All the world has been told that tequila, the drink was born in Tequila — the town located 45 kilometers northwest of Guadalajara — but is this really a fact? Curiously, the famed Tequila Express train has, for years, been carrying tourists straight to a small town called Amatitán, and not to Tequila at all.

This piqued my curiosity and, hoping for illumination on the proven origins of Mexico’s most famous drink, I consulted the Jalisco Secretariat of Culture’s Guide to Agave Country. It states that the first distillery or taberna was established at the end of the seventeenth century on the property of the Hacienda de Cuisillos. This particular “rancho,” however, apparently stretched all the way from Guadalajara to the slopes of Tequila Volcano, offering little indication of exactly where that first taberna might have been located.

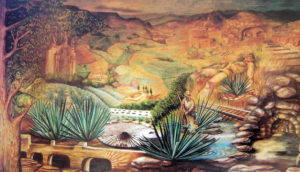

Finding the first distillery looked just about impossible, but then I came upon a plaque recently erected by the tequila producers at a newly constructed belvedere overlooking Santa Rosa Valley, which lies only nine kilometers north of Amatitán. This plaque states that the oldest taberna of this region was located in nearby El Tecuane Canyon and that it was a most unusual operation indeed. It supposedly utilized both pre-Hispanic and Hispanic brewing techniques, and cleverly took full advantage of gravity and a nearby spring to carry out its procedures.

I found several volunteers who, like me, found all this very interesting, so off we went to look for the ancient taberna.

The cobblestone road to Tecuane starts about five kilometers north of Amatitán, with a primitive sign announcing “Balneario.” The unpaved road is in great shape, but bumpy enough to warrant a high-clearance vehicle. We drove about a kilometer and suddenly found ourselves overlooking a huge canyon we had never seen before. The view was absolutely staggering. In some other parts of the world, hotels and restaurants would have been constructed in a place like this and tourists would come from far and wide to gaze upon this multicolored panorama, a magnificent patchwork quilt created by Mother Nature herself. The road to El Tecuane, however, seems to be known only to local people and the only way to see it is to creep along a very, very narrow, single-lane, cobblestone road with one eye on the stupendous view and the other on the edge of the terrifying, sheer drop right next to you. If you happen to meet someone coming the other way, a great song and dance ensues as one of you attempts to back up without sailing over the edge.

Luckily, the cliff-hanging ends after another kilometer and you can breathe easy while driving a further two kilometers down to old El Tecuane Taberna. This historic site — which goes back to the early 1700s — is fenced and locked up, but (after three separate attempts, I might add) we found the man with the key, Don Rosario Villagrana, at huge, modern Santa Rita distillery, located just above the old workings.

As we made our way down the road to the old taberna, we asked our guide whether it was true that the famous tequila agave originated in Santa Rosa Canyon. “No, that’s not so,” he said. “The blue tequila agave actually comes from this very valley, right here.” So it seemed we had come to exactly the right place in our search for the origins of Mexico’s national hard drink.

Don Rosario unlocked the gate and we walked to a wide, flat spot where we peered down into the kind of oven used by the Indians to cook agave cores or piñas before the Spaniards arrived. This is a deep pit lined with volcanic rocks. The Indians used to throw a mixture of piñas and red-hot rocks into this pit and then cover it up. We were told this is the only taberna in existence with an oven that was heated from the inside, a system commonly used in pre-Hispanic times for cooking soups, mush, etc. and also for heating temazcales (sweat lodges).

Once the mezcal had been roasted, it was then crushed using a people-powered millstone which was rolled around a sunken circle whose floor was lined with blocks of basalt. Numerous worn-out millstones lay all about the place, suggesting that this taberna had been operating over a very long period.

Next, the sweet juice trickled downhill to a lower mesa in which 44 fermentation pots were carved into the living rock. Each of these held about 3,000 liters. This kind of rock is called tepetate, which is a soft, yellowish-white conglomerate mineral composed of siliceous particles. It is said that this rock actually promotes fermentation, although it must have been a rather slow process. However, carving the pots in the rock had a big advantage: it allowed native people to brew their drink in large quantities. Clay vessels would not have withstood the pressure of 3,000 liters and barrels with hoops could not be made because in pre-Hispanic times, metal-working was unknown.

Don Rosario told us the mezcal juice was literally filtered through the porous rock beneath the crushing area, and followed a stratum of harder rock downward to the fermentation area. This was hard to believe and it would be interested to conduct an experiment to see if liquid would indeed travel from the crusher to the pots on its own.

Only when you walk among the 44 huge pots of rock do you really appreciate what a monumental project those Indians had been engaged in and what huge quantities of alcohol they had been producing. Alongside this level of the taberna you can see a big channel which supplied the large quantities of water that had to be added to the sweet juice in each pot.

When the alcoholic brew was ready, it was then carried further downhill in buckets, to yet another flat area where there were several stills, cooled by cold water channeled from a nearby spring via an aqueduct, which, seems to be a European contribution to the process. The lowest level is the only part of the operation which doesn’t look 100% native.

Now, most sources say the technique of distillation was brought to the new world by the Spaniards, but Don Rosario insisted the Indians originally had their own stills, in which the steam was condensed in cloths hanging above a pot of boiling alcohol. “They wrung out these cloths and distilled that alcohol a second time,” and one taste of this potent “vino mezcal,” as it was first known, was, supposedly, what got the Spaniards into the tequila business. It should be pointed out that while vino means wine in Spanish, the word is popularly used in Mexico for just about any drink containing alcohol.

The claim that the Indians had their own technique for distilling spirits is backed up by the owner of Santa Rita distillery, tequila historian Miguel Claudio Jiménez Vizcarra, who has published books and pamphlets on the subject (in both Spanish and English) in an effort to “put a halt to false legends about the origin of tequila.” He points to historical documents indicating that tabernas first appeared in the town of Tequila only in the last third of the eighteenth century, while Amatitán was officially recognized in 1769, by the Royal Court of Guadalajara, as the principal manufacturing center of vino mezcal.

Jiménez Vizcarra goes on to quote from Domingo Lázaro de Arregui’s 1621 Description of New Galicia:

“The Mexcales are much like the maguey. Their root and the base of their spikes are roasted and eaten. In addition, when they are pressed, they exude a must, from which a liquor is distilled, clearer than water, stronger than aguardiente and of such good taste.”

Jiménez Vizcarra argues that “stronger than aguardiente” indicates this drink was a spirit, and “clearer than water” could only have been obtained with a second distillation. Archeologists in Jalisco counter that the Spaniards had been around long before 1621, so this quote doesn’t prove the indigenous people invented distillation on their own.

Whether the native Mexicans had developed their own stills, I can’t say, but standing in the middle of 44 huge old fermentation pots carved out of rock, I was definitely convinced that those Amatitán Indians (Tecuane has always been considered part of Amatitán) were no amateurs when it came to alcoholic beverages.

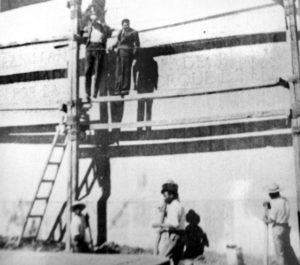

When I discussed the possibility that Amatitán might be the “Cradle of Tequila” with Jorge Monroy, one of Mexico’s leading muralists, he casually mentioned that this town was quite pretty and he had done several watercolors there.

Well, I hate to say it, but the view you get of Amatitán from old Highway 15 — which skirts the town along its northern perimeter — is anything but “pretty” and would lead you to believe that no artiste had ever set foot in the place during its entire (very long) history. About this, I couldn’t have been more mistaken.

One fine day, I invited my sister to join me on an exploratory visit of the place. Right from the start, Amatitán proved to be a bit different. El Centro was not in the center of town at all. Instead, the plaza and church are at the eastern end, at the foot of a steep hill. The reason for this immediately became obvious: the town’s only source of water is here. Originally, this was a spring trickling out from under the hill, but in the 1800s — signs in English and Spanish informed us — the townspeople decided to dig a qanat or underground aqueduct from the plaza to the water table, over 60 meters inside the hill. This was a success and resulted in a large pool of drinking water being available to anyone arriving at the plaza. I was very interested in this tunnel because I had previously explored several other qanats in Mexico and was fascinated with the concept that technology born in the Middle East millennia ago had been carried all the way to the new world by the Spaniards.

Naturally, we went into the Presidencia Municipal — at the other end of the plaza — to find out how we could visit the qanat.

The second the staff spotted two “güeros” (blonds) walking through the door, word was sent to their dynamic Public Relations man, Ezequiel García: “Tourists have arrived in Amatitán!”

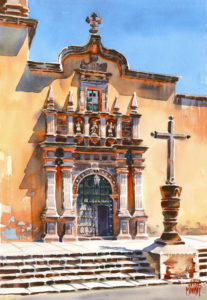

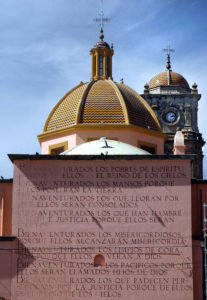

Ezequiel García turned out to be the very person we really needed to see. As we walked across the plaza, he gestured at the magnificent domes crowning the church. “Those were the work of the famed architect, Luis Barragán (considered the most important Mexican architect of the 20th century) and inside the church you can see four paintings by none other than José Clemente Orozco himself.” We also stopped to admire a great wall on which the Eight Beatitudes were hand engraved by… well, I’m still not sure if it was Barragán or that other great architect, Ignacio Díaz Morales, because both of them were responsible for remodeling Amatitán’s magnificent church.

The church, by the way, is closed from 1:00 to 4:30. Once it opened up, we discovered it truly was a jewel, just as we had been told, and, of course, we were finally able to view those celebrated paintings of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. We asked Ezequiel Garcia if he was sure they were really by Orozco. “I wondered about that myself,” he replied, “so I asked our parish priest, who had once been Barragán’s student. The Cura told me that Orozco walked into the church one day with pencil sketches for these paintings. The Pastor at that time was a crusty character who took one look at the sketches and said he’d prefer to see those spaces left blank. Orozco then ripped the sketches to shreds and stomped out of the church. But Barragán was outside working on his Beatitudes. He calmed Orozco down and told him to ignore the Cura and go ahead with the painting, which Orozco then did, without benefit of his sketches.”

Large maps in the plaza show that Tecuane is not the only old taberna in the municipality of Amatitán. There are several others located inside the spectacular canyons carved by the Río Santiago, which are as rich in sparkling rivers as the town of Amatitán is lacking. These canyons would have been ideal sites for illicit distilleries hundreds of years ago when, according to Tony Burton in Western Mexico, a Travellers Treasury, the Spanish authorities outlawed liquor production in Mexico because it threatened to compete with Spanish brandy. “This suppression led to the establishment of illicit distilling in many remote areas, including parts of Colima and Jalisco.” El Tecuane would definitely have to be classified as one of those remote areas and, for the moment, seems, in my opinion, to qualify for the title of The Cradle of Tequila.

How to get to Amatitan

Drive west out of Guadalajara toward Nogales, following “libre” highway 15 west 38 kilometers to Amatitán. As you descend to the town, you’ll notice a cemetery on your right. Across from the cemetery, on your left, is Calle Niños Heroes. It’s the very first street of Amatitán, on the left hand side, so keep your eyes open. Turn left onto this street and it will take you south, 643 meters, directly to Amatitán’s plaza. The driving time from the edge of Guadalajara to the plaza is about 35 minutes.

If you would like to visit El Tecuane, upon reaching Amatitán, turn right just before the first overhead footbridge across the highway. Take this road, signposted “El Salvador,” four kilometers north. Turn right at the Tecuane Balneario sign onto a dirt road. Whenever you see forks or turnoffs, stick to the main cobblestone road. After only one kilometer you will come to the magnificent canyon view. Three kilometers from the El Salvador road, you come to the only major fork in this itinerary. Bear right. After one more kilometer you’ll be at the Santa Rita Distillery and just below, the ruins of Taberna Tecuane. Driving time from Guadalajara to the old tequila workings: just over one hour.