Approximately twenty-five years ago I heard rumors of some curious geological formations hidden high in the hills above the town of Ahualulco de Mercado, which is located about 58 kilometers west of Guadalajara, Mexico’s second-largest city. “There are giant stone balls up there,” I was told, “perfectly round and lying in a great bed of volcanic ash.” When I asked how these megaspherulites (as scientists call them today) came into being, I was told that they had been shot into the air from inside Tequila Volcano and had fallen to earth, all of them landing inside a circle less than four square kilometers in diameter.

Parts of this story were hard to believe, so naturally, I wanted to see for myself and eventually I set out for the Piedras Bola guided by a ten-year-old boy from Ahualulco. Well, I don’t think I would have accepted such a young guide if I had known I’d be hiking for over three kilometers, often with no clear trail to follow. Amazingly, my youthful guide only got us lost once and I had an opportunity to see the stone balls in the raw, so to speak, before any of them were attacked by graffiti “artists.”

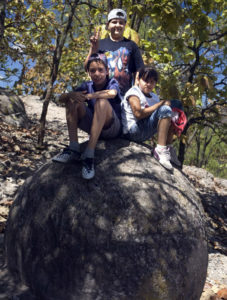

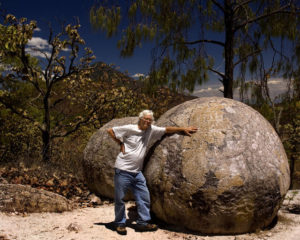

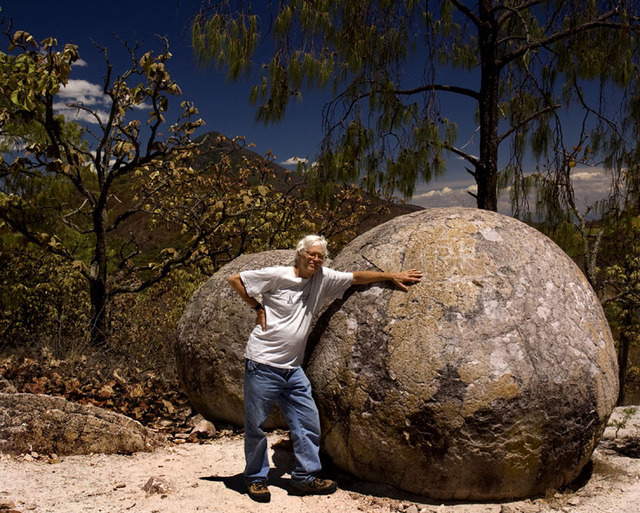

Most of the stone balls I saw ranged from one to two meters in diameter, many still half-buried in volcanic tuff, and, yes, a great many of them were very close to spherical. As Tony Burton stated in Western Mexico, a Traveller’s Treasury, “Nothing quite like them exists elsewhere in Mexico or, according to current scientific opinion, anywhere else in the world.”

Discovery of the Piedras Bola

It seems this area first came to the public’s attention thanks to Robert Gordon, director of the Piedra Bola silver mine. The mine was named after a large round stone ball that stood near the entrance. In 1967, after his retirement, Gordon began a search to see if there might be other such balls in the area and soon found six more giant spheres approximately two kilometers from the mine. Gordon then sent photos of his discovery to famed ethnologist and archeologist Matthew Williams Stirling, who had described spheres beautifully worked by pre-Columbian natives of Costa Rica. In short order, 17 other stone balls were found in the hills between Ameca and Ahualulco, most of them around three meters in diameter.

Next on the scene came USGS geologist Robert L. Smith leading a National Geographic-Smithsonian expedition in 1968. The following year an article appeared in the August National Geographic and the Piedras Bola gained international fame. The article refuted the idea that the giant balls may have been crafted by human hands and put forth the first of several scientific theories on how they came to be.

Origin of the megaspherulites

The National Geographic theory is summarized by Tony Burton and visualizes the balls forming by crystallization of hot ash around nuclei of lava fragments, producing boulders of rhyolite.

Smith’s hypothesis seems to have been rejected by the University of Guadalajara (UDG)’s Arturo Curiel Ballesteros in 1998. Instead, he proposes that the megaspherulites formed in the sky, assumed a round shape while falling and retained this shape because they fell into a soft, hot bed of ashes.

In 2007, the UDG appears to have abandoned Curiel’s theory in a 266-page book dedicated to the Piedras Bola and their environment and bearing the weighty title, Gestión para la sustentabilidad del area natural Piedras Bola Ahualulco de Mercado, Jalisco (ISBN: 978-970-27-1177-3) by Carla Delfina Aceves Avila et al. For the sake of brevity I will refer to this publication below as “the Bola book.”

The Bola book has six authors, seven collaborators and two coordinators, so it is difficult to know whom to credit or blame for the 21-page “Analisis del origen de las megaesferulitas” which it contains. This explanation states that while covering a distance of some three kilometers, the pyroclastic flow picked up volcanic bombs or incandescent blocks of various sizes which began to rotate as they were pushed along, finally acquiring a spherical shape. It is also conjectured that “mini-spheres” may have formed around small clusters of crystals in the flow and likewise began to rotate, later contracting to form individual bodies.

The age of these great balls is also a matter of controversy, with estimates ranging from 40 million years before present to less than ten million years.

Among the pages of the Bola book are recommendations for development of this unique area in an ecologically friendly way. Surprisingly, this plan was immediately put into action after the book’s publication and, in less than two years, more than ten million pesos were spent by the Jalisco Secretariat of Culture to create an infrastructure that might someday turn this remote site into one of Western Mexico’s biggest tourist attractions.

Hiking to the great stone balls

I was not really sure I wanted to see the new Piedras Bola park, as I had been quite satisfied with the site as it stood years ago, but one Saturday in May, 2009, I set out for Ahualulco with my wife Susy and our friend Mitch Ventura who had recently returned from fighting fires in Iraq. “This won’t be as exciting as strolling around Baghdad,” I told Mitch, “but your chances of survival are a whole lot better.”

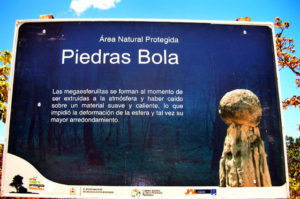

As we passed Ahualulco along the highway from Tala, we saw a prominent sign announcing the Piedras Bola. We turned left onto the scenic road to Ameca and 13 kilometers later came to a rather sparse parking area at the trailhead. Several signs told us all about the Piedras and the surrounding area, but failed to mention a word about how long a hike was ahead of us.

To my amazement, a sign purporting to explain the origin of the great stone balls quoted Curiel’s “they-fell-from-the-sky” theory. I suspect the sign-maker, when he consulted the Bola book, had been daunted by the 21-page, 21-diagram explanation and had assumed – with a sigh of relief – that the three lines by Curiel were a summary of the book’s new hypothesis. Fortunately, the book doesn’t mention legends about the stones having been carved by the gods or I’m sure that’s what would be on the official sign explaining the Piedras to Mexico and the world.

The steep, narrow path of the old days has been replaced by a less aesthetic, but easier-to-negotiate stone stairway which brought us up to a wide, flat, dirt road heading uphill in both directions. Here’s a spot that really needs a sign, but there is nothing telling you which way to go. Fortunately, a family came strolling along this road at that moment and told us that turning left would take us back to a second parking area on the highway, one kilometer south of where we left our car. We learned that the second car park is for mountain bikers and horseback riders and that the “road” we were on is actually an unusually wide biking, hiking and equestrian trail.

This luxury “path” is just over six kilometers long with a vertical difference of about 123 meters. Along the way to the Piedras Bola you may come across some of the 107 species of birds found in these rugged hills and if you wander off onto one of the side trails, you may spot the tracks of puma, mountain lions, wild boars or white-tailed deer. To me this route still felt a bit too much like a road and not enough like a trail, but it definitely has some fine lookout points with dramatic views.

Bicycle riders will probably be delighted with what they find. Except for the grade, this smooth road is easy going; in fact a sign indicates this is a good route for beginners. All of us disagreed with this assessment after coming upon a couple of steep, tight curves where junior could easily go flying off the edge of the road and down a two-hundred-meter drop.

Zip-lines and a wobbly bridge

Speaking of dangers on this trail, you’ll find two brand-new zip-lines along the way. These Tyrolean crossings are unmanned and just begging some daredevil to try traversing them sliding along on a belt or handkerchief, as demonstrated by the stars of countless adventure movies. One of these steel cables measures 330 meters in length and I can imagine how it would feel to be stuck in the middle of it, hanging in empty space. The same can be said for a long, wobbly 12-centimeter-wide suspension bridge which is clearly meant to be crossed only if you are wearing a harness and clipped into a cable above your head. This bridge is also openly available to anyone who comes along and may prove irresistible to some hyperactive youngster (or adult, for that matter). There’s not even a sign stating that the zip-lines and bridge are extremely dangerous when not used properly.

At last, after an hour an a half of walking, we reached the end of the road and came to a pond and a small outdoor amphitheater decorated with a couple of the smaller stone balls. Although the Piedras Bola are located still farther uphill, we noticed that for some exhausted hikers, this was the end of the line.

We, however, stoically carried on for another 400 meters, arriving at an altitude of 1908 meters where we found ourselves surrounded by the venerable spheres, some of which were over three meters in diameter. So far, the bed of tuff in which they lie has not been “developed” in any way, so if you want a good look at these truly impressive giant stone balls, you still have to wander about on the hillsides, looking for them.

A catalog of giant balls

Burton mentions more than 150 Piedras Bola but the UDG has catalogued only 72 of them, listing each ball’s coordinates, size and condition. Surely there are many others that escaped the researchers’ notice, not to mention all those that are just below the surface, about to be uncovered. As a matter of fact, I long ago ran into two stray balls 4.7 kilometers north of the official site, alongside the road to the old Amparo silver mines. Who knows how many other balls lie along that stretch?

Only after our visit to the Piedras Bola did I discover – to my surprise – that the Bola book lists 26 of the balls as having a diameter of six meters or more and states that the biggest Bola of all was measured at a whopping 9.5 meters wide. This is ball number 36, which of course we did not see, but whose location is given at the end of this article. Without a doubt, I must return to the Piedras Bola to feast my eyes on this monster.

Something else we missed on our visit were the torrecillas, tall columns of tuff, each supporting a single stone ball. You have to follow poorly marked trails for around 1.5 kilometers from the amphitheater in order to see them.

Throughout the Saturday we spent at las Piedras Bola, we saw only 20 other visitors and not one of them had brought a boom box along. This was surely thanks to the five-kilometer hike required to get there. So, for the moment, this is probably one of the few tourist attractions in Mexico likely to be half-deserted and quiet even on a Sunday.

Though we may never know for sure how the Piedras Bola came into being, they are one of Mexico’s – and the world’s – most curious natural wonders and well worth a visit.

How to get there

From the Guadalajara periférico or ring road, take highway 15 (Nogales and Tepic) 25 kilometers to highway 70, which heads southwest towards Ameca. This is only accessible from the libre, so don’t get on the cuota (toll road). Go about 17 kilometers until you come to the big sugar refinery on the road at the Tala turnoff. Continuing towards Ameca about 1.5 km, turn right onto the road heading for Teuchitlán and Ahualulco. From this turnoff, it’s 27 kilometers to Ahualulco. Just past the town, turn left onto the scenic highway to Ameca.

Drive 13 kilometers to the hikers’ parking spot at 13 Q 600865 2283421 (GPS UTM coordinates with WGS84 datum) and climb the stairs. If you have a bicycle or a horse, drive another kilometer south to the second parking area and start up the wide “trail” which ends at the amphitheater.

Walk another 400 meters north to find the stone balls scattered round about 13 Q 598199 2284120. The biggest stone ball, according to the UDG, is right in this area at 13 Q 598163 2284135 (if they were using WGS84 as a datum, which is not mentioned).

The drive from Guadalajara to the parking area takes about an hour and the hike about an hour and a half (if you do nothing but walk). Bring along plenty of water.