Puros Santa Clara number among the world’s finest cigars. In fact, these fine Mexico cigars rival — and surpass — Cuban cigars in flavor and quality.

Many articles cover Mexican tobacco, hand-rolled cigars and the internationally famous owners and growers of the product. But to fully appreciate Puros Santa Clara, its owner and founder Señor Jorge Ortiz Alvarez and the other giants of the tobacco world, cigar consumers should know something of the land, Los Tuxtlas, which cultivated these men as well as their product.

I first crossed Los Tuxtlas in 1971 when it was truly isolated. Highway 185 was narrower and snaked through low-lying mountains. The world’s most northern tropical rain forest walled the highway into a corridor, hiding jungle-shrouded villages. The major road bypasses Los Tuxtlas today, so Highway 185 retains the feel of lonely seclusion. Los Tuxtlas contains a variety of climates and terrains in its roughly fifty square mile area. The tobacco growing region is more or less in the middle, and centered in and around the valley of San Andres.

Los Tuxtlas, the cradle of the mysterious Olmec civilization, is a stunningly green, rich and isolated land. With its hills and streams, the region appears as though God duplicated the Smoky Mountains and jammed them into the Gulf Coast.

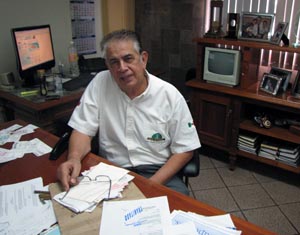

The city of San Andres, with an estimated population of 160,000, lies in the valley. Puros Santa Clara sits about midway on a three-mile stretch of bypass along a ridge above the city. A five-room fine gift shop and a large cigar rolling factory, allowing visitors to watch the process, dominates the ground floor. Señor Jorge Ortiz Alvarez had graciously granted me an interview.

Oscar, Señor Ortiz’s assistant, met me in the gift shop. I somewhat nervously followed him upstairs to talk with Señor Ortiz about tobacco and his products. An erudite, adventurous, reflective man, fluent in four languages, he probably spoke better English than I do. He welcomed me, and our conversation was fascinating. It ranged from cigars to travel to international political matters. Perhaps my parting words sum up this tobacco giant best — “Jorge, if you didn’t have a young family, I’d talk you into exploring a little known mountain region of Oaxaca with me next week.”

We passed through and by several large offices with perhaps forty busy people managing some aspect of this international business. Señor Ortiz, a tall man with a warm smile, greeted me. He sat behind a desk in a large, rectangular, well-organized room. Ten feet to his left, a lovely secretary worked away. An espresso machine occupied a space to his immediate right. Within the first moments of our conversation, it became apparent Señor Ortiz’s English was light-years ahead of my Spanish and we settled into the former for our conversation.

“I love history, so before we get to today’s cigars, I’m curious how you trace your family’s tobacco foundation to the early 1800s,” I asked, placing my notepad on the dark desk.

Señor Ortiz reflected a second. “I love history, too. Some years ago, I hired a local historian to research and write an account on tobacco growing in the region. He was to just compile a record and not to research my or any other family’s history. He found the first tobacco plants arrived in 1830. One of my forefathers was among the first growing the product here. Come with me a moment.”

We walked to large 1906 wall poster, with San Andres Tuxtla in the middle, and dozens of caption blocks giving names of local cigar companies covering the outer edges. “See, this one and that one are great uncles,” as he pointed to various boxes. “Here are relatives of Señor Alberto Turrent.”

“A fire destroyed the plant in 1984,” he said as we returned to his office. “A great deal of research and wonderful tobacco-related memorabilia was lost.”

Following his lead I sat back down. “Señor Ortiz what’s…”

“Hey, come on that’s too formal, I’m George.”

I smiled. I’d already sensed Jorge Ortiz was many things, but formal wasn’t one — unless it was required. “Thanks, George. I was going to ask; what’s your first memory of tobacco?

| Handpicking pests off plants was common on at least small farms in the United States at this same period. Until the early 1960s, a penny could buy two large butter cookies in most U.S. country stores. |

“My great-great grandfather planted 10,000 hectares or about 25,000 acres of tobacco. At that time, all Mexican tobacco was sold to Europe. My father and grandfather took time to teach me from the ground up. My first job, at age six, was picking worms off plants. We didn’t have pesticides then. They paid me ten centavos to fill a jar. Far less than an American penny, but with thirty cents I could do a good many things and attend a movie. I’m not certain I learned exactly what they wanted. I soon discovered if I only picked the big worms I could fill each bottle a great deal faster. That wasn’t really fair, skimming the plants, but I was a boy.”

I sat back in my chair, becoming more comfortable.

“Let me introduce you to my second wife and we’ll have an espresso,” George said. “You enjoy coffee, don’t you?”

The lady I’d taken as an attractive secretary wasn’t a secretary, but Mrs. Liviere de Ortiz, a competent business woman, wife and partner to George. We shook hands, and behind her shy smile I discovered a lady as gracious as George.

“I’ve always been the type guy who enjoys fine wine, coffee and chocolates, as well as cigars, and often overdo it” George said, as we prepared our espressos. “No one beats the Italians with coffee. I bought this machine so I could enjoy their espresso in Mexico. I limit myself to two cups a day for health reasons, but I tell you what, when I’m in Italy, I have to enjoy ten or twelve cups a day.”

I didn’t tell George as we savored our drinks, but I too had long loved Italian coffee and would have consumed twelve cups if he’d brewed more. “How many hectares do you farm?” I asked.

“I don’t grow any tobacco,” George set his cup down. “I founded Santa Clara Puros in 1967. My father, and back to at least my great-great-great grandfather were tobacco growers, but I wanted a different business. I didn’t have a great deal of money for the business then. I was forced to produce cigars with tobacco my father couldn’t sell internationally. I knew I had to be able to purchase tobacco from who I wanted to obtain the best tobacco. That would allow me to make the blends I wanted for a fine cigar. In 1970, I began to buy tobacco from any source that had the leaf and quality I needed. I was free to work on the quality of Santa Clara Puros.”

We were getting where I wanted to go. I’ve long thought Mexican cigars beat Cuban cigars, and this was a good time to ask about quality. “Do you have any product better than the Cuban cigar?”

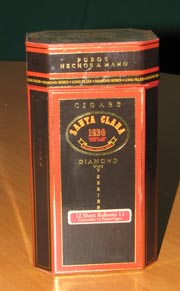

George looked surprised, but only hesitated a second. “I consider Santa Clara Diamond and Special Edition better than the Cuban product.”

I made a quick note, wondering if I could get more insight. “What’s your take on Cuban cigars at this time?”

Jorge appeared to like the subject and straightened up, “I love Cuban music and the people, but I visited East Germany twice on tobacco business. Those experiences killed any interest in visiting or further witnessing life in a totalitarian socialist society. However, I’m obviously well aware of Cuban cigars from feedback by experts, as well as personal sampling. You cannot really consider their flavor as superior, because taste is a personal preference, but the Cuban product is not aged and holds no consistency in flavor. The last box of Cuban cigars I tried had three or four different qualities in the same box — including some bitter cigars.”

Jorge thought a moment. “Cuba had the name recognition for a long time and now offers the added attraction of people buying what is forbidden. I’m not saying they’re bad cigars or have a bad flavor overall, but right now, they have an aura of taboo that helps their sales. In the long run, the blending that appeals to people will be what sells the product.”

We’d stumbled onto a subject that fascinated Jorge. “France once had that name in wine,” he said. “Everyone wanted French wine, but now dozens of regions around the world are recognized as producing as good, if not superior, grapes and wine. But in reality what and where something is grown is not always the most important aspect concerning quality, taste and flavors. Italy doesn’t grow coffee and Northern Europe doesn’t grow cacao but Italy produces the world’s best coffee and Germany, Switzerland and the Netherlands the best chocolate. They buy the best crops possible, but their superior product comes from how they blend the cacao or coffee beans. Since the cigar boom, quality has improved everywhere — except perhaps Cuba. However, like Harley Davidson motorcycles, Cuba still has the name for cigars, thanks to the taboo factor.”

I finished my last delicious sip. “Getting back to founding Santa Clara Puros and your first steps, how do you acquire tobacco?”

“We have contracts with various tobacco growers in Los Tuxtlas and several other countries. We lend them money to farm, but always reserve the right to not purchase a crop. That ensures we only go after quality. Last year the local crops weren’t good and we bought very little tobacco. This year there is a wonderful crop and we’re buying all we can obtain. This process gives me — being only a cigar producer and not grower — the flexibility to be independent of my own crop for product. It ensures I maintain a consistent quality product.”

| A mill funding farmers was a common practice in the American south into 1950s. Mills would loan farmers money for seed etc. for next growing season. |

I stretched while Liviere gave George a message.

“How many markets do you serve?”

“We’re exporting our Mexican cigars to about fifty countries. We produce about four million fine cigars a year. It’s complicated with trade restrictions on Ecuador, but I get wrapper from Ecuador and tobaccos from Nicaragua and use about seventy percent Mexican leaf from San Andres. It’s the perfect marriage and blend.”

The talk had me wanting a fine cigar, “Do you have anything new coming out?”

“This is not new, but I can say we launched Santa Clara Diamond a year and a half ago, very quietly. I have to say very quietly because the first orders consumed all our product and we remain limited with the wrapper. We’re in a good and bad situation. Santa Clara Diamond is in high demand, but it’s a struggle to catch up so we can fill orders in an expanding market. However, Santa Clara Grand Cru will launch this year. The blend is obviously a secret, but I can tell you the ingredients, not the formula. The wrapper is Nicaragua, the Jalapa area. Honduras usually has a better wrapper but this past year Nicaragua had a fantastic crop. Some of the filler also comes from Nicaragua as well as San Andres, and Piloto Cubano, from the Dominican Republic, for binding.”

“I’m lucky and know the quality of Mexican leaf,” I said, hoping I could get George to compare various tobacco regions. “But, how are the world and the United States summing up Mexican tobacco and cigars?”

George leaned back and paused a moment. “I learned long ago, buying has to be a consumer decision, but wish the public would not pass over Mexican cigars so quickly. The U.S. buyer now tends to think of Honduran and Nicaraguan tobacco and ignores almost all other tobacco producers and misses some really fine cigars. Maduro wrapper is increasing in cost and being purchased by many other countries for use in their cigars. However, when advertising; the name of Mexico is not used when other countries use our product for their blends. It’s unfortunate, but often cigar users don’t realize how much Mexican leaf is actually in Nicaraguan and other cigars.

Somehow this land known as Los Tuxtlas had kept George young. Our conversation rambled off of tobacco and into other areas. I happened to ask if he was familiar with digital cameras.

“I’m too familiar. I’m into gadgets of every type. The last time I crossed a border in Europe, the guard glanced in my backpack and said, ‘Where’s the kid?'”

“I said, ‘What?'”

“He said, ‘Laptop, iPad, digital camera, cell phone. There’s got to be a kid with you or we’ll have to put you through the full screening.'”

What started as an interview with a stranger ended speaking with a new friend. The CEO of Puros Santa Clara is a nice guy who loves analogies and uses them aptly and succinctly. At a youthful sixty-eight, he’s very proud of his family. He pays great attention to packaging and has great pride in this newer part of his business. I’d been unaware of this focus. The discovery took our conversation in an entirely new direction.

I picked my pen up. “I knew a little about your work with cedar boxes, but when did you get into the humidor side of cigars on a serious scale?”

A broad smile crossed George’s face. He reacted like he’d been waiting to get to the subject of his woodworking and humidors. The enthusiasm of a kid enjoying a new Christmas toy shined through as he delved into this new side of his business. “We’re selling humidors in fifteen countries now. We started twelve years ago. Park Lane Humidors are our new line. We’re now using lithography and covering with acrylic. This process really enhances the appearance. Since we began, the staff and workers, they’ve become experts in making high quality humidors. We use local cedar, and a lot of creativity is needed for special order humidors.”

I was catching George’s gusto, “Special order?”

George looked around a moment, but didn’t spot what he wanted, “Yes, we can’t compete with the Chinese on the prices. But we won’t compromise on quality. The quality is what sells our humidors. Among the special order humidors, we’ve built them to hold from three to 150 cigars for customers.”

About the time we really got into humidors and building techniques, George was interrupted to take a business call. Arrangements were quickly made for Oscar to show me the woodworking shop the following day. Then I went with Mrs. Liviere de Ortiz and Hayaly Bravo to study the displays. I sensed this may have been Liviere’s main end of the business, but a lot of pride and seriousness were displayed by both Mr. and Mrs. Ortiz in having the finest cigar boxes possible, as well as in the presentation of their cigars.

This was one interview I regretted ending. Beyond being interesting and insightful, Señor Jorge Ortiz Alvarez is a magnetic individual. While I looked forward to visiting the wood working facility I hoped to encounter him again without the necessity of taking notes.

All photos © William B. Kaliher, 2012