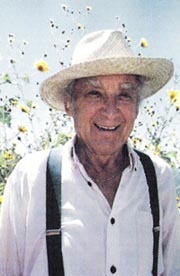

Some years ago, during a lovely spring afternoon at his Mexican home overlooking Lake Chapala, artist Georg Rauch needed something to take to a monthly gathering of artists and writers in Ajijic. While fighting for the Third Reich on the Eastern Front, he had written letters to his mother – in all some eighty-four letters and drawings. He had always carried these letters with him… to New York, then to Mexico, then to California, then back to Mexico… to Jocotepec, where he and his wife Phyllis have lived now for thirty years. That afternoon he opened a few of them and, for the first time, read them.

He showed three of them to his wife Phyllis who was at work in her cactus garden. She was captivated by what she calls tales “of merciless cold and unending snow… of men dying in the snow-filled foxholes.” She translated “the letters scrawled with pencil on tiny scraps of paper and typed them out on the old electric typewriter.” The audience that evening was powerfully impacted.

Later at home, Georg began to re-read all of those letters, which of course he had stopped writing after he had been captured by the Russians. He almost died in a Russian prisoner-of-war camp near Kiev. But luckily for Georg and for the world of art, World War II ended and in October of 1945 the twenty-one-year old was transported back to his native Austria. His formerly sturdy body, which stood at 5’10,” had wasted down to a mere eighty four pounds.

Now, at their hillside home in Jocotepec, Georg wanted to tell a new generation about “how it really was.” Georg, a professional artist for more than thirty years, put his paints and brushes aside. And then, in a little covered shelter near their pool, he began writing, by hand, on yellow pads. All the tiny details of daily life on the Eastern Front began to come back to him and he wrote for weeks and weeks, like a man obsessed. His wife says he stopped “only to eat and sleep.”

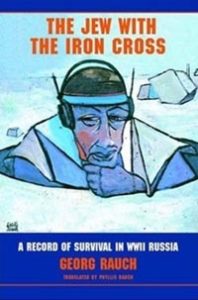

Those efforts became his book, The Jew with the Iron Cross: A Record of Survival in World War II Russia, just published this month.

A Jew in Hitler’s army? And the Iron Cross? Germany’s medal for bravery on the field of battle?

Georg Rauch was born in Salzburg, Austria in 1924. His family moved to Vienna when he was four years old. Although his mother was a Baroness and his father an engineer, following the devastation of World War I, the family had fallen on hard times. As a young boy Georg enjoyed “inventing” things, and his mother – to whom he was much closer than to his father – was intent on introducing the bright boy and his sister to the world of music and art. His mother liked to draw and paint and she gave the young Georg his first set of watercolors. At his home in Jocotepec, Georg told me that “My poor but happy childhood ended abruptly when I was fourteen and Hitler occupied Austria.”

It was in March of 1938 that Hitler visited Austria (Hitler’s native land) to declare the union of German with Austria, to the delight of many Austrians who had longed for such a union following the break-up of the Austria-Hungarian Empire by the Allies after World War I. Wanting to be like the other boys, fourteen-year-old Georg, tried to join the popular Hitler Youth. But, although Georg was not Jewish, the certificates he had to carry with him clearly showed that his mother was one-half Jewish; therefore to the Third Reich, Georg himself was Jewish because he was of Jewish blood. His former companions avoided him and he himself did not understand “what a Jew was.” In fact he had been baptized Catholic.

He became a loner. His teachers ignored him. People of Jewish blood were not allowed to go to a university, or to become teachers or doctors or lawyers. His mother became active in the underground, hiding Jews in the attic of their home, and Georg helped her by buying food stamps on the black market. Jews would trade in whatever they had – including valuable jewelry and pieces of art – for food. Georg, with his inclination toward inventing things, built alarm systems to signal when the solders were arriving. He also made illegal short-wave radios so that they could listen to news of the war on BBC.

But by 1943, when he was eighteen and no longer wanted anything to do with Hitler and his war, Georg was drafted – as a Jew – into Hitler’s army. He was sent to the Eastern Front to fight against the Russians. The Jew with the Iron Cross is largely the story of those war years. His skill at building radios eventually saved his life as he was assigned on the Eastern Front to a communications unit which, although surrounded by combat, enjoyed at least a little protection because of the importance of their activities. In 1944 he was captured by the Russians.

After the War

At the end of the war, in autumn of 1945, Georg returned from the Russian prisoner-of-war camp quite broken in body and almost in spirit. His mother, with her wisdom and special talents, fed him lightly the first few weeks until he began to recover. He ate lots of vegetables that she raised in her garden. Sometimes she traded lettuce and tomatoes with American soldiers for cheese and butter and corned beef and peanut butter. “When my sleep was wracked by nightmares of the war, she would gently wake me up and ask me to tell her about my dreams. It was probably this intuitive wisdom that helped to heal my soul….”

In Vienna he tried to study architecture and life drawing, but his body, particularly his joints, was wracked with pain. Around Christmas in 1947, it was discovered that the tuberculosis, lying dormant since his release from the prisoner-of-war camp in Kiev, had become active and had moved into his bones. Streptomycin was not yet available.

Georg was sent to the Stolzalpe Sanatorium in the Austrian Alps. Eighty percent of his body was covered by a cast. But daily, in addition to a healthy diet, he was wheeled out into the high mountain air and sunshine. It worked.

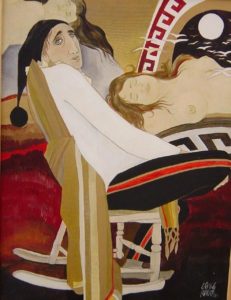

One day his mother brought him a book of work by artist and fellow countryman Egon Schiele. (Georg was also influenced by another countryman, Gustav Klimt.) His old interest in drawing resurfaced. “I have often said that the twenty two months spent in Stolzalpe were my best art school. Each day the patients were wheeled in their beds out to the terrace where they lay in the healing sun. After I had obtained paper and pencil, I spent many hours drawing the nude bodies of my fellow patients – only the males, of course. They provided a variety of perfect, relaxed models – better than any life drawing class could offer.” And he could draw them “up close,” literally within reach. Much of Georg’s later work was of reclining female nudes, often seen close up, and generally resting or sleeping.

Now twenty six years old, Georg was discharged, with a permanent limp because of a fused hip joint. While he was wondering what to do with his life, “My mother said to me, ‘Why don’t you become an artist? You’ve always loved to paint and draw, ever since you were a child.'”

Although Georg thought that was a risky thing to do, because of the confidence his mother demonstrated toward him, he became an artist. “Thus encouraged, I began to paint, using a set of oils we had inherited from a friend, Dora Breuer, who had jumped from a fifth floor window in the Doroteergasse when the Gestapo came to pick her up.”

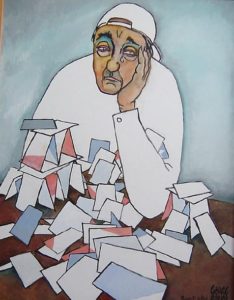

“Lacking brushes, I used my fingers and a palette knife for the first few paintings – a self portrait and surrealistic images of what looked like a city in ruins.” I asked him about that early subject matter and he said: “I came back with a mind etched with indelible things. I could never paint a happy face or a mother and child.” For years he painted the sad faces of lonely men, often as clowns.

As his own confidence developed and his health returned, he began hitchhiking around Europe, painting quaint fishing villages, mountain huts, places off the beaten path in Italy, France, and Spain. He would return with thirty or forty watercolors and the sale of these, along with his small war disability pension from the Austrian government, would keep him alive for six more months.

His first one-man exhibition was in Vienna in 1952, followed by other exhibitions in Vienna, London, Paris, Stuttgart, and Düsseldorf. In the 1960s he began to combine his love of invention and art into moving sculptures. “I dubbed [them] ‘rolloides.’ Each utilized a small motor and a variety of systems for raising balls to the top of welded wire construction from where they tumbled, twisted and slid to the bottom again.”

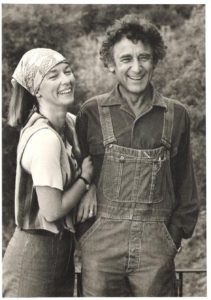

Now enter Phyllis Porter, a young woman from Warren, Ohio. In 1965 Phyllis was traveling around Europe. In a youth hostel in Athens she met a cousin of Georg. After only a few minutes of conversation, he invited her to visit him in Vienna where he was doing a film about his artist cousin, a fascinating man who was building an enormous kinetic sculpture for a playground in Vienna. She postponed, forever as it turns out, a trip to England, and did indeed go the following spring to Vienna. There Georg, who had just divorced, wasted no time in inviting the lovely young woman to go camping with him to the Côte d’Azur and to St. Tropez on the picturesque and romantic French Riviera, a region that had inspired so many other artists… and lovers… in the past. Georg calls this trip their “pre-honeymoon.”

Phyllis returned to the states and in spring of 1966, after nine months of exchanging letters, Georg arrived by boat to New York, which was rapidly replacing Paris as the “art capital of the world.” Georg says, “As a painter, I like sunshine, colors, warmth. I was thinking about Italy, but I did not like the Italians.” Well, he did not like New York much either, partly because abstract, non-representational art was in vogue; but he did become part of the art world there. A Jewish lawyer in New York City bought some of his paintings, and another collector offered him an apartment on 72nd Street. He did a series of successful watercolors in New York City while Phyllis was working as a librarian. They were married on September 11, 1966.

Life In America

Thanks to my fascination with rolling balls, I was invited to build a kinetic sculpture for the 1968 Expo in Montreal.” He did so during the winter of 1966-1967. The following spring another couple convinced them to visit Mexico with them. Although they had only $400 to their name, Georg convinced Phyllis that it would work out all right and that, after all of their expenses, they would return with more than $400.

July found them in very southern Mexico in Tehuantepec, which was “hot, humid, and cheap.” On the way back, they stopped in Guadalajara. There they met the Austrian Consul who bought some of the paintings Georg had done while traveling through Mexico. The consul provided lodging for them in a little inn in El Chante, a few miles west of Ajijic on Lake Chapala. He also introduced them to important people in Guadalajara. Because of the consul, they were invited to a high-class party.

They were told that it was to start at 7:00 pm. They arrived at 7:00 pm. The other guests only began to arrive two hours later. Georg and Phyllis were beginning to understand Mexican ways but, equally important, that same evening Georg sold three more paintings. Already he was beginning to develop a Mexican clientele that would serve him well over the years. On the way home, he sold the last of his Mexican paintings in Salt Lake City. As he had promised Phyllis, they returned home with $900, $500 more than they had started out with.

Almost immediately, the Consul invited them back to Guadalajara to build a kinetic sculpture in front of a shopping mall in Guadalajara. And so the winter of 1967-1968 they rented a house two blocks from the Country Club in Guadalajara and attended lavish parties where they also sold paintings. Phyllis even served as a guide at the 1968 Olympic Games held in Guadalajara. Their winter stretched into two and a half productive years, in which they made so much money through the sale of Georg’s paintings that they were able to travel to Europe for the first time since he had arrived in the states.

In 1970, they decided to move to Laguna Beach in southern California. There Georg began doing silk-screens (inventing some new techniques of course) and Phyllis became a librarian in San Clemente. Georg had always been in love with the human form, particularly the female form, and in southern California he was entranced by “the beautiful bodies, almost naked, basking in the sun on the beach.” Many of his paintings are of nude women, often asleep, often partially wrapped in sarapes and sometimes in gold. During this time, Georg flew regularly to another beach – Puerto Vallarta in southern Mexico – where annually he did one-man shows for many years. His clients in Puerto Vallarta included Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor.

By now Georg was beginning to realize clearly that “America was not my country.” He was disappointed with the direction of art in America and tired of the endless obsession with “money, money, money,” that, like cancer, invaded and then destroyed every aspect of what he perceived to be “culture.” Georg always insisted on going his own way, never choosing the popular path, which at that time was abstract decorations for the walls of the wealthy. His source of art was memory and experience, much of it horrible but much of it also beautiful, and his inspiration rose up out of these memories and experiences and became his remarkable art.

In 1974 on one of his trips to Puerto Vallarta, he took a rather indirect route home to return by way of Jocotepec, a village just west of the little town of El Chante, which had enchanted them several years earlier. There he met a young German and stayed with him in his little house on a lovely hillside overlooking Lake Chapala. The German wanted to sell the acre or so of property just above him. It had nothing on it but “goats and weeds,” but it had a gorgeous view, and to Georg, it felt, at long last, like this was “home.” By then “I knew for sure I would never be a famous artist as long as the non-figurative was in vogue.” But he did know for sure that he was well accepted in Mexico and that the tropical mountains (and perfect climate) of central Mexico were the place for him. And in fact, he supported himself as an artist.

Phyllis, however, was not as sure. She had developed a career as a professional librarian, she was highly regarded in her profession. And although she was fluent in German and Spanish, she was content to be a part of the Laguna Beach community. When Georg returned to tell her that he had bought a lot in Jocotepec just one hour south of Guadalajara and that that would be where they would build their new home, Phyllis was shocked.

But in 1976, Phyllis followed her life companion to his dream in Mexico, and there she built a new life for herself, doing charity work and also painting and writing. That was thirty years ago. That initial shock has turned to love of their home, of their community, and of the Mexican people. Then, twelve years ago, they took a color trip in autumn to New England and on that trip they stayed in little bed-and-breakfast inns. Returning, Phyllis became excited about the idea of building bungalows on their property and running their own B&B, and thus was born Los Dos. They built four exquisite bungalows, with complete kitchens, art work by Georg and a lovely pool heated by a solar mechanism designed, of course, by Georg.

Because of macular degeneration, Georg can no longer paint. But he can still entertain the guests with tales of the artist’s life and illumine them with tales of the desperate life of a Jewish soldier in Hitler’s army, as told in his book.

After thirty years as an artist in Mexico (and close to 2000 paintings spanning more than fifty years as an artist), Georg has been adopted as a “Mexican” artist. Although a few years ago Austrian and German television jointly presented a documentary, “The Life of Georg Rauch,” he prefers now to think of himself as a Mexican artist. Here in central Mexico he found peace. It is fitting that it was not in Vienna but in Guadalajara, at the Museo Ex-Convento del Carmen, where he was honored with a major retrospective show of 50 years of painting. Georg Rauch has lived a remarkable life and created remarkable art. “Nature, unspoiled and pure, with a clear view all the way to the horizon, that magic line symbolizing the distant, the unreachable, the pale blue of the future is both what I see from my Mexican terrace and what I envision when I close my eyes.”

The Jew with the Iron Cross: A Record of Survival in World War II Russia is available through www.Amazon.com, www.barnesandnoble.com, www.paradoxicalpress.com, www.iUniverse.com, www.buy.com and at various bookstores throughout the United States and Mexico. 249 pages. $20.95. ISBN 0595379877