It must have been an incredibly difficult and painful journey in its time, sailing from Sevilla on the very frontier of Europe to Nueva España, then traveling on foot within the limitless boundaries of that still empty land from one end of the new empire to the other.

The 17th and 18th centuries in the New World were populated with a rugged breed of explorers, some in search of treasure and others in service to God. They were scoundrels and saints who willingly undertook that perilous passage and, in some cases, became a part of history, a still living history remaining to this day as it existed in their own time.

That fact applies as equally to the scoundrels as to the saints, but in the pursuit of the truth sometimes that very truth becomes obscured through time and revisionists—unless monuments remain to this day testifying to their human greatness or infamy.

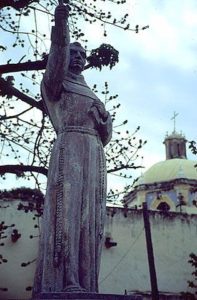

Of those early explorers who qualify as saints, the glorious monuments left behind celebrating Spanish Franciscan Fray Junipero Serra are not of him.

They are by him.

And they are found in Mexico.

They are known as the missions of the Sierra Gorda.

There are others he constructed, to be sure; the California missions are famous around the world. But the most splendid of all of Serra’s missions, the ones in Mexico, are themselves a paradox.

These particularly marvelous monuments rest among the mountains in Queretaro state, all within a few minutes drive of each other. They are the crowning jewels of the pueblos of Jalpan, Concá, Tilaco, Landa, and Tancoyol.

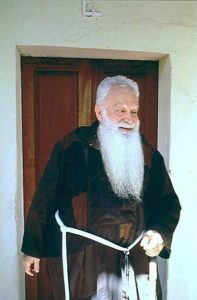

And in one of them today, a living saint, described so by his own parishioners El Santo, a Franciscan friar from Catalonia, truly named Fray Francisco Miracles, attends to his small flock alone, as he has for over thirty-three years.

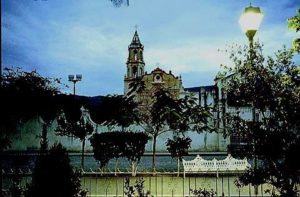

His church at Tilaco lies in a beautiful valley some ten kilometers from the state highway. The valley floor is covered with small fincas, the tilled soil of the farmlands a deep brown contrasted against the pale dried yellow of fallow pasture.

The surrounding rolling mountains are forested with a semi-tropical growth mixed with pines and cedars. A thin veil of smoke from land clearing casts a luminous haze upon the valley, softening the sunlight just as a high wispy cloud masks the sun’s brightness.

From the mirador, the lookout atop the pass into the valley, Tilaco immediately recalls the mythical Shangri-La.

Of these five missions, only Tilaco was not constructed directly by Serra, but he did supervise its overall building; saying upon seeing the finished church, “En este lugar la tierra y el cielo cantan al creador: In this place the earth and the sky sing to the creator.”

Although all the monuments by Serra are missions—sanctuaries and churches to the glory of God—it is clear that the twenty-one more famous and visited California missions, even considering the beauty of their simplicity, pale in comparison to the five missions of the Sierra Gorda.

There is nothing like the Sierra Gorda missions in the New World or the old. And within the entire New World, the spiritual contrast existing between the conquerors and their religion and the old myths and gods of the natives has never been more apparent than in the facades of these missions.

They have been described by experts as a totally original piece of work, unmatched through out the world.

And, most remarkable of all, they are still fully functional missions and have always been from their beginning, still served by the Franciscan Friars, Serra’s order. The missions have not fallen to ruin and been resurrected by a tourism department or chamber of commerce to be an attraction or museum as is the case with the California ones.

But the missions of the Sierra Gorda have been restored physically to their former glory—at least their facades have.

These are, however, working missions in the very sense of the word.

They deal with life on a daily basis today as they always have: The births, the burials, the weddings and the celebrations mutually shared by the congregation correspond closely to those performed from the time of the Spanish rule.

There is no question that the family names on the birth and death registers of these missions maintained by the good fathers have been the same, generation after generation, right down to this day almost two hundred and fifty years after the construction of these monuments.

The most obvious physical distinction between these Mexican missions and the ones that rose later in time along the California coast from San Diego to San Francisco is the use of a stone facade rather than plain stucco or plaster.

For the most part, the labor available to construct the missions of California was unskilled at the task of building the equivalent of the great stone edifices of ancient Mexico, so the good friars in California had to make do with what materials and abilities existed.

The mission in Carmel has a wonderful campanario, bell tower, but when Serra finished construction of it, the bells that rang in celebration were in Mexico City.

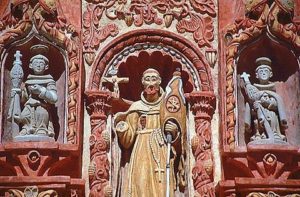

The stone faces of the Sierra Gorda missions were intricately carved by native craftsmen who had been carving stone facades for thousands of years before La Conquista. They would have the last laugh on their overseers and subjugators.

There, etched into the stone of the mission’s faces for all time, is a collection of pagan gods and symbols, political insults, creatures of the jungle and the sea, plus assorted saints, martyrs, and angels.

They are a confluent mingling of Christianity and paganism resulting in a bizarre syncretic interpretation of scriptural history. In layman’s terms, they are an astounding example of symbols reflecting spiritual order out of chaos

A chaos at least as interpreted in the minds of the Franciscans led by Junipero Serra, and the Indians they sought to convert.

Accommodations by the friars to smooth the differences, and more remarkably the similarities, of the two beliefs find their final expression in stone from bell tower top to building foundation.

The joining of two disparate worlds was never more eloquent or poignant.

The imagery in the stone seeks to glorify the saints and mythology of the Church, and yet hidden but quite visible within the carvings are symbols dealing with the ancient Indian faith.

At the top of the facade in Landa, under the feet of Saint Michael the Archangel, en Espanol Santiago Matamoros, the killer of Moors, there are representations of beheaded Moors, their tongues hanging from open mouths, so long that they drape over the parapet, a purely Indian way of showing death.

These missions are true Spanish missions, not Mexican, in the representation of saints and state-church political ties. But they are also intensely Indian in the duality of the symbolism, keeping in mind that their gods had the ability to change shape and role at will.

This may account for the ease with which Serra and the friars were able to mount the conversion of the hither-to undefeated Pames Indians. Where the Spanish army had failed, the army of the Church succeeded.

But did the Indians truly embrace the new God, or instead accept the idea that their gods had simply changed form again?

The most prominent figure on most facades is the representation of the Virgin of Guadalupe, the black Madonna, the patron saint of Mexico and the Indians. Yet, she is truly a construction of both the Church and the people to find some connection, however tenuous, in both cultures to unite them into one.

Two hundred and fifty years later, the people of the Sierra Gorda still come to the missions believing what they know in their hearts. It is a belief shared with their ancestors, who also believed in the power of the heart, so much so that ancient ritual sacrifice required the removal of the still-beating heart from the chest of the human offering.

The native religion was and is one based upon the principle of sacrifice for the appeasement of the divine power, now reduced to the less violent symbols of bread and wine, but never-the-less rooted in a common theme.

With the completion of the missions in the Sierra Gorda, a task that took Junipero Serra nine years and after another nine year period as administrator of the Apostolic College of San Fernando, he moved on to Baja California to keep up the missions originally founded by the then exiled Jesuits.

These times of exploration and the division of Western North America by the world powers of Spain, England, and Russia, ultimately led Serra to become identified as the Apostle of California.

Almost a century earlier Sir Francis Drake was the first European to discover San Francisco Bay, and he claimed the region of Northern California for England as Nova Albion in 1579.

The Spanish, fearful of both the English and a more obvious threat by Russian explorers moving South along the coast, sent the governor of Baja California, Captain Gaspar de Portola up the wild Pacific coast to establish garrisons – presidios, founded at San Diego and Monterey.

With him and the expedition of Jose de Galver in 1769 was Fray Junipero Serra, and he founded the first of the missions that would line the El Camino Real at San Diego de Alcala. In the passage of his remaining years, he founded and constructed more missions in California, being personally responsible for nine of the missions before his death.

The missions were intended to subjugate the native Indians and help supply the new forts, deemed to be too far from Mexico, with the necessary supplies for survival. Herein, however, lies the tragedy of Serra’s involvement with the California missions.

Although he has been described as dedicated to energetic discipline and zeal through constant visitations to the missions, and is credited with defending the Indians against abusive and interfering colonists, the new workers were in fact virtual slaves suffering from a high death rate due to inhuman working conditions and diseases brought by the Spanish.

At the beginning of Serra’s California projects, there were 70,000 Indian workers. By the time it had been completed, only 15,000 remained

He has also been called “enthusiastic, battling, almost quarrelsome, fearless, keen-wined, fervently devout, unselfish, and a single-minded missionary.” He died in 1784 at 71 years of age, after 34 years of missionary labor.

Over a period of 54 years beginning with San Diego twenty one missions were constructed, each one a day journey from the next.

The missions of California do share two important foot notes in Serra’s life.

Among the plants brought by Serra and his Franciscan missionaries to Alta California to help established agriculture at the new Mission San Diego were olives. Today California supplies the United States with 99% of its olive production.

The second historical oddity regards Serra’s birthplace, the tiny village of Petra on the island of Majorca, where he first served as a Friar.

Today there is a small locked chapel in the Cathedral in which Serra was both baptized, and performed baptisms later when he served the church.

Behind its doors repose statues, representations of an unlikely collection of saints that has existed since Serra’s time. They are arranged left to right, front to back to front around the room.

The names of the statues mimic the names given by Serra to the California missions South to North, beginning with the mission of San Juan Capistrano in the South, and ending in San Francisco in the North.

The legacy Serra left behind to California was the memory of his beloved home in Majorca.

The legacy left behind in Mexico remains in the form of pathos etched in stone depicting the enormous social upheaval that occurred during the death of an entire civilization and the creation of a new one.

Serra’s work survives from one end of what was Nueva España to the other, over a distance he traveled barefoot, an almost impossible task.

A task that Father Miracles of Tilaco repeated fifteen years ago.

At the age of 60, Fray Francisco Miracles walked from his mission deep in the Sierra Gorda to Alta California to witness first hand all of Serra’s other missions.

Then he walked back home again.

That was a pilgrimage of about 4,000 miles

He does not move about as easily today, his walking stick, the one that measured his step during his pilgrimage, is now a necessity. But he continues to serve the people of his parish, still trying to pursue the vision of Serra.

That vision, at times criticized because of the cultural consequences to the Native people, today remains etched in those stone facades, hidden in the valleys of the Sierra Madre Oriental Mountains of Mexico.

They are called the Five Missions of the Sierra Gorda.

They are Five Faces of God.

IF YOU GO

Junipero Serra’s Missions of the Sierra Gorda are located a four-hour-mind-inspiring-boggling ride from San Miguel De Allende, That city is recommended as a base for travel throughout the interior region of colonial Mexico, not only for its superior accommodations and tourism infrastructure, but because two of Mexico’s finest schools of continuing education are located there: The Instituto Allende, and the government-sponsored Belles Artes.

Travellers can easily arrange persona! accommodations in the Sierra Gorda and travel to the Missions if they wish to visit independently, but may lack the historical information due to a total lack of printed material in English on the Missions. There is bus service from Queretaro to Jalpan, the center of the Mission region.

TO GET THERE:

If you choose San Miguel as your base, it is located in the high desert, the Altiplano at over six thousand feet altitude 75 miles Northwest of Mexico City, a world and centuries away from the megalopolis that is Mexico’s capital. If you enter the country through Mexico City’s International airport, find the Metro terminal at the airport, buy a ticket on the Cinco or Yellow Line of the train, and ride to the stop at Terminal Norte bus station. There, purchase a ticket from one of the First Class bus companies that offer excellent, swift service to San Miguel. It will take about four hours by bus.If you wish to by-pass Mexico City completely, take a flight to the airport in Leon that serves the state of Guanajuato. You can either arrange in advance for a pick-up by one of the many travel services in San Miguel (an example is Viajes San Miguel on the web at www.enjoy-mexico.com), or you can take a taxi from Leon to San Miguel. Either way, the trip will cost you approximately $40 dollars per person although that can vary with travel services depending on the number of riders.

HOTELS:

For a town as small as San Miguel (approximately 50,000) it has an enormous selection of styles and sizes of accommodations to pick from, all the way from huge, hacienda style resort hotels on the edge of town, to small Posadas or inns that rent clean, quiet rooms for $10.00 a night.

Among those hotels in San Miguel that have found favor are Casa de Sierra Nevada, a high-end elegant hotel in the city; La Puertecita Boutique Hotel, located on Moctezuma Hill above town; Casa Schuck, a luxurious bed and breakfast located at Bajada de La Garita #3; Villa Santa Monica, at the edge of Parque Juarez, a beautiful pink colonial treasure; Villa Jacaranda, on the other side of the park, beautiful dining, and movies on a large screen TV four nights a week; Posada Carmina, a charming hotel recently renovated just steps from the Jardin, the center square.

If you choose to go independently to the Missions, the Queretaro state run Hoteles Mesones are located within a short distance of all the missions, and there are five total, the one at Concá a delightful ex-sugar hacienda.

RESTAURANTS:

In San Miguel the selection is as broad as the cuisine and prices offered. The favorites of the expatriate community are: Bugambilia; El Pegaso; El Campanario; El Meson de San Jose; Mama Mia; Tio Lucas; La Grotta; Rincon Espanol; Ten Ten Pie; and Ole-Ole’.

The independent traveler will find that each of the Hoteles Mesones near the Missions offer hall dining service.