Westwords

School daze is near which reminds me that most of what I think I know about Mexico education is based on second-hand information.

The system is not broken. It never worked in rural communities, out in the country, where so many live near or below the poverty line. There is no yellow school bus, no free ride.

Two presidents, Vicente Fox and Felipe Calderon, in ambitious moments, promised educational reform. Almost everybody agrees reform is needed. Reform is generally interpreted as more spending.

Those who tell the truth admit the education system is some degree of a failure. Oh no, not all of it. There are brilliant graduates of excellent schools, most often city schools in high-rent districts. Some private schools, truly superior, are probably more productive than you-know-who to the north.

The head of the National Institute for Adult Education says a frightening number of Mexicans can’t really read and write and that 45.7 percent are poorly educated. The goal is to reduce that deficiency by 2012. Somebody better hurry.

There is a younger problem. More than half of Mexico’s 15-year-olds are said to be below international standards in basic math and science skills. How can the country expect to compete long-term with better-educated work forces in China and India?

One of the prizes of the revolution, a hundred years ago, was free public primary education, as mandated in article 3 of the constitution. In real life, schools frequently squeeze families for money because, they say, government funding falls short.

Early education is said to be “compulsory” but that means states are compelled to offer it. In most places, youngsters are not required to attend and certainly aren’t forced to learn. One of my best young friends dropped out in fifth grade and now operates a bulldozer. Many dropouts are not so fortunate.

One of my sources, Dr. T. D. Stong, a regular visitor to rural villages (almost half of the Mexican population is rural), says less than 20 percent go past sixth grade and only a relative few make it past ninth grade.

“I have seen no interest by local governments to sponsor skill training so youth can move into jobs instead of toward cities and the Rio Grande. My personal feeling is that, as seen in many developing nations, the rich sense some advantage in maintaining a goodly portion of poor people.”

Poor education is supposedly the root cause of poverty and too much unskilled labor — which results in illegal immigration. Economists would have you believe education reform is the only possible cure, that high fences and border patrols will never do it.

The face of Mexico public education is the teachers’ union, with a million and a half members. The face of the union is president Elba Esther Gordillo. She is strong.

The union is not just a union, it pretty much directs educational policy. That is very good for those on the permanent payroll. Once a school employee gains tenured status, he or she is in for keeps. It is almost impossible to fire such a teacher. Incidentally, tenure can be inherited — or sold.

You can believe this or not but 30,000 union officials are supposedly on the educational payroll as teachers. They do not appear in classrooms.

Elba Esther Gordillo says she favors reform. My buddy Javier says looking to her for positive change is like expecting the fox to coax more and better eggs from the chicken house.

Gordillo was lukewarm on testing teachers to see if they know enough to teach. Many ordinary people were stunned to hear that nearly 70 percent of teachers flunked the first nationwide test to measure basic skills. Those who remember yesterday keep an eye on good, old Oaxaca section 22 and the pattern of teachers’ strikes, on general principles, whether they need anything or not. The union got credit for the angry 2006 shutdown of the city.

All that said and heard, I know this much for certain: good teachers make a wonderful difference.

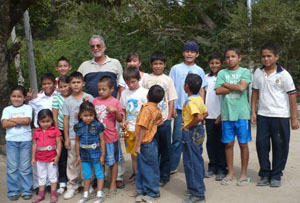

A few weeks ago, I told you about Luis Alberto Martinez Gomez. He was an illegal immigrant who finished high school in California and returned to Mexico with the idea of going to college. He had no money. With smart guidance, he interviewed well for a teaching job, beginning level, go anywhere, do anything you ask. The Tepic district, short on dependable manpower for the inconvenient outback, provided five days of instruction on how to be a teacher and assigned him to a one-room operation in San Quintin.

Luis knew far more than enough to teach his 14 students, ranging from first to sixth-graders. He did much more than the job demanded. The response was

Luis knew far more than enough to teach his 14 students, ranging from first to sixth-graders. He did much more than the job demanded. The response was sensational.

With outside encouragement, gift computers, other resources and a plan to improve the school building, the little community caught on. Parents pitched in. Parents supported the teacher. Attendance suddenly mattered. Children did homework for the first time in their lives. Test scores took off toward the sky. State officials noticed and provided matching money for other improvements. Luis won a promotion.

The meaning of education was revolutionized in that one village. I saw it, before and after. An old gringo named Edd and a highly motivated 19-year-old named Luis made it happen.

From education reality, back to mere supposition: It appears much of rural Mexico needs a similar miracle.