The Aztecs called it tianquiztli, Nahuatl for the marketplace”. Modern Mexicans refer to it as the tianguis, mercado sobre ruedas (“market on wheels” – a term used mostly in Mexico City), baratillo, and many other local connotations. Homeowners use another kind of language to describe the vendors who have set up shop in the street, blocking public access by car. Whatever you may want to call them, it is not hard to notice those open-air markets that spring up magically in your neighborhood one day of the week.

© Susanne Zimmerman, 1997

The original Aztec markets, like the markets of Tlatelolco and Teotihuacan, were famous in pre-Columbian times for their size and variety of produce, but the were stationary bazaars, confined always within the same site. Since that time, the traveling tianguis has evolved with its own unique culture to keep the marketplace conveniently close to the inhabitants of Mexico’s large cities, and smaller towns, also, where due to the low demand of goods, stationary businesses are not economically feasible.

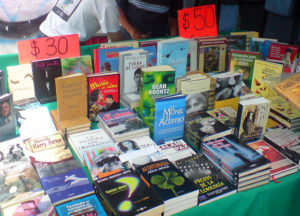

The pink, yellow and other gaily colored fabric roofs of the tianguis begin to appear at their peripatetic destination around 8:00 am. Bundles of metal joists, crossbeams and wooden planks are magically converted into a maze of temporary stands, seemingly without the help of their owners, who apparently spend the early morning hours breakfasting on steaming tamales and sopes served up by vendors already on the scene before dawn. By nine, the street is transformed into a bazaar of stalls that beckon with everything from fresh produce to the latest fashions for Barbie and Ken, from intricately dissected chicken parts to the latest video games. Heavy-duty pine closets, tinseled ceramic lamps, fluorescent plastic buckets and tubs, potted palms, pantyhose and eyelash curlers are also set out for your perusal. The sound systems are cranked up and your local instant Walmart is open for business.

The sights and smells of the tianguis are enticing to natives and foreigners alike; pungent displays of herbs and ground chilies, buckets packed with chrysanthemums and roses, bubbling kettles of pozole (meat and hominy stew), vats of pork rinds sizzling in deep fat, towers of bamboo cages alive with the songs of exotic birds. The cacophony of sounds under those tent-like roofs can be deafening, too. Five different Mexican pop singers scream this week’s hits from five different speakers (almost all pirate copies, their quality directly proportioned to their origin). Vendors hawk their wares, “¿Qué va a llevar?” (What will you take?), and babies cry and fuss from their miniature hammocks slung under tables, or from an improvised crib made from a cardboard box, all a symphonic background to the routine Mexican dialogue of commerce – haggling.

If you are already a seasoned tianguis customer, you will enter one end of the market with one or two empty string bans folded under your arm, and come out the other end stooping under the burden of a week’s supply of onions, carrots potatoes, chilies, watermelon and papaya, broccoli and bean sprouts, rice, beans (both black and pinto) birdseed, chicken livers for your cat, cotton pyjamas for your daughter, a squirt gun for your son and maybe a bag of nasty-looking tree bark that a fat lady with hair growing out of the mole on her chin swears will help you lose weight. If the load seems too heavy for you to carry, there always are able and willing young boys and girls to help you with the burden.

For those of you new to the tianguis, take lots of loose change (no one ever seems to be able to make change for a fifty, much less a hundred peso bill) and look for bargains on produce and fresh flowers; prices are often way below those of the chain supermarkets. Buying meat is not recommended, since traveling butchers are not usually careful about refrigeration. Chicken is sometimes better cared for; you can find parts of the chicken for sale you probably never knew existed in a bird, or any other animal. The rabadilla, or tailbone, for example, is known to make a delicious soup. If you have a good eye for fish and seafood, proceed at your own risk!

The real charm of the tianguis, however, is in the sheer variety of products all gathered together under one (so to speak) roof. If you are the mother of a Barbie doll lover, you’ll find entire stalls dedicated to outfitting the fashion queen in the latest styles. The clothes are all homemade with fine fabrics and accessories at amazingly low prices and are far superior to the chintzy plastic products for sale in the U.S. You can make your toddlers happy, too, by pressing a few coins in their hands and passing by the toy stands where locally manufactured imitations of Ninja Turtles and Jurassic Park action figures are on sale for a fraction of the cost of the real McCoy. OK, so you wouldn’t fool Steven Spielberg, but few three-year-olds will complain. Watch out for the imported models, though. These may cost you three times what you would pay at home (and don’t include a warranty!)

Other bargains to look out for are fun beauty accessories like hair bands and elasticized bows, eye shadow kits, fantasy nail polishes and unusual (for U.S. tones) lipstick colors. If you are “into” birds, check out the vendors who carry their feathered wares stacked in small wooden cages. You may feel uncomfortable seeing parrots and other jungle birds, thoughtlessly crammed into tiny confines so removed from their natural habitat. It is hard to let your conscience be your guide, however, when you consider that if you purchase an animal to save it from this cavalier treatment, you will just be encouraging the vendor to acquire more.

If you are a person with an interest in free enterprise, you may have asked yourself how the tianguis works. Who are those people who set themselves up for business in a different place every day, and where do they come from?

The men and women (whole families, really) who make up these open-air markets on any day are part of a loosely organized, informal commercial association. Each market has its own leader who is responsible for assigning each vendor his position on the street and who secures the necessary permission from the local government for setting up the market in the public thoroughfare. Often, this “permission” consists only of an understanding between parties, and rarely involves any formal paperwork. These informal chiefs are also in charge or regulating trash control. Local government usually sends a garbage truck to collect refuse at the end of the day when vendors have packed and moved on.

The owners of each stand pay their leader a daily quota for the privilege of doing business with the group. The amount varies according to the location of the stall within the tianguis itself, and the kind of neighborhood where it is situated.

The quality of products also varies according to region. Housewives in prosperous areas can select from blushing Georgia peaches, fresh broccoli and plump kiwi, while señoras in less prosperous areas are limited to seasonal domestic fruit, tangerines and melons, and traditional produce like nopales (cactus), green tomatillos and chili peppers. Of course, the quality of the produce will vary; places with apparent low purchasing power are offered dirt cheap, but sometimes somewhat tired goods.

Vendors that cater to the upper crust may offer delicate lace lingerie, fine perfumes and Reebok sneakers, while inner-city merchants deal in more utilitarian wares; enameled cookware, sturdy black school shoes and an infinite selection of knitware for infants.

Where these products come from and how they get to your local street market is a tribute to personal initiative. Vendors of produce and food items are up far before dawn, scouring the wholesale warehouse districts, looking for bargains. Getting products to the marketplace is not always easy, either. Luckier families load up the family car or pickup, but humbler merchants are forced to cart their wares home by taxi, bus or a hired truck; a few hardy souls cart their goods to and from the market in bicycle-driven carts, transporting the children on board for good measure.

The newcomer to Mexico can hardly ignore this unique blend of pre-Colombian tradition and modern day practicality. A short trip to the tianguis is a cram course in the history and culture of Mexico. There are Sears and Walmarts galore in the world, but only in Mexico can you enjoy a shopping experience that mirrors the drama and color of life itself.