The Days of the Dead, celebrated throughout Mexico, coincide with the Christian All Souls and All Saints days, November 1 and 2nd. People who have died in the past year are remembered, their pictures placed on family altars and special food and drink are offered for the souls of the departed.

Last year (1995) I was honored and delighted to be invited to help prepare tamales for these holidays in a small Michoacan pueblo. I don’t even speak Purepecha, the language of the older people of Angahuan, but among the Indians, the heart speaks clearly. The Spanish called these people Tarascan, from the word for brother-in-law, but they call themselves Purepecha.

Last year (1995) I was honored and delighted to be invited to help prepare tamales for these holidays in a small Michoacan pueblo. I don’t even speak Purepecha, the language of the older people of Angahuan, but among the Indians, the heart speaks clearly. The Spanish called these people Tarascan, from the word for brother-in-law, but they call themselves Purepecha.

I heard voices singing in Purepecha to tinkling music on that chilly morning. Wooden houses with steeply peaked roofs were barely visible in the thick mist lying on the pine-covered hills of Angahuan. It was the Dia de los Angelitos, and Lupita invited us to admire the garments she had made for her three-yea-old daughter who had died of pneumonia. It is believed that the little angels, having lived too short a time to fall into sin, go straight to heaven.

On a rough pine table the child’s clothing was laid out: a tiny embroidered blouse and fine huipil decorated with cross stitching which had taken Lupita a month to weave and embroider, a dark skirt, and an indigo rebozo with the ends crossed in front.

Lupita’s child would have been dressed almost like the grownups of Angahuan, except for the addition of a tiny pair of plastic shoes. I doubt they were hers when she lived.; most Purepecha women and girls are barefoot. The mother graciously accepted my offering of earrings to complete the ensemble.

Outside of Lupita’s house an enormous copper kettle of maize was boiling, softening the corn to be made into masa, dough for tamales. Tamales are prepared for the dead, and for those who come to celebrate their lives.

The household altar was festooned with marigolds and brilliant magenta cockscomb, tinsel and fruit. Pan de los muertos in the shape of men and women hung from ribbons. In Angahuan we also saw this bread for sale in the shape of dogs. The belief is that these faithful creatures ferry the souls of the departed across a river to heaven. Although the myth originated with the Mayans, ideas spread from one region to another in pre-Hispanic times through itinerant traders.

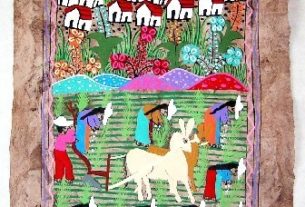

I entered the house and greeted the women in Spanish, ni modo if they didn’t understand. They were dressed in vivid colors: turquoise blouses and yellow skirts, purple and rose, green and blue, their shiny blue-black hair done up in a single braid. I felt like a pale stranger in comparison. They soon made me feel welcome, through a mixture of sign language and translation into Spanish. My husband went with the men to construct plywood frames for flowers.

The dark kitchen was a step below the main room, smoky from the fire in the center. We mixed wood ashes into the dough to preserve the meat. We did an assembly line production, amidst gossip and some dirty jokes. I didn’t understand the jokes, but the quality of the laughter was unmistakable. Some of us spread masa on corn shucks, some shredded the meat, some added salsa and others folded the tamales into neat packets. After several clumsy attempts, amid much giggling, I got the idea.

We completed the tamale-making in the damp chill of the kitchen with a dirt floor, warming ourselves at the fire and passing around a bottle of cana, alcohol made from sugar cane. After a siesta, we accompanied the families to the cemetery where fruit and tamales were offered to children and guests after prayers. The youngsters were full of high spirits and horseplay.

The next night, Dia de los Difuntos or Todos Santos, a parade of people in their finery streamed out of the pueblo at dusk, carrying tall candles and plywood structures decorated with flowers, fruit and bread of the dead. In some areas of Michoacan the path from houses to cemetery are strewn with marigold petals.

Voices sang the strangely repetitive, almost hypnotic music of many centuries past. Bread, tamales and a fermented beverage made from the maguey plant were offered for the repose of the dead. The vigil lasted all night in the light rainfall.

I thought of the magnificent church built upon the foundation of an older temple; it seemed a fitting metaphor for this seamless web of old and new rituals.

(This article first appeared in The Guadalajara Reporter, and is reprinted with Permission.)