As I walked through the gardens of La Nueva Posada, my eyes were riveted on the young indigenous girl seated on the garden wall. Her vivid yellow skirt and blue top reminded me of our magazine’s masthead.

To the Huichols, an eclipse is the symbol of a new era. For the Huichol, indigenous people of Jalisco, the eclipse of July 11, 1991, which plunged Mexico into darkness, heralded the beginning of the Sixth Sun. The Huichols know that each new sun brings marked change to their world. The arrival of Cortez at the beginning of the Fifth Sun changed their world more than any other past incident.

As I drew nearer to the girl, I spotted her two teenaged companions; one wore the traditional heavily embroidered white pants and shirt. The other sported jeans, a t-shirt and boots and topped his “all-American” look with a traditional Huichol hat.

The girl was just starting to encrust a carved wooden crocodile with beads. She had threaded tiny glass beads onto a length of wire as fine as a sewing thread and was pressing each bead into a mixture of beeswax and pine resin evenly spread over a carved wooden form.

I had picked up one of the finished pieces and was examining the intricate colorful designs when I heard someone behind me say in perfect English, “Are you interested in Huichol art?” I turned to face a man with an amazingly laughing eyes and a warm, open face.

“Hi, I am Pedro Guerra Garcia. Can I help you?”

Pedro was taller and larger than most of the Huichol men I have seen. Out of curiosity, I asked, “Are these kids part of your family?”

A grin spread across his face. “Sometimes by the end of the week, when I figure out how much juice and milk they have consumed, and the questions I have answered, I feel like their parent, but no. My father was half Spanish and half Mexican. My mother is indigenous. I didn’t choose to help these people; I am driven to help them keep their ways. It is what is right.”

“Pedro, I need your help to write an article about the Huichols and their symbolic art for my magazine.”

Pedro smiled, nodding his head as he sized me up. Evidently, he decided I was okay, and he started to talk. We struck a bargain. I agreed to explain to you, our readers, about the great needs of the Huichols, the warm peaceful people who are said to be the last descendants of the Aztecs, and Pedro would explain to me the artwork they produce.

Pedro introduced me to sixteen-year-old Libertad, the girl with the yellow skirt, and to seventeen-year-old Alejandro and Alonzo, who is just twelve, but has been working with beads for three years. These three had just come by bus from their remote mountain homes and were concentrating on applying hundreds of tiny glass beads to wooden animals.

“The kids come to me two or three at a time to demonstrate their work here for the tourists.” Pedro said. “They know we can sell their work easier if they are here to meet the people. But they don’t stay long; they miss their homes and mountains.”

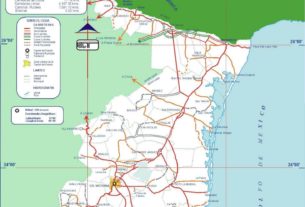

These young people live with their families in nearly inaccessible rugged areas of the Sierra Madre Occidental Mountains of Jalisco. Their tribe has dwindled to about 10,000 people scattered across the borders into the states of Zacatecas, Durango and Nayarit. Their mountain homes have been secluded for centuries, and it is believed that they are the only remaining pure descent of the Aztec.

“Even their native language is from the old days,” said Pedro. “They speak nearly pure Náhuatl.”

While many native people of the Americas have been swallowed up and absorbed, or cordoned off into reservations, being isolated has allowed Mexico’s Huichols to maintain their gentle and spiritual way of life for many centuries.

Pedro adjusted his hat, and then gently stroked a small wooden deer intricately covered with beads. “About 25 years ago, the government began trying to integrate the Huichols into the mainstream of life. They started with building a few roads, a school here and there, and then they put lumber mills in the Sierras. The price of this “progress” has been heavy for our people.

“The roads increase contact with the outside world and that has created an increase in disease. Now they also need money to pay taxes on their land. They have to ride buses on some of their religious journeys, because the old routes have been cut off with fences and other man-made barriers. Because the forests are being harvested, and hunters can get to their lands, the deer they have always offered to please the gods are now nearly extinct.

“That is why we are here,” Pedro’s low voice brought me back from the rugged mountains to the garden where we stood. “We need to earn money if the people are to continue to live in the mountains. They are doing well raising cattle, but it is almost impossible for them to earn enough money farming, and there are no jobs up there; yet their costs are greater every year.”

“Are the young people leaving their homes to work?” I remembered when the family farms up north in America could no longer provide a good living. The young men went off to the cities, and never returned.

Pedro looked out at the lake and replied, “Some have gone to Guadalajara to find work, but these gentle people don’t do well in the cities. They just don’t have the survival skills to go up against that kind of life. Others have gone to the coastal areas to look for seasonal jobs in the tobacco fields. But they are strangers there too, and the chemicals used in the fields are dangerous.

“So, we keep as many people as we can working with their hands in the old ways. They do the beadwork, carve the wood, embroider bags and clothing and create the yarn paintings. By having the kids here, so people can meet them, we can sell more.”

Huichol Symbols in Yarn Painting, Embroidery and Beaded Pieces

I could see Pedro was anxious to change the subject. “Tell me about these designs.” I had read that most of the ideas come from visions and dreams.

“Well,” Pedro picked up a beaded wall piece, “Probably some have come from dreams or from peyote visions.

Pedro’s eyes narrowed. “Do you know about the Huichols’ quest for peyote?”

I had just read about the annual 300-mile trek made by the people into the desert to harvest the sacramental peyote buttons that are the center of their sacred ritualism. For over 2,000 years, all the members of Huichol villages have consumed the plant in ceremonies, even children. They call it the plant of life and believe it to share the spirit of the sacred deer and corn. Through peyote, they achieve a visionary state and obtain a mystical union with the gods.

“For all of these years, the Huichols have been recording their visions in symbols on beaded pieces like these as their offerings to the gods,” said Pedro. “As they walked their sacred paths to the sacred caverns and the other holy places, they dropped colorful little works of art along the trail to please the gods. Because they have no written language, the pieces also told ancient legends, beliefs and ritual ceremonies to help the people remember their history.

“Look at this piece,” Pedro said. “This is what bothers me about modern society encroaching on the Huichols. Look! Here, we have the shamans, the energy of the gods, and the sacred blue deer. But see this part, I had never seen this design before and when I asked Alejandro what it was, he told me it was a truck-a Coke truck.”

Pedro shook his head. “It makes me sad to see the change happening like this. Most of these designs have been passed from father to son for generations. I have seen other kids create designs to express what they were feeling and seeing. Those new designs were all traditional, and the symbols they created spoke of God and the shamans. They included the sun, moon and stars, and the corn and the deer, and the energy that each of these elements released. And now, we see a Coke truck.”

“The word Huichol means shaman or healer. The people know they are the ‘mirrors of the Gods’. That is an appropriate title for a group with no history of war and who celebrate life as the caretakers of the gods helping maintain balance in all other living things. They celebrate being made of the same elements as the world. They know they are made of air, water, fire and earth. In fact, the shamans say, ‘The earth is our flesh. The rocks are our bones. The rivers are the blood of our veins.'”

As Pedro walked around the table he said, “These are gourds that have been cut in half and beaded to be jicaras (prayer bowls). The designs are the petitions, and it is believed that just as people drink water from gourds, the gods will drink up the prayers offered in the bowls, and will understand them better because of the symbols.”

I studied the prayer bowls, searching for the one that resonated with my spirit, as Pedro suggested, with the symbols that best matched my prayers. Then I noticed the boys, work abandoned, playing catch with an orange. Suddenly I realized I had forgotten time, and that there were three very hungry young people waiting for me to leave so they could have their lunch.

“Pedro, I will come back next week to pick out my special prayer bowl. It is past lunch time.”

“Be sure to let the people know we are waiting to meet them.” Pedro’s eyes were still laughing. “Right kids?”

Links to Huichol Legends, Illustrated by Huichol yarn paintings:

If you are interested in learning more about the Huichol people and their art, please visit

Visit the Museo de Artesania Huichol at Eva Briseño #52, beside the Baslica de Zapopan, to view the permanent Huichol exhibits as well as handcrafts for sale. Open daily from 9:30am to 1:30pm and from 3pm to 6pm.

(For more information about the Huichols, or to order Huichol beaded pieces, traditional bags, hats, clothing made to order, contact Pedro Geurrero Garcia at Alvaro Obregon #10 in Ajijic. You can reach him by cell phone (from within Mexico) at 01 (333) 454 4873. Pedro would also like the opportunity to bring some of the Huichol kids to the U.S. and Canada to speak in schools, explain the Huichol culture, or exhibit the Huichol art.).

This article is reprinted with permission of Mexico Insights, publisher of Living at Lake Chapala, a monthly Internet magazine covering all aspects of living in the Lake Chapala/Ajijic area.