Gallery

Forget the crystal clear blue skies that stretch beyond infinity, or the magnificent Sierra Madre del Sur mountain range that embraces the Oaxaca Valley like a mother’s arms. Never mind the proud saguaro cactus, erect like obedient soldiers guarding a cantankerous landscape dotted with lush agave, grazing sheep, a lone herder riding the hindquarters of a burro, staff in hand, hat brim tipped to nose to shield an intense sun. North Carolina was behind me. Ahead was a space defined by ancient history and archeology, and peopled by weavers who had been creating textiles for more than 2,000 years. For me, the landscape was icing on a cake of complex ingredients: wool, natural dyes, traditions and oral histories, Zapotec culture, survivors of Spanish conquest, immigrants to El Norte.

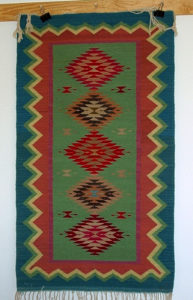

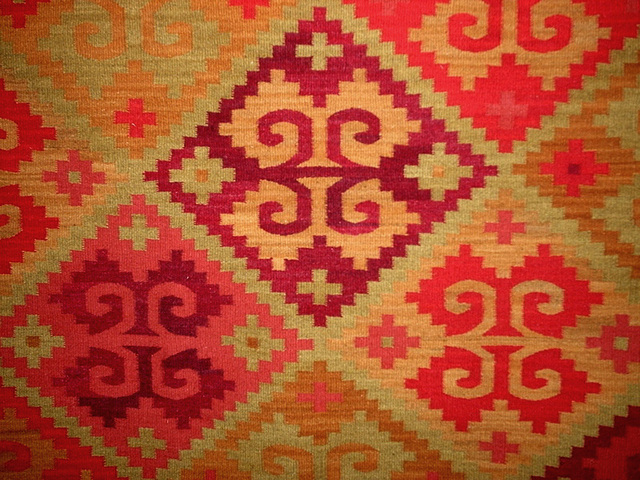

As a textile artist and collector, I remembered my excitement and fascination when first arriving in Teotitlan del Valle almost three years ago. The Zapotec weaving village, famed for its highly decorative, hand-woven wool rugs, is about fifteen miles southeast of Oaxaca city off the Pan American Highway 190. I embraced this visit like an explorer might, in search of the perfect textile to add to my collection. I was on a quest to learn the subtle nuances that differentiate a great Zapotec woven rug, and the weavers who create them. I also wanted to discover great weavers who had not been identified by the popular guidebooks and syndicated newspaper travel writers. I never dreamed that in a few years I would become part of the village, be embraced by a distinguished Zapotec family, and begin to build a casita that would become our home there.

As a white, economically advantaged (relatively speaking), educated Anglo-American, it was important for me to question why I wanted to live in Teotitlan del Valle, an indigenous community of about 8,000 people who have been weaving in wool since the Spanish conquest of 1521. Would I be accepted? Could I make a difference without imposing my own “get it done” style, values and cultural norms? This would be a test of my own cultural sensitivity and ability to navigate across the spectrum of race, religion, class, economics, power, and gender – and likely a whole lot of other stuff.

As a sidebar, I completely understand why Americans and Canadians will buy land and build a home in Mexican gated communities or enclaves that are familiar – it’s just a whole lot easier. North Americans go to Mexico because of the climate and the lower living costs. The retirement dollar expands like an elastic waistband, providing a higher quality of life. Access to good healthcare is plentiful and pharmaceuticals are a fraction of what they cost in the U.S. Living in Mexico is a good deal for many reasons. And living separately there is not much different from living in a gated community anywhere in the U.S.

The most important aspect for me in choosing to live in the village is the sheer joy of the experience. I am immersed! Feet first, jump right in! And, then I say to myself: go slow, be authentic and warm, ask questions and listen, step back and understand that they’ve been doing it this way for centuries for a reason, there are no right answers or the best way. Stay open to the possibilities for yourself and others.

During that first visit, I meandered the alleyways and knocked on front doors, was invited into walled courtyards, made appointments to meet cousins, uncles, and friends of friends. I learned the difference between a natural and chemically dyed rug, the complexity of rug weaving patterns and designs, the tightness of weave and warp thread counts. I was in weaver’s wonderland.

On the fourth afternoon of our ten-day visit, my husband Stephen and I emerged from the pharmacy Internet café (now there is wireless everywhere in the village), made a right turn, and found ourselves smack in the middle of the rug artisans market. A teen-age girl was curled in the corner of one of the corner stalls reading, and an over-eager young man called out to us in clear English, “Do you want to see my rugs?” I was taken aback at his command of the language and was prepared for a perceived slick sales talk! (Talk about cultural disconnect…) We were smiling and walking away when I looked up, saw the rugs, and instantly knew they were exceptional, tightly woven, intricate, made with natural dyes.

This first meeting with then 21-year old son Eric and 19-year old daughter Janet, began our friendship with the Federico Chavez Sosa family. It is a relationship developed over time based on trust, mutual respect, support and caring. I often wonder what life would be like if I had kept walking!

After I returned home, I considered how I might help alter the economic circumstances of this family with whom I had felt an immediate connection. Eric lamented the decline in tourism, the funneling of tourists to only a handful of weavers by tour guides who were commission compensated, the loss of natural dyeing techniques, the out-migration of artists who needed to earn a living. I wanted to do something. Talented families like the Chavez family were struggling.

Over the past two years, we have helped them connect with U.S. universities, museums, and galleries to exhibit and sell their work, demonstrate and lecture about Zapotec art, culture, and traditions because we are committed to cultural preservation. Eric got a ten-year visa. He, his father and sister have toured the U.S. multiple times. They have embraced us and asked us to live beside them on their land in Teotitlan del Valle.

Zapotec society is organized around the guelaguetza system of mutual support. A family member or close friend needs and asks for help, and it is an obligation and an honor to provide it. Reciprocity is always returned with a little extra in the form of money, labor, service or food. This is how posadas, baptisms, weddings and funerals are generally financed. Everyone pitches in — give and it will come back to you. The balance sheet is never equalized.

After we made several visits to Teotitlan and after the Chavez family had been to the U.S. for a series of successful exhibitions, Federico asked us if we wanted to live in the village. We answered with a resounding, “Yes.”

In January 2008, we got a cost estimate from architect Omar Santiago, a family cousin, and agreed on a handshake to begin the casita construction. This was about a year after we had started talking about the project and exchanging multiple rounds of floor plan drawings. We still don’t know how much this 800-square-foot casita will cost, although we have a general idea – about $40 USD per square foot. It’s a pay as you go endeavor. We give Omar a check; he hires the workers, orders the materials and supervises. The big boulder foundation rocks are rolled into place, the cement mixed, the rebar wall uprights secured — a total made by hand endeavor. Today, the foundation is almost complete. It is mid-March 2008, and this first phase has taken eight weeks. We’ve spent about 1/3 of our budget. We communicate via email, with the help of an online translator and with Eric doing intermediary translation, and with our own piecing together of words based on our own limited Spanish vocabulary. I’m thinking the casita will be completed by August. Stephen, who is construction savvy, says don’t plan on anything before December. Festivals, holy days, doctor visits, and other family priorities take precedence.

The next phase will be the construction of the walls. We’re using brick because it doesn’t erode like adobe, although adobe has better insulating properties. Federico likes brick, so that’s what we decided for our house, too. What’s good for him is good for us. I found out from Bank of America that one could make transfers of up to $3,000 USD per month to any Mexican bank without having to pay wire transfer fees. I just read a NY Times article about a World Bank exec who researched and influenced the economics of remittances, reducing transfer fees to developing countries.

A total of $25 billion in remittances are sent to Mexico each year. Families taking care of families. I can imagine how many families we are helping by building this casita.

Our world in Teotitlan operates on the trust of a handshake and commitment to personal agreement. We operate on the premise that it will all work out by the strength of our relationships. I’m sure that the lawyers among us are grinding teeth. So is my family… wondering if I’ve lost my mind? This is not the American way! We are building on a piece of land we don’t own (Zapotec land is owned communally and bequeathed as family holdings not to be passed along to anyone outside the tribe) and putting our personal funds into the construction cost. I trust that life there is good and will continue to be good. I’ll keep you posted.