Poets have always intrigued me. Sensitive and observant about the world around them, they are an eclectic blend of artist, philosopher and dreamer and are too often underappreciated during their lifetimes.

Several years ago, I was rummaging through a box of family photos with my dad, when he showed me an old, yellowing image of his mother from 1908. He told me it was taken in Mexico at the wedding of her cousin, the poet and playwright Manuel Rocha y Chabre. It surprised me that there was a poet in our family. Since then, I’ve been on a journey to discover who he was. What I learned about him, and his kinship with my grandmother, was really quite remarkable.

Born in the city of Chihuahua in 1870, Manuel Rocha y Chabre’s maternal grandfather came to northern Mexico from Gap, a small town high up in the French Alps. His grandfather started a sugar refinery, which created jobs in the local area, and the Chabre family soon became highly regarded citizens of Chihuahua. Manuel Rocha y Chabre burst onto the literary scene in Mexico when he published his first book of poetry in 1898 titled, Cantares y Rondeles (Songs and Rondeaus). It was followed in 1898 by a three act play titled La Verganza del Soldado (The Revenge of the Soldier). But it was his collection of poems, published in 1907, that established his legacy as the city’s premier poet. Titled Flores de Ensueño or “Flowers of Fantasy,” it reflected his perspective of life, love, family and friends in Chihuahua during the city’s most prosperous era.

The decades from 1890 to 1910 represented an unparalleled period of prosperity for Chihuahua, and traces of that bygone grandeur can still be noted in its streets today. It was the city’s golden age, a virtual Renaissance and a time of abundance, the likes of which its citizens had never seen before and — arguably — have not seen since. As the city’s economy expanded, employment became plentiful. Great structures with carved stone facades like theatres, churches, government buildings and private residences were built with money earned from large family-owned businesses primarily in ranching, mining, and textile manufacturing. Money was pouring into the city, and with the economic expansion, came a greater interest and participation in the fine arts. Manuel Rocha y Chabre became, at that important point in time, a central figure in the literature of northern Mexico.

But then, the entire Renaissance collapsed in 1913, when the Mexican Revolution brought it all to an abrupt end, almost snuffing out the flame of creativity that burned so brightly for so many years. Suddenly, political leaders on both sides were being assassinated and a large number of the most influential citizens were forced to leave their homes and their homeland, seeking refuge outside Mexico. My grandmother Josefina Sini Chabre was one of those refugees, and so was her cousin Manuel Rocha y Chabre who later fled to El Paso Texas, where he lived with his wife and children until the blood stopped spilling in the streets of Chihuahua.

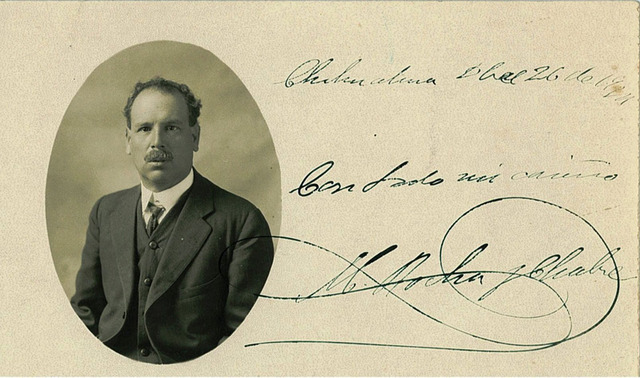

A couple of years after I found the wedding photo, my father passed away. I thought that my interest in our family’s poet would subside, but it actually intensified as I began stumbling onto more and more personal traces of this fascinating man. In a closet, I found more images of him. One was a postcard with his portrait and his noteworthy, florid signature. It was the proud, artistic signature of a man who had something to say, something important that he wanted the world to know. I discovered photos of his wife Adriana Esperon and their two children, which he had enclosed in a letter. I found a book of Spanish poetry that belonged to him, which he gave to my grandmother, and one of his published poems in a newspaper clipping from 1928 that he sent to her. As I uncovered these clues to the poet’s life, I slowly realized that he remained in touch with my grandmother until the end. And then — quite unexpectedly — I discovered my grandmother’s album. It was a small autograph book that she carried with her when she was young.

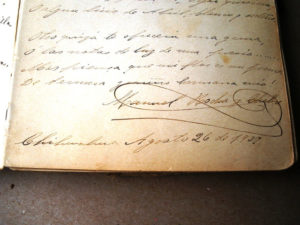

These types of signature books in which friends or relatives could inscribe a few lines were fashionable. For the ones that still survive today, they tell as much about the owner as they do about those who inscribed their thoughts in them, and Josefina’s was a very special one. It was made with high quality paper, bound in fine maroon-colored leather with gold tooling, and it had a small brass latch on it to hold the covers together. She took it everywhere asking family and friends to add a few lines to it. Apparently, it was one of the very few possessions she brought with her when she fled the revolution. As I carefully opened it for the first time, I began reading dozens of beautiful sentiments. Some were simple statements quickly scribbled, but most were very thoughtful tributes, and there were even a few pictures sketched into it by her artist friends. I was captivated, and then I came upon a poem written by her cousin, Manuel Rocha y Chabre.

He titled it “Album de Josefina” or Josephine’s Album, and in it he captured the essence of what her small book of thoughts and feelings represented. With concise wording, he painted colorful pictures while adding emotion to them with cadence and rhyme. After reading the poem in its faded ink, I wondered if he ever dedicated any of his published works to my grandmother. Great poets often write about the people they feel closest to. I thought perhaps that this question would be left unanswered, unless I could actually locate a book of his poems. As luck would have it, I was surprised to find on the Internet that his books Cantares y Rondeles and Flores de Ensueño were reprinted just this year and released for sale, so I immediately ordered a copy of each. When they arrived, I began thumbing through them until suddenly I learned the answer to my question.

Not only had he dedicated poems to the love of his life — his fiancée Adriana, but also to my grandmother Josefina and her brother Raphael, who were very important in his world as well. It was apparent that he considered my grandmother to be a muse, who inspired him to create some of his poems. Despite a difference in age of eleven years, they had a very special bond, which was more like a brother and sister than first cousins. As I read his poetry, I was very moved to learn that he even called my grandmother “hermana” or sister, and I’m sure that my grandmother must have been touched by that sentiment too.

After I read the verses in the newly reprinted paperback, I compared them with ones that I found inked onto the page of the old leather-covered book. They were the same, and it was from that poem that he selected the title for his collection of poetry Flores de Ensueño, which he wanted the world to read. At that instant, I realized that I was holding the very object, which inspired him to compose those loving words so long ago in Mexico. Manuel, the thirty seven year old writer, held that same little album in his hands on Monday August 26, 1907, when he penned those identical verses for my grandmother. I must admit, I was struck by the moment.

After the Mexican Revolution, Rocha y Chabre’s whole experience of the deaths and devastation in his homeland seemed to be too crushing for the sensitive soul that he was. Years later, after the bloody fighting stopped, he ended his exile and returned to Chihuahua a changed man. The youthful idealism, once part of his nature before the revolution, seemed to have left him and he likely felt disillusioned. Moreover, my grandmother, who provided so much inspiration for him, was now married and living far away in California. To my knowledge, he never published another book of his poetry. He died in 1934 at age 64 but, as is always the case with art, the beautiful, poetic verses that he composed when he was young can still be read and enjoyed by all of us today.

For those of you who love reading poetry, I would like to share those verses with you in Spanish and in English, with the hope that the Internet brings an even larger audience than the poet ever dreamed of reaching in 1907.

| Album de Josefina Un album es un árbol, tú lo sabes, De perrene verdor árbol querido, Donde las bellas y parleras aves Del arte y del ideal forman su nido.Donde pasan las auras vagarosas Modulando sus cánticos de amores, Donde en raudo volar las mariposas, Heridas por el sol, semejan flores.De tu album en la página primera Una flor delicada, flor de ensueño, Mi musa, para ti, dejar quisiera, — Algun lirio de abril, blanco y sedeño. Otro quizá te ofrecerá una gema | Josephine’s Album An album is a tree, you know that, A perennially green and beloved tree, Where beautiful birds chatter away Forming their nest of art and ideal.Where gentle breezes roam free Intonating their songs of love, Where in swift flutter the butterflies, Touched by the sun, resemble flowers.On the first page of this your album A delicate flower, flower of fantasy, I’d like to leave, for you, my muse, — silky white April lilies. Some other might offer you a gem |

English translation thoughtfully provided by Alejandro Bocanegro and Elise Serbaroli.

For those who are interested to read more of Manuel Rocha y Chabre’s poetry, the books Flores de Ensueño and Cantares y Rondeles can now be purchased online.

I’m working on an archival project for the New Mexico State University at Las Cruces, NM, where we scan and upload a correspondence collection that ranges from 1856-1949, and, in reading one letter, I came across a poem accredited to a Manuel Rocha y Chabre, which led me to find this post. Seeing that you are related to him, I thought I’d share what I found. This is the poem written:

“Flores Gitanas.”

Son tus flores predilectas,

Son las flores que tu amas;

Siempre misas con ternura

A sus bellas hojas blancas:

Como el alma de los niños,

Como nieve immaculada.

– Manuel Rocha y Chabre

The author of the letter quotes this poem after mentioning her beloved Daisies next to her window. Although this specific letter with this poem hasn’t been uploaded to open access just yet, there are about 2000 letters from the collection already available for anyone to access. There is a lot of correspondence from the area of Las Cruces, El Paso, and Chihuahua. It is the “Amador Family Correspondance” if interested.

Hello Raul, thanks for contacting me via MexConnect regarding the poet Manuel Rocha y Chabre. I checked the 2 books of his poetry that are referenced in my article, but the poem titled “Flores Gitanes” is not in either one. I do know that some of his poems were published in the local Chihuahua newspapers, and later in one of El Paso’s Spanish newspapers. He clipped one of those from the El Paso newspaper & sent it to my grandmother.

I also checked the letters of the Amador family that you uploaded to the Internet and saw a reference to Rocha y Chabre in a letter from December 1904. So Julieta’s friend Francisca knew of him when he was about 34 yrs old. By that time he was fairly well-known in Chihuahua, especially in artistic circles as he also had produced a couple of plays for Teatro Betancourt, the local theatre. Thank you for bringing the Amador letters to my attention, and for the important work you are doing at New Mexico State University. If you would need additional information, please don’t hesitate to contact us.

Kind regards, Joseph Serbaroli