You can’t isolate yourself. Modernity arrives and replaces what you have.

Changing Dreams by Vicki Ragan and Shepard Barbash is a thoughtfully written and provocative book – one which should be of interest to anyone interested in the culture and the sociological changes taking place in Mexico today.

Changing Dreams by Vicki Ragan and Shepard Barbash is a thoughtfully written and provocative book – one which should be of interest to anyone interested in the culture and the sociological changes taking place in Mexico today.

The text, written by Barbash, is enhanced by Ragan’s compelling photographs, many of them evocative shots that hold their own as individual studies. In short, the book is a sensitive overview of a region in transition that has been movingly presented by this talented husband and wife team.

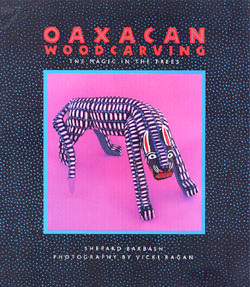

In 1989, Ragan and Barbash left Mexico City for Oaxaca, which was then as it is now, one of the poorest states in Mexico. During their stay, they became entranced with the work of the local woodcarvers who were eking out a living with their colorful alebrijes (brilliantly painted wooden figures full of whim and fantasy). It led to the publication of Oaxacan Wood Carving: The Magic in the Trees, 0811802507 again with Barbash doing the text and Ragan the photographs. This book is still in print and can be purchased through Amazon.com.

Two year later, the couple moved to North Carolina. In 2004, they decided to re-visit Oaxaca and interview the artisans they had been in contact with fifteen years earlier. The idea was to do a sequel to their previous book. What they returned to was a landscape in transition. Many of the carvers were gone – headed north to the United States in search of a better life for themselves and their families.

They walked into a phenomenon that is happening throughout Mexico. There are many villages today that are primarily populated by women and children, and those too old or infirm to make the journey north, a journey which is all too often iffy and fraught with danger.

Ragan and Barbash have done an excellent job of bringing this heartbreaking exodus to life. Families and individuals they had photographed fifteen years before are photographed once again – now older and more aware of the outside world. The quality of life is a bit better. Both text and photos tell the story. Some of the subjects have cars or trucks. Homes are being built with solid walls and roofs. Children have computers and are more likely to stay in school with the help of the American dollars coming down from the north.

Few of the mojadas (illegal workers) want to remain in the States. But they are disillusioned with the slow progress and corruption in their villages. They’re a generation sacrificing themselves for the future of their children and something a bit better for themselves. It is evident that there is no other way for these poor villagers to make a better life. Many of the older generation don’t understand why, while others do, and are sadly resigned. Most of the younger are “itching” to get away – to get somewhere – to move ahead.

But in this striving for a better life, the “good,” too, must be sacrificed – the sense of community where families cooked together, gossiped together, and sat together at mass, the elderly living with family until they died. They had little monetarily but they had each other. And for good or bad, you can’t stop progress once it gets its foot in the door. As Catalina Julian, one of the younger generation whose photographs appear in the book – as a little girl and then as a young adult – says, “You can’t isolate yourself. Modernity arrives and replaces what you have. You have to adapt.”

All in all, Barbash and Ragan have put together a sensitive and compelling book. Ragan’s juxtaposition of earlier photographs in relation to the more recent ones brings an urgency and a humanity that complements Barbash’s words. It’s definitely worth reading.

The book, a hardcover with the photographs beautifully reproduced, was published by the Museum of New Mexico Press.

Changing Dreams: A Generation of Oaxaca’s Woodcarvers is available from Amazon Books: Paperback