Mention the name “Sean Flynn” to any savvy tween and the recognition is instant: “He stars in Zoey 101.” Indeed, the teenage actor, grandson of Australian-born screen legend Errol Flynn, is more than recognizable to legions of young Nickelodeon viewers. However history buffs, especially those cognizant with the Vietnam War, might associate the name with Errol’s son, an enigmatic combat photographer who vanished in Cambodia in 1970 along with fellow journalist Dana Stone – presumably captured by communist guerillas. He was 28 at the time. Flynn was believed to have died a year later; he was declared legally dead in 1984.

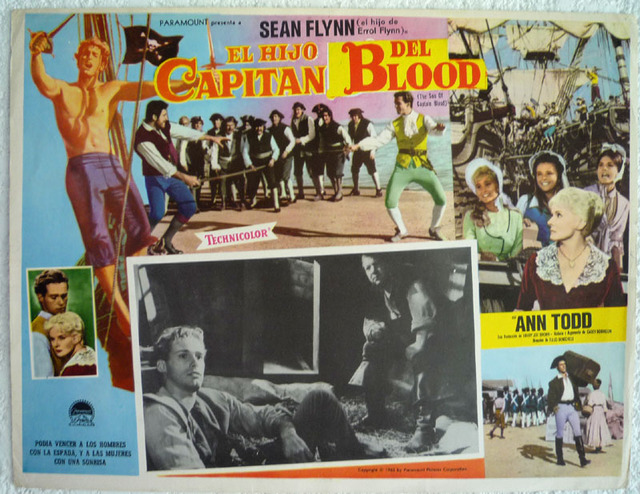

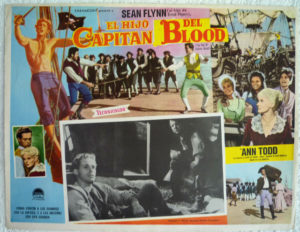

In terms of looks, Sean Flynn was a chip off the old man’s block, and indeed tried his hand at acting, starring in a series of forgettable movies that now seem to take on an almost mythic quality of their own – most (or least) notably The Son of Captain Blood, a film shot in Spain in the early 1960s; along with a handful of others (including a couple of Spaghetti Westerns). Flynn quit acting, and after a series of adventures worthy of his old man’s wicked, wicked ways, landed in Vietnam to photograph the war.

Since being immortalized in song by The Clash, in writing by Michael Herr (Dispatches), and in film (by Dennis Hopper in Apocalypse Now – if only in part, and a broad interpretation, to be sure), Flynn has come to exude the qualities of an enigmatic cult figure, since for many people that’s precisely what he is. Imagine the thrill, then, to find a series of well preserved Mexican-made lobby cards of young Flynn in The Son of Captain Blood (El Hijo del Capitán Sangre) in a small (almost hole-in-the-wall) secondhand bookstore in Mexico City – which is what your humble correspondent did quite recently and yes (in case it hadn’t occurred to you), your humble correspondent is a Sean Flynn fan.

But this story is about lobby cards, and the joy of collecting them, particularly in Mexico City – where they are, as a rule, cheap as chips.

What, precisely, is a lobby card? Well, it’s like a movie poster, only much smaller. They are usually around 11 x 14 or 8 x 10 inches and obviously designed to promote the advertised film. The smaller version is also known as a “still” or “front-of-house” card, and briefly summarizes the movie in a series of captioned scenes. However, Mexican lobby cards are larger than the U.S. version – at 13 x 17 inches, and are regarded as a cross between a jumbo lobby card, title card and one sheet poster. Lobby cards come in sets that range from three up to 20 – although it is fairly typical to simply come across one, and for framing purposes, one should be enough.

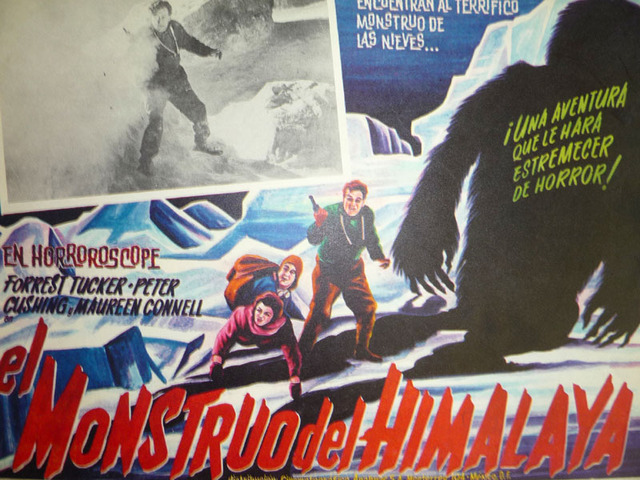

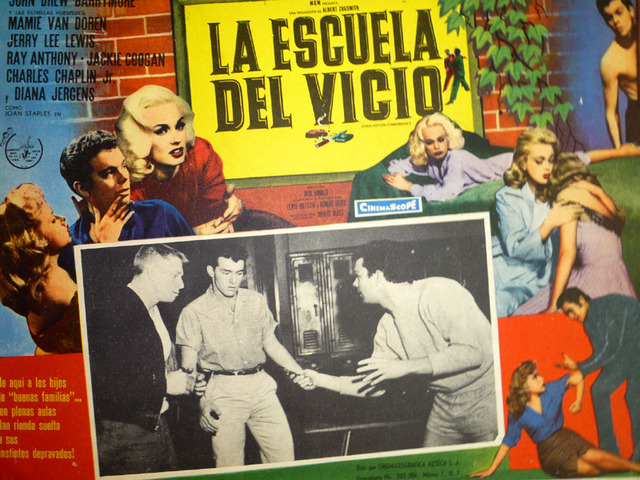

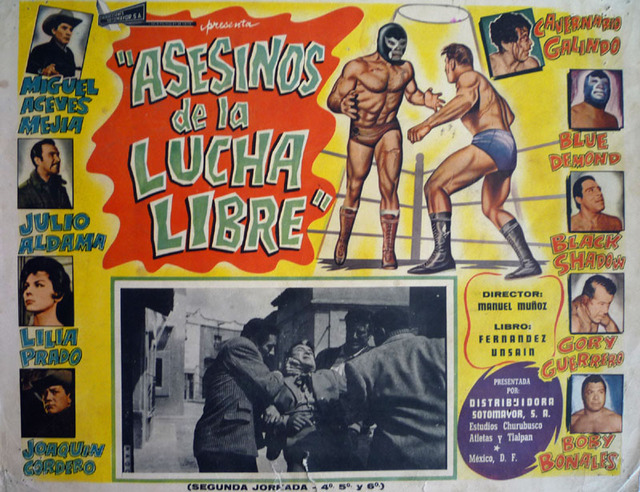

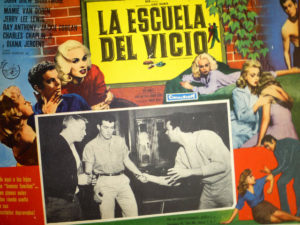

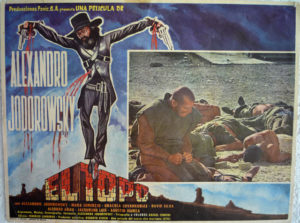

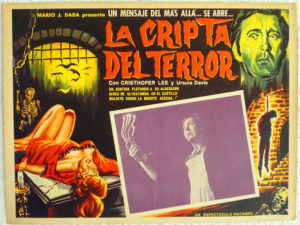

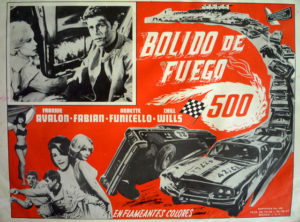

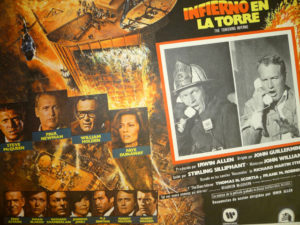

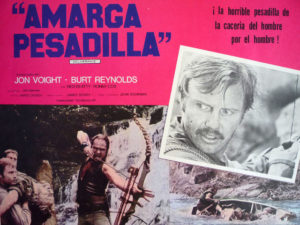

Lobby cards first appeared in the United States in the early 1910s. They were ostensibly designed for display in a cinema’s lobby, the way the large format movie posters have done so exclusively since the 1980s, when the use of lobbies cards was discontinued (at least for the U.S. market; some other countries soldiered on with them). Mexican lobby cards were produced by local graphic artists and tended to be much more artistic, colorful and lurid – utilizing such tools as painting, photo montage, drawing, dramatic comment and an inset black-and-white still from the film.

According to collecting experts, Mexican lobby cards of U.S. films are rarer than U.S. lobby cards of the same since fewer of them were printed, due to the fact that Mexico had fewer cinemas, and distribution was somewhat less of an American style military campaign in terms of publicity. Be that is it may, the term “rare” is wholly relative: most sellers of Mexican lobby cards on sites such as eBay can’t, it seems, give them away much less sell them. No one seems to have cared for them before, and in the current economic climate, most no one cares for them now. One should not have an end game in mind that lobby cards are somehow, or somehow will become, “collectable” (read: profitable). No, Mexican lobby cards should be sought after simply to enjoy as examples of a bygone era when kitsch ruled the cultural waves.

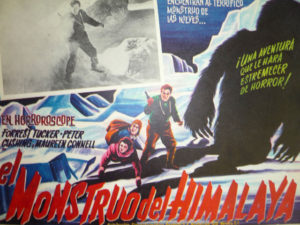

Mexican lobby cards wallow in exploitation, indulging in as much sex and violence as their respective eras legally allowed. Vampires are vampires. Aliens are aliens. Babes are babes. Criminals are criminals. Abominable Snowmen are Abominable Snowmen. Krakatoa is still East of Java (even though it’s west) and will remain that way for all eternity.

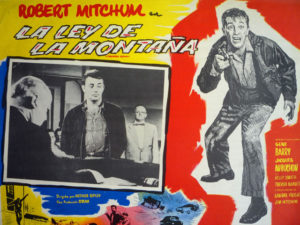

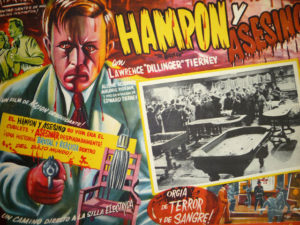

Perusing through some of my own titles, all the characters, concepts and worlds imagined come effortlessly to life through the art: a hanged man and a damsel in distress, Christopher Lee in full fright (The Crypt of Terror); the mystical renderings of Alejandro Jodorowsky’s cult classic El Topo (the director’s first name is inexplicably spelled with an “X” on the poster); Lawrence “Dillinger” Tierney presenting a visage of glowering menace in The Hoodlum; Dick Contino, Mamie Van Doren and Louis Armstrong as hipsters (with guns) in Albert Zugsmith’s The Beat Generation; Robert Mitchum, by turns laconic and desperate, in Thunder Road; Mamie showing her best side again in High School Confidential….

Top line cartoon and caricature art can be found in certain lobby cards from the 1950s that showcase the work of Ernesto García Cabral (nicknamed Chango) – also known as “The Greatest Cartoonist You’ve Never Heard Of.”

Garcia studied art in Paris in the years before World War I, and became well known there as a cartoonist. Returning to Mexico in 1918, he became one of Mexico’s greatest illustrators, known for his bold colors, dynamic designs and, later, his expressive caricatures in lobby cards of such comedic legends as Cantinflas, Tin Tan and Resortes in films such as Rumba Caliente (1952); Qué Lindo Cha Cha Cha (1955); Resortes Hora Media de Balazos (1957); and Las Carinosas (1958).

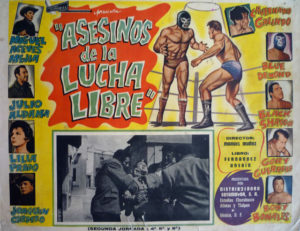

More homegrown products to enjoy include the legendary heroes of Lucha Libre: those uniquely Mexican wrestling creations who shifted their considerable weight from the lucha ring to the silver screen, and the accompanying lobby cards for their unabashedly shlocky movies are quite often classics. One of the first to get behind the cameras was Wolf Ruvinskis – aka Neutron – followed by Blue Demon, Mil Máscaras, Huracán Ramírez and, of course, El Santo. The Saint led the way in countless films (and gracing lobby cards) driving a white Aston Martin, fighting crime between wrestling gigs, and working from his own laboratory (not unlike Batman).

Unlike film posters that are really big, take up heaps of wall space and are super expensive to frame, lobby cards are small, cheap to frame and do not take up much wall space. The lobby card represents economical art to mount in every way. They are more easily found (at least in Mexico City) than their ostentatious poster counterparts, obviously in such places where they take up little space: in the far corners of numberless secondhand book stores, anchoring a mat on the sidewalk stalls of flea markets, in various antiques and memorabilia shops – and you shouldn’t have to pay more than 10 to 15 pesos for any one of them (unless it’s quite a rarity, or sold as part of in a set).

Happy hunting.

Lurid is mostly right, especially for the horror and more primitive art-styled lobbies. If you’d like to see more Mexican lobby cards, and some are quite exquisite, click here.