The Months of Mexico

There is magic in the wind and change in the air.

The historic pueblo of Alamos, Sonora, like most Mexican silver towns, has descended to bust from boom more than once in its fitful existence. As long-suffering as a campesino, the community nevertheless has survived those roller coaster rides.

Craggy hills clad in variable foliage – khaki grey in winter and surprisingly green in November after the rains of summer – surround this quiet place where in 1684 its pioneers first plunged their picks into the rock faces, scrabbling for silver. The silver mostly is gone and today the town struggles to survive from season to season with an economy that depends on agriculture – and therefore on rain. Sometimes the rains come as hoped for, often not. Sometimes there is too much.

On Oct. 12, 2008, as the town slumbered, the pitter-patter of a gentle shower dimpled the dust of Alamos. While the 6,000 souls slept, in the hills black, roiling clouds burst open and filled the arroyos with water. With the floods came the winds of Hurricane Norbert, which seemed perversely to have targeted Alamos, bypassing as it did other communities of Sonora as it swept across the Sea of Cortez and bulldozed inland in a searing swath to slam into Alamos.

On that dreadful night, the water cascaded down the mountain sides, redefining every modest channel into a conduit for a churning torrent. The floods of Arroyo Aduana, which most months is a dry, sandy depression where cars and people cross to and fro, tore into the streets and houses, rousing the panicked inhabitants who fled to rooftops and high ground.

Four people perished, 95 homes were destroyed and even today, weeks after the calamity, some old people are succumbing to the trauma, belatedly but irrevocably raising the death toll.

Stout concrete walls were knocked down, cars and trucks were jammed into trees, furniture and personal possessions, instantly transformed into useless detritus, were somersaulted down the streets, and tons of mud and sand clogged many of the avenues and alleyways. Hundreds of people lost their possessions, suddenly finding themselves having to start from scratch without any resources immediately at hand.

“It was a disaster,” said Juan Vidal Castillo, the author of a history of his town, Alamos por los siglos de los siglos (Alamos for the centuries of the centuries). “It was 10 minutes of destruction. Not for 145 years have we seen such devastation.”

I met Vidal Castillo in his crowded and cluttered office where there was just enough room in the cramped space for a workable congruence of modern and pre-modern furniture and equipment. It was one of several similar cubicles lining the outer walls of the historic Palacio, located on a venerable and busy street whose huarache-burnished cobblestones separated the municipal hall from the towering Cathedral of Alamos.

Intense and direct, Vidal Castillo is the registrar of births, deaths, marriages, divorces and other milestones in people’s passages in this timeless place. This agreeable minder of minutiae speaks passionately about his town, expressing without superfluous articulation his love and commitment to Alamos, yet with a steely resolve that it is a place with a hopeful, if uncertain, future.

We chatted with the clatter of a typewriter in the background where his secretary tap-tapped commonplace statistics that, while mundane, by their nature provide skeletal perimeters to the soul of a proud community that seeks to restore its stature. She, too, lost all her possessions in the deadly cascade of water.

Alamos was bred of silver and gold, one of several significant Mexican mining centres that sprang up from the citadels of greed that pervaded early Spanish exploration. Founded in 1684, just one year after its neighbour, Aduana – which faded immediately from prominence – Alamos rose to become the cultural, economic and spiritual centre of this splendid landscape of swooping, verdurous hills and sky-thrusting crags of rock. Farms and cattle ranches are tucked into the valleys and slopes under the shadows of the Sierra Madre Occidental range, where silver must lie buried still. Amidst revolutionary turmoil it would become the springboard for migration westward, sending forth the reluctant founders of important Sonoran centers such as Navajoa and Obregon. These events occurred during conflict between the republican Benito Juarez and the imperialist Maximilian. Alamos became a divided society in the 1890s when revolutionaries and Indians drove out the rich and burned their haciendas, sending them off to invest their salvaged wealth in lands to the west.

The pueblo was devastated. “Ten thousand people left,” said Vidal Castillo. “Alamos almost disappeared.”

Today another exodus threatens the viability, if not the existence, of the community.

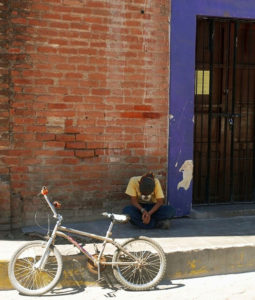

Vidal Castillo points out that the demographic today is primarily among the teenage and 20-somethings as the town continues to struggle to support its people with hard to find jobs and long-term security.

Tragically typical of the diaspora that afflicts countless Mexico towns and villages, Alamos has been drained of its people. They depart in the time-honoured journeys in search for opportunity. Theirs is a stoic response to the reality of poverty, to the need for survival and to reach out to the dreams of the future. It also is a retroactive dreamscape of their fathers, their families, their past. Among the multitudes in Mexico this is an eternal quest, like a thirst unquenchable.

“Adults leave to find work,” said Vidal Castillo. “Young people also leave, when they are able.” There may be a portent to the future of Alamos in the fate of the cottonwood trees, after which Alamos gets its name. They are disappearing as well, for reasons as diverse as the march of “progress” to some persons’ distressing allergic reaction to the pollen. They are still around in diminished numbers, and probably will continue spreading their roots in the sandy soil as they have for millennia, taking hold for future generations.

Indeed, there is magic in the wind and change in the air. As it reaches out for solutions to the survival stalemate, immersed in the push and pull between poverty and prosperity, the town is getting assistance to enhance its tourism potential. It has been named a pueblo magico and is in line for a declaration by UNESCO as a world heritage site.

By the nature of its colonial architecture and natural amenities, it has much to offer.

Alamos is a year-round tourist destination for Mexican nationals and is enjoying growing interest from more adventuresome Americans and Canadians heading south to the sun. About 400 homes have been built or renovated by these newcomers who typically occupy them during the winter, those wonderful months of Mexico that beckon to the snowbirds of North America.

A big attraction for Mexican and foreign tourists alike is the usually benign weather, at an elevation of 1,245 feet, which in the winter offers cool evenings and pleasant days. In the summer the heat is moderated by occasional rain storms in July and August. There are about 360 days of sunshine to assure the visitor that almost any time is a good time to come.

Before taking on its present name, the town was known as Real de los Frailes (the friars), New Spain, so called because of the jagged, triple-peaked los frailes crags which dominate the skyline on the 35 mile (50 kilometre) drive from Navajoa through which the traveler passes on the way south from Nogales to Mazatlan.

The wealth of neglected colonial architecture received a boost when, about 1940, Canadians and Americans discovered the town which then was mostly in ruins. These new inhabitants represented another lode of silver and “white” gold that rejuvenated the town by way of purchasing building supplies and employing local craftspeople to renovate the old mansions.

The visitor strolling the cobblestone lanes observes street after street of colonial splendour, a mosaic of historic structures, soaring portals, grand entrances, splendid carved wooden doors, well-worn stone steps, the grand old palacio, a fine public square and in the center of town, the massive iglesia which, it seems, stands tall as the hills around it.

Author Juan Vidal Castillo, who knows his town better than anybody, probably could talk for days about the culture with its foundations in the Church, the conflicts which emptied the town, the drain of youth fleeing toward surcease of poverty or at least to aspire to achievement, of the military revolutions of the past and the tortuous social revolutions of the present.

Yet, the aspirations of the Alamos of today aren’t so different from the hope of yesterday.

It still comes down to rain. And to the soil nurtured by the skies.

Agriculture, says Vidal Castillo, still represents the future of Alamos. Tourists come for a day, cattle are forever. And, of course, there is hope always from Mexico, the capital, where the vaults are. The federal government is beginning to recognize that Alamos is one of the precious jewels in the great crown of Mexico, one of the few gems high in the hills of silver, surrounded by cactus, subtropical forest, deciduous habitat and a diversity of birds and animals. He is optimistic, especially with plans in sight for a dam that would provide stability to the agriculture base.

And that surely will bring good fortune. One hundred and forty five years ago a mighty wind struck Alamos, killing 50 people and destroying 100 houses. The town weathered that storm. And today, in the wake of Hurricane Norbert – an improbably named Mexican storm which wrought most of its damage in its charge from the tops of the mountains which cradle Alamos – it is time for a fresh start.

Vidal Castillo, the optimist, is confident that the outlook is good for an upswing in the fortunes of a town which has had its share of downers.

All of Alamos looks ahead for gentle winds and good times.