Juan Mata Ortíz is a small village of potters, farmers and cowboys in Northern Chihuahua. About 30 years ago, an unschooled artistic genius, Juan Quezada, taught himself how to make earthenware jars in a method used hundreds of years ago by the prehistoric inhabitants. Now, his works are known worldwide and over 300 men, women and children in the village of less than 2000 make decorative wares. Much of the polychrome and blackware is feather light and exquisitely painted.

Many of the potters are also cowboys and farmers. These stories serve to document the art and the people in this unassuming pueblo, which is often called “magical” by the relative handful of tourists who visit. Enjoy this other view of Mexico.

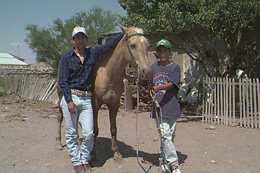

I finally bought a horse in my little village. I figured it was about time: I’m surrounded by cowboys, I used to ride and I do love most four-legged critters, including horses, mules, burros and elephants. When I’ve wanted to ride in Mata Ortíz, I have had to borrow one. Kind of like a rent-a-car (although it’s free), it just didn’t feel completely comfortable.

My friend Jesus agreed to take care of the caballo on his land, if I bought one. I was mulling the deal over for several days when he brought me a palomino. A short palomino. I was enamored. Palominos are beautiful and the distance to the ground wasn’t far, if the horse rode in one direction and I flew in another. Granted his coat was a little scruffy — it was late winter and he looked a little like a hippie. But, I was assured the spring coat would be golden.

How old is he, I wondered? Everyone shrugged. Quien sabe?

I had no experience in buying a horse.Examining the gelding, I felt a little like I was in a used car lot, but there were no tires to kick. I checked out the teeth, but that was sort of like kicking the tires — I had no idea what I was looking for. (They were sloppy, yellowish-white and didn’t appear worn down). “I’ll need to think about it and take him for a test drive,” I told Jesus.

I consulted an American pottery trader, Richard, who came to town. He’s a friend of mine and is a horseman in his own right. When he viewed the palomino, he asked, “How old is he?” More shrugs and quien sabes. “Good chest,” Richard approved. “How much?” I told him and he agreed the price was right.

After two test rides out into valley and down the river, I purchased the palomino and christened him Oro, Gold. We placed him with some other horses in an alfalfa field outside town to fatten him up and I didn’t see him for three weeks as, sadly, I had business in the United States.

Returning to Mata after a trip to El Paso, I found Oro waiting for me at Jesus’ house. At first I didn’t recognize him — he was no longer palomino. The mane was still white, but his coat was now a mixed paint of white, orange and café. He was shedding his winter coat. Hmm, I thought, maybe I should rename him ” Más o Menos Oro,” as in “More or Less Gold.” Although surprised at the change, I was still happy. The coloring was unique.

As the spring wore on, his coloring continued to change, and now he is indeed gold, with a short, definitely un-Trigger-like white mane.

Two young friends and I went riding into the mountains the other day. The boys are a Mutt and Jeff team of 14-year olds. António is tall, looks 16, and is painted into the saddle when he rides.He’s a natural cowboy and loves to ride bulls (see ” Jaripeo–the Drive-in Rodeo“). Beto is short for his age, also loves to ride, but doesn’t have a horse and has little experience as a ” vaquero.” Still, compared to me, he is a pro. As I re-learn my horsemanship I am reminded of a Denver Nuggets basketball – one that bounces wildly and without direction.

The three of us sloshed the dribble of a river, crossed the valley which is being dusted brown with a new drought, and climbed into the foothills of the Sierras. We had no goal in mind, but the boys had lassoes attached to their saddle horns. António was keen to use some calves as targets. Searching the arroyos, which lace the hills, we finally came upon a cow and her calf.

From a distance of about 50 yards they watched suspiciously. What are these humans after now? Whatever it is, it probably wasn’t good.

We marched three abreast down the hillside towards them. Dressed in cowboy hat and shirt, jeans and boots, I actually felt like a vaquero for an instant. At this moment, I thought, that cow doesn’t know I can’t rope a fence post. I sat a little straighter in the saddle. What a feeling of power. Then António brought me down to earth.

He directed Beto to cut to the right and start the chase, while he would ambush the calf further down the gully. The game began. Beto cantered after the cow and her calf and António rode 100 yards down the arroyo to await his prey. The mama cow, however, was wily and she and her calf evaded the boy and charged up the hillside. The next few seconds are etched in my memory forever.

António and his powerful black mare surged up the rocky slope in hot pursuit. When the bovines reached the summit they sped across the ridge. Close behind, silhouetted against the cobalt blue sky the mare tore after them, “Toño” hunkered low, left hand twirling the lasso over his head. Robert Redford would have been impressed with the shot. The kid cut the calf away from its mother and turned it down the hill towards the arroyo where Beto now waited. Reaching the sandy bed, António whipped out the rope and snared the calf around the neck. The mare snapped to a halt and braced her legs, pulling the lasso taut as her rider curled the end around the horn.

” Las patas, las patas,” António urged. “The legs, the legs.” Under his friend’s direction, Beto managed to lasso the hind legs of the bawling calf on his second try. “Now, pull back, pull back.” The smaller boy urged his horse backwards and legs stretched out, the calf fell on his side. António leapt to the sand and quickly freed the animal, which scooted away unharmed to his worried mother.

The exercise was complete.

Down here, you learn by watching and then doing — practice makes perfect. In past years at brandings, António has been content to merely hold the calves down while the hot iron is applied.

This year, he will be manning his own lasso.

We rode down the hill, back towards the village and a soft chair for my old backside. I lingered behind the boys, watching Beto listen attentively to roping advice from his peer and mentor. I had learned a lot that day, too, and promised myself that I will rope my own calf before the end of the summer.

My palomino, Oro, has a reputation of being a great cow pony. Several times during the chase, his ears perked in anticipation. Then, he would look over his shoulder in disgust at the dude on his back. I made the same promise to him. Before the end of the summer, Oro, we’ll be roping calves.

I hope.