The Valle de Maiz drops away from the old highway to Queretaro into a narrow, gloomy gulch, the dirt streets bounded by broken walls, unfinished homes, dark shadowed places and an occasional vacant lot cluttered with refuse wind blown down the canyon from the nearby Mexican mesa.

It is where the witches and sorcerers live.

They don’t call themselves that, of course, to your face. They are not brujas or brujos — they are facilitators. In fact, the ones living in San Miguel de Allende keep office hours, have cellular telephones and appointment books. And, contrary to folklore, their services are not cheap.

But then neither is the cost of living in SMA, as the local English language press is fond of calling San Miguel de Allende. Although expenses aren’t as steep as Calle Cuesta de San Jose, rising 500 vertical feet from the valley floor up Moctezuma hill, the truth is that this town has become pricey.

That very hillside twinkles at night with the halogen lamps of the wealthy Mexicans and well-to-do North Americans who call this place home—at least for part of the year.

When it is not their time to be in residence, their homes are available to rent for weeks or months at a time, complete with maid and usually a gardener. For the traveler in no hurry, a stay in such a home in such a town is the ultimate sojourn.

And San Miguel is the ultimate monument to both historical preservation and cultural wannabeeism that exists in Mexico. This is not to say that a lot of the artists and writers and musicians and dancers who live and work in SMA are not as authentic as the stuccoed walls that line its quaint, ankle-busting cobblestone streets.

But as surely as the controversy surrounding the replacement of those cobblestones with flat stones enraged the citizenry and pleased the taxi drivers, most of the residential restoration and new construction in colonial style architecture is occupied by Gringos, here because it’s the place to be. After all, San Miguel de Allende has earned a ranking within the “Top Ten Places to Live in the World” lists for over twelve years.

The opening night cocktail circuit of art galleries is a tradition among a large segment of the expatriate community. But the real artists, unless it is their work on display that night, rarely show up. They are quietly ensconced behind the massive stone or brick walls that isolate their private life from the public spectacle of town.

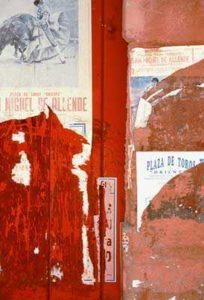

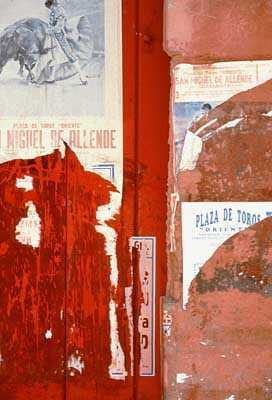

If spectacle is what sells, however, then a recent return to San Miguel by the late artist John Fulton serves to illustrate the unusual blending of life and art in this town. John was a student at the Instituto Allende in 1953, and it was then that he began a parallel career as a matador. His art also mimicked his sport, for much of his most famous work is a series of bullfight poster art.

As his fame as an artist grew, so did his reputation as a bullfighter. In a fitting end to that part of his life, and with a symmetry Hemingway would have admired, he returned to San Miguel to stage an exposition of his work at the Instituto and appear at the Plaza de Toros in the Corrida of his “Despedida,” his retirement fight.

Most of the artistic talent that resides in San Miguel, however, is much less demonstrative. Make no mistake, some of the art produced here is very good, and the atmosphere that the town and its two prestigious schools of artistic endeavor—the Bellas Artes and Instituto Allende—lend to enhance that inspiration can seize even the most inept amateur with fits of creative passion.

San Miguel is like Santa Fe, New Mexico, in that respect, as well as being its near twin historical city at the other end of the altiplano, the great North American desert. Both are at opposite ends of the Camino Real.

Founded almost five hundred years ago, SMA was home to some of Mexico’s most revered heroes, especially Ignacio Allende, one of the martyred leaders of the failed drive for independence from Spanish rule in 1810. A statue in his honor overlooks the corner of the main town square, locally called The Jardin: the garden.

A respected Mexican businessman, reflecting upon a photograph of that statue, remarked once that the pose struck in marble tended to make Allende look a little “feminine.” But, in another part of town, in the civic plaza, the hero Allende sits astride a galloping steed. The horse’s nostrils are flared, the teeth grip the bit, its hoofs are held high, and Allende, the military man, brandishes a saber in the air.

The allusion is well put, however, since San Miguel has a sizeable gay population, perhaps due to the large number of creative people drawn to its beauty and history. They seem to be involved in every civic and artistic event, and one straight resident commented that if, for some reason, the universal tolerance would disappear and force the gay community to depart, the rest of the Gringos would probably follow them out of town.

But, if no change in the social structure is desired, neither can San Miguel change architecturally from the historical colonial character that distinguishes it. El Centro, the city center, is a living, working National monument. Recent efforts to enhance that designation have included the burying of overhead power and telephone lines and the removal of all hanging business signage. In fact, all store signs must be in Spanish and painted discreetly upon the wall near the entrance to the business.

San Miguel loves to party, too. Fiestas! There are so many fiestas that at one moment in time, the Archbishop told the people to cut some out in favor of devoting more energy to working. Apparently, his dictum did not take.

And how they party.

The sounds of what locals euphemistically call fireworks rattle the windows at night, usually proclaiming the movement of some religious icon from one church to another. This town is full of religious shrines.

One particular icon is moved from a distant church to one in El Centro in the dead of night. The fireworks serve to inform the believers and wake visitors. The explosions burst like aerial bombs, their concussions awaken and frighten the dog population that either breaks into fits of howling or runs for cover. The pealing bells proclaim their painful pronouncement of yet another fiesta and the night air becomes a cantata of dogs and a cacophony of bells.

These are the times when the locals can dress up in drag, call themselves “Los Locos,” the crazies, and dance to their heart’s content. But the masks they wear must never reveal the face behind it, just as everyday life demands that the true soul be submerged to society’s standard. The crazies have just found a happier way of dealing with conformity.

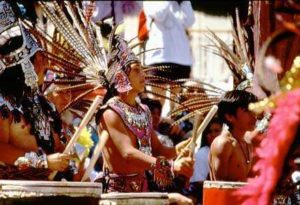

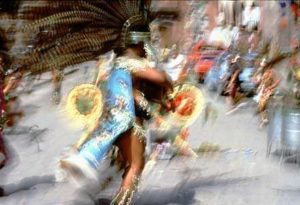

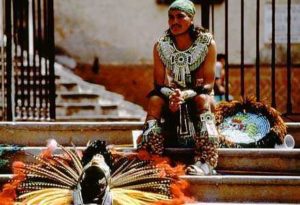

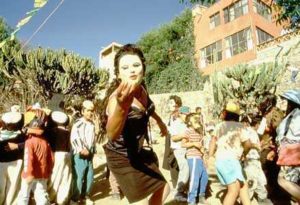

It is not uncommon to be sitting quietly in the Jardin one moment enjoying the crisp morning air, and in the next minute to be surrounded by hundreds of Indian dancers, their plumed costumes radiant in the brilliant sun.

The shifts of festival dancers continue throughout the day, while the square would be filled with whirling, chanting warriors, other dancers would lounge along the edges sipping on bottled water, awaiting their turn.

The constant pounding of the drums would be overtaken only by the massive bells of La Parroquia, the parish church and the town’s signature building. It is the very focal point of the town, probably more photographed and painted than all of the other more important churches in San Miguel.

Great flocks of pigeons call its ornately carved spires home, darting back and forth between the Jardin and the church steeples, causing the poor hapless pedestrians to duck for of fear of being hit. The town is well known for its other feathered inhabitants, as well. Until recently, sinister looking boat tailed grackles would swoop down upon the Laurel trees in the Jardin at sunset, the din of their shrieks approaching the threshold of pain. Within half an hour they had settled in for the night and the quiet returned, but woe unto the humans who passed below. The birds’ nocturnal residency in the Jardin was ended when nets were draped around the trees, forcing the night visitors out of El Centro.

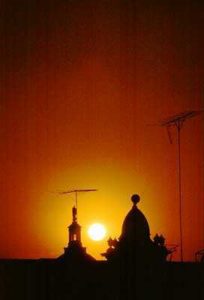

Every evening beautiful flights of white egrets and herons that nest in the tall trees of Benito Juarez park, their feathers glowing like ivory in the orange tinge of sunset, wing in formation at night fall back from the fields and lakes of the countryside.

Each day the smell of corn baking wafts from the narrow storefronts located on every street. The Tortillerias utilize a contraption in appearance not unlike farm machinery of half-a-century ago, giant Rube Goldberg devices that groan and creak as they automate handmade tortillas out of existence. A huge tin funnel consumes an enormous lump of corn flour, masa, and spits it out at the bottom onto a continuous belt as a finished tortilla. The endless procession of flat, cooked tortillas, looking like a series of silicon mother-boards with chips destined for computers, move down the conveyor belt into a basket and are eagerly snatched up by waiting customers.

House maid and Indian alike, one buying as a side dish for the employer, the other for sustenance for a family, form a line in front of each store. The native culture was founded on corn, and that simple vegetable still has a profound influence upon the daily life of Mexicans.

But now progress is invading tradition, and shelves of Bimbo white bread at the super mercado have been substituted for the Indian staff of life for the emerging Mexican middle class. White flour, much of it imported from El Norte, is finding its way into the diet and the culture.

Such a simple thing will change forever how these people live, ironically just as variations on their popular dishes have become the number one ethnic food North of the border.

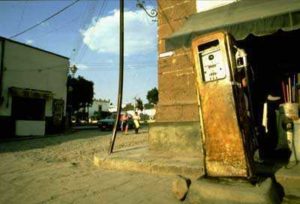

The distinctive sound of the pick-up’s horn announcing delivery of fresh milk from the farm; the melody of the small flute blown by the knife sharpener as he pushes his cart street to street; the clanging of the iron bar to warn the maids the trash man is nearby; the heaps of animal fodder small boys lug home to feed the family goats and burros—someday, perhaps, all these unique sights and sounds will disappear from San Miguel.

But if they do, will that mean an end to the inspiration that has empowered painters and artisans alike to create their treasures? Surely, the magnificent light that bathes the town will not change. The physical beauty of its buildings are a constant, too.

But the times are always changing, and no place, not even a national monument, is immune to that. When the witches start using a Day-Timer to schedule appointments to rid you of your personal demons, then it is clear that change is inescapable.