Most modern art aficionados know that if mysterious British artist Banksy didn’t create the urban world’s love affair with quirky riddles in stencil art on public walls, then he certainly spearheaded its emergence into light — at least from a broader (if somewhat bemused and undecided) public’s point of view. Those in the know will cite Blek le Rat, Jef Aerosol, John Fekner, Above, and Shepard Fairey before he leaped into the public consciousness with his multi-toned Obama portrait. Yet Banksy’s various museum pranks in the recent past have helped bring to notice his work in graffiti stencils, which are celebrated for their brilliance and humor.

A stencil is a template created by removing sections of transparent plastic sheet or piece of cardboard in the form of an image (or text) creating a physical negative. A quick reproduction of the image on a (generally walled) surface is achieved by applying spray paint across the template. Its earliest historical permutation can be linked to cave painting, when ancient man sprayed pigment around his hand to create print outlines or utilized a hollow bone to direct pigment to produce depictions of animals.

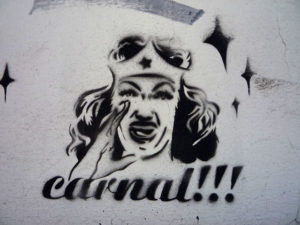

Technically, street stencil art is also illegal, but no one can deny its cultural significance and the fact that it has become a phenomenon from its early beginnings in such faraway places as Melbourne, Australia. It has taken off in Mexico City, too and, like Banksy and many other street artists, the talented exponents of this form are largely unknown creators who have adopted obscure aliases, reveling in cult anonymity.

Most stencils in the D.F. are not on the same ambitiously large scale of a Banksy; nonetheless such nifty night operators as Cardoso, Tenoch Powers and Mother Monkey Collective are producing quality stencil art, and the upmarket “Bohemian” district of Coyoacan is a good place to check them out.

Mother Monkey Collective was formed in 2007 and now consists of six persons. Founder “Madres” (“Mothers”) says the collective takes a whimsical approach to leaving its mark on the city.

“The idea of going out to the streets to do what we do was born out of the joy to show what we had inside our heads,” Madres says. “We did not want to denounce or protest anything. We started to see that in the city there are many ways of expressing yourself. Some good, some bad, but that’s the way it is.

“I do not consider that what we do is professional. We paint what we feel,” Madres adds. “We don’t expect people to have any reaction; nevertheless, this does happen and it’s good, like leaving your mark on the city, marks that appear and disappear.”

Speaking personally (and as a past native of Melbourne, where the movement largely rose to prominence), to search for, find and photograph evidence of this artistic subculture has taken on the sensation of a treasure hunt — spotting a stencil on a wall carries with it a “collectible” buzz. Plus the work is generally of a very high quality.

Some recent Mother Monkey Collective projects include a “guerrilla”-style campaign for the U.S. photographer David LaChapelle, who recently staged an exhibit at the Colegio de San Idelfonso of works from his new book called Heaven in Hell. A small publicity agency (that shall remain nameless) proposed the guerrilla advertising campaign to Mother Monkey Collective to promote the show.

The result was some very interesting stencils.

Stencil artists remain an elusive lot, and — like many graffiteros — seem to gleefully eschew the trappings of publicity, the seeking of fame or (obviously) any hope of making money out of their work — at least in the short term (indeed, stencil projects indicate “long term” in every sense). Stencil artists reject the notion of creating art for any other purpose than as an end in itself, in comparatively similar measure to the way in which the hipster hoboes of the Beat Generation took to the road for no other purpose than to “move.”

“I think that what inspires us is our environment, everyday life, situations we bump into, characters we know,” Madres says. “Something important is to see the number of urban artists who are emerging day by day, not only in this city but all over the world. It is interesting to see the way they express themselves. I think that is a great motivation.”

The generally accepted notion of achieving success in the field of graffiti art is not one these artists generally adhere to, or seek, despite its increasing legality resulting from public and private commissions. Yet the notion of “respectability” is on the rise.

“One day we sent some stencils to a contest in a magazine, did well, and got invited to the Centro Cultural España de la Ciudad de Mexico to paint,” Madres says. “Little by little, our pieces started to be noticed and a series called Lo Que Nos Dio Sentido (“What Gave Sense to Us”) was born. For the moment we are working with small walls, stickers, stencils of characters that come to mind. The point is to not stop.”

Related articles on MexConnect

- Graffiti: the Estadio Azteca and Mexico City’s new wave muralists

- Graffiti: Mexico City’s wall art emerges from the shadows