An opalescent sky muted the harshness of the emerald earth as the old car struggled up the rock-filled Mexican road, leaving the breeze blown coast behind. I had begun a journey deep into the verdant mountains of Oaxaca, peaks that faded into the haze, massive blue-gray shapes filled with mystery and magic… and little else.

The tires spun, wildly flinging stones against the taxi’s metal belly. The metallic groans from the ancient car echoed across the jungle like funereal wailing. Although the rainy season had ended, the steaming humidity trapped by the decaying vegetation made the very air I breathed palpable.

In my worst nightmare, I had imagined traveling this road in a bus full of worthy souls, sliding and bouncing on bald tires mounted on springless wheels. That conjured agony made the actual passage in the car no less painful.

Then, suddenly, not a vision, but an actual enormous bus loomed ahead, approaching my battered car at a fearsome speed. Such an epiphany can lead to serious theological reflection.

What incredible timing, I reflected. It was Dia de los Muertos, the Day of the Dead.

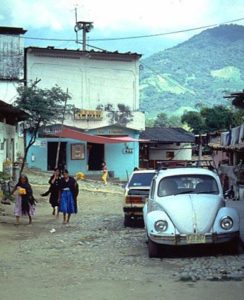

The gaudy bus, a chrome monstrosity, bore down upon the pathetic, tin metal sedan. Nameless faces pressed against the dirty, half-opened coach windows, wide-eyed in anticipation of a cataclysm. Envision yourself careening up this poor excuse for a highway in a relic of a car, destined for some ominous mountain top village to witness the Day of the Dead celebration, only to meet a bus — head on. Such madness made sense in Oaxaca, Mexico.

In our lifelong race with death, the strangest journey may be to the cemetery.

While English North Americans celebrate Halloween with costumes and candy, ancient tradition in Mexico calls for family reunions with the dead. For three days, from October 31st to November 2nd, specific rites are observed faithfully. They occur in the home and in the cemetery amid bouquets of flowers, banquets of bread, and ghostly candies ornamented with skulls.

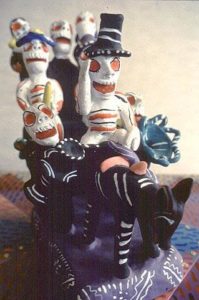

These candies are called Muertos, and are given out much the same as parents dispense candy bars and chewing gum to costumed children demanding trick or treat. But among Mexicans, the dead are considered supernatural guardians. Not only do the dead visit during this time, but they also enjoy their favorite food and drink, called “ofrendas,” lavishly laid out on home altars and shrines.

In the mountains of Oaxaca, there is a much deeper meaning to the festivity, which begins weeks, perhaps months, before the ordained days, with the collecting of the special dishes and treats which the departed spirits loved most when alive: the best chocolate for mole: fresh eggs and flour for the bread, Pan de Muerto; fruits and vegetables; even cigarettes and mescal. Lux Perpetua votive candles flame day and night, illuminating the decorative wild marigold flowers, Flor de Muertos, which adorn the altars and the graves.

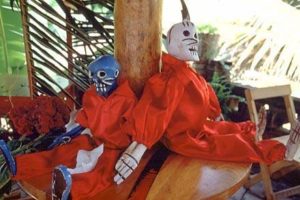

And everywhere, La Calaca, the skeleton carved from wood and dressed for a party, watches with amusement.

The passengers on the bus hurtling toward my car were rushing to visit the burial sites of departed loved ones. The distinct possibility that they might soon join the dead, in spirit as well as otherwise, accentuates the duality of belief that was being celebrated.

To the Aztecs, in order to reach the Mictlan, or region of the dead, one had to endure a perilous journey. My encounter was proving to be no exception.

Suddenly, the bus was gone, rumbling past with inches to spare, leaving a veil of dust that shrouded my sight through the cracked windshield.

My destination was Nopala, a mystical place, high in the purple mountains. I was told that of all the villages in Oaxaca, only in Nopala would I truly witness the warp and weft of centuries of tradition, with Colonial religious and ancient Indian beliefs blending into one colorful weaving.

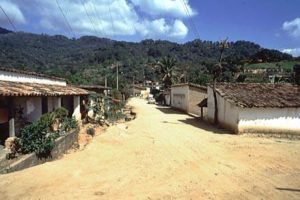

Earlier, as I was examining the wall map in the tourist office, it had seemed that state highway 131 was an all-weather, improved surface road that snaked through San Pedro and San Gabriel Mixtepec on its way to Oaxaca City. The turn-off to Nopala supposedly was in San Gabriel. Instead, there was a large vacant stretch where the village of Nopala should have been. At the outskirts of Puerto Escondido the improved surface had turned to a dusty, rock strewn road. Barely wide enough for one vehicle, it wound up the Sierra Madre del Sur Mountains to the legendary capital.

In the tiny pueblo of San Gabriel Mixtepec, a red dirt side-road set off twisting and climbing to the mountain top that is Nopala. I took the turn with the faith that the map viewed earlier was wrong, that the white space was an omission, not reality.

Soon the road reached a crystal river, and houses appeared among great groves of trees. The dirt tracks turned to cobblestones, and led me upward to the center of the village.

Finally, the pinnacle, and the mystery that is the Day of Dead became, paradoxically, alive. Carved from the rock peak, Nopala’s crowning architectural achievement is the Baroque municipal building, a glorious quasi-Colonial structure painted a brilliant white, its wrought iron balustrades crumbling from rust. Set within its plaster walls are stelae brought from the mountains hidden by clouds. The chiseled inscriptions come from ruins so far away, and from a time so remote, that few people know the story the stones tell.

The villagers of Nopala are celebrating three thousand years of history this day. They are celebrating the only thing that truly matters—the living spirit and soul of their ancestors.

A melancholy sound filled the empty square. Unearthly music played on a motley collection of discordant instruments, with only the tuba and trombone identifiable, provided a heartbeat to the ethereal pueblo. It is almost magical.

The people slowly wind their way between the leaning plaster walls to the plaza. They pass over cobblestones worn smooth by years of weather and the footfalls of generations. The women enter first from the side streets, dressed in black, yet brilliant with color. Clutched to their breasts are marigolds. Large golden blossoms are carried by everyone; some have bouquets, others only one stem.

The individual pilgrims slowly form small groups, then merge into still larger congregations until they converge as one solid processional in the stone square surrounding the crumbling church. High in the tower above the crowd, a solitary bell chimes plaintively, reverberating against the white-washed walls, rolling over the stones, tumbling down the mountain top, into the river valley below. As the music from the instruments fades, a chorus of sweet voices rises from the sanctuary, as angelic as any choir of St. Peter’s.

From the plaza’s edge, footpaths lead down and away, like the spokes of a wheel, into the jungle below. One of these leads to the cemetery.

The air is heavy with the midday heat. This is the final day, the final visit to the grave site by the family.

From the dark recesses of the church, the procession again begins its solemn sojourn. A cleric leads, the village follows.

Down the cobblestones, with the steady oompha of the tuba setting the pace, the people slowly wind their way to visit with their loved ones, to share their lives and hopes and dreams one more time.

The dead are regarded as protectors of the living, and so their counsel is sought in all family matters.

The dead demand good behavior of the living, and they have within their power the ability to reward or punish.

So death itself is merely one phase in the life-cycle, a transcendent mutation.

At the cemetery, the people quietly dispersed among the cluttered tombstones. Bright garlands of marigolds ornament the graves. A trail of their golden petals leads back the path to the village. It is strewn as a beacon, a pathway especially for the souls of los ninos, the children, the littlest angels.

The fragrance of incense mingles with the damp, musty odor of the surrounding jungle.

An ancient race that dwelt in Mexico once wrote, “We only come to dream. we only come to sleep; It is not true that we come to live on Earth.” Dia de los Muertos translates that prophecy into a mortal manifestation.

With regret I set out through the smoky haze covering the mountain back to my world. But now that world is different from the one I remember before the journey to Nopala. Now there is a continuity, a link with the living past that I hadn’t known. It is that past which is either a curse or a salvation.

And, although we all ultimately travel this adventure of life alone, there are times when you may hear La Calaca, the skeleton of death, laughing quietly behind your back.