjusted his black sombrero and stared down at the bull beneath him. Although only 13, he looked older and was already an experienced bullrider. The beast jammed into the narrow enclosure below was also black. He bellowed in anger at his confinement. Soon, the two would spend a few intimate seconds together, bounding across the dusty field ringed with cars and pickups. A band would play and people would cheer. With any luck, both participants would emerge unscathed.

A jaripeo is a form of rodeo held in small communities across the vast cowboy country of Northern Mexico. The singular event is usually bull riding with men, boys and occasionally even young women paying a small fee to take part. Jaripeos are usually held around festival days. Mata Ortíz and many other towns and villages will hold these events on November 20th, anniversary of the anniversary of the revolution begining in 1910 against the dictator Porifirio Diaz.

In Mata, the jaripeo is held in the baseball stadium. Spectators fill the stands and line the outfield walls. Those who want an intimate view, drive their vehicles into the stadium and back their fenders against the wall. Most arrive in trucks and soon chairs are set up and beer coolers are opened in the beds of the pickups.

At this event, held in August, 60 bulls and steers (bulls without an important operating part) were herded from the plain across the river during a driving rainstorm the evening before. The morning of the jaripeo was bright, clear and fresh. Each animal was sorted in a corral and numbered with washable spray paint. A committee matched the bulls to the men and boys who wanted to ride. Care was taken to ensure the massive Brahmins and other large animals were not allotted to the youngsters.

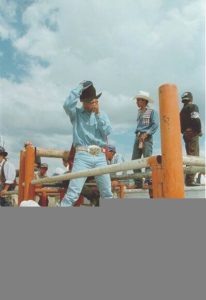

Shortly after 2 pm, the stands were flowing with fans, trucks were jamming themselves against each other in the outfield. Beers and sodas were sold or being hosted from the coolers. Vendors were wheeling their little carts around the inside perimeter, selling paletas and ice cream. A local band blared the Musica Norteña so popular in northern Mexico. After a parade around the field by the three designated queens—dressed in black and gold charra regalia—and their cowboy escorts, everyone waited eagerly for the first rider.

A bull was prodded into a small chute and a helper strapped the two-handled pretal to the first animal. The rider who had been alloted the number of that bull gingerly slid onto its back and grabbed the pretal’s handholds. The gate opened, the bull shot out like a bouncing, weaving cannonball and the band played. The rider survived his trip careening across the field and finally leapt to safety. Three cowboys galloped out from a group milling in the outfield to attempt to lasso and then bulldog the bull to retrieve the pretal. The heroic rider, meanwhile, was picked up by another cowboy for a triumphant canter to the queens to receive a congratulatory kiss. Already, the next rider was preparing for his duel with a steer. And so went the afternoon.

It was midway through the day when the youngest rider, the 13-year old, pulled on his gloves and climbed the chute. The bull beneath him was the bigger than the other two he had ridden the previous year. But, he was bigger and stronger, too. His father checked that the leather strap and wooden handhold on the pretal was secure and nodded to his son.

Using the metal bars as steps, the boy eased down the chute, dropped onto the bull’s black back and dug his knees into the animal’s sides. Gripping the pretal tightly with both hands, he nodded and the gate opened.

The young bull launched himself, bounding past a cluster of cheering onlookers, and took off bouncing and twisting towards the imagined freedom of the outfield. The boy’s hat caught the wind and disappeared behind him. His legs flew up, but he leaned back and maintained his balance. Two outriders flanked him as the bull charged past second base. The youngster hung on and wore his ride out. Near the outfield fence, the bull slowed to a trot and his rider leapt from his back. The animal meekly allowed a cowboy to remove the leather strap while the boy mounted another cowboy’s horse for the triumphant ride across the stadium to the awaiting jaripeo queens.

The jaripeo is an all-day social event and the bullriding is just part of the fun. All afternoon, the young men circle the outside of the baseball stadium on their horses, catching the eyes of many a fair señorita. If a boy is lucky, one of the girls might allow him to take her on a short canter. Afterwards, I asked my young friend why he wore his best clothes while riding the bull, instead of work clothes he wouldn’t mind getting dirty.

“To look more handsome,” he replied.

It must have worked, for he had no trouble finding girls to ride around the stadium with him for the rest of the afternoon.