Mexico City is a center of art and culture, a required stop for world class traveling exhibits and concerts. Pop Art makes its presence known in Mexico City’s Museo de Arte de la SHCP.

Pop Art is said to be the first movement to straddle two aesthetically opposed dimensions, arriving at a fresh place where two twains were never supposed to meet. But they did meet and, in so doing, changed what art could be forever. As noted in Popism: The Warhol Sixties (Warhol & Hackett), the revolutionary aspect of Pop was a manifesto of seeing “commercial art as real art and real art as commercial art.”

No-one personified this axiom more than Andy Warhol. He began his professional career as a commercial illustrator and then proceeded to transform banal, everyday merchandise into objects of art, before turning to celebrities (who, as he said, “are also products”).

This deceptively effete pioneer muscled his way from humble beginnings in Pittsburg to become the mythical scion of The Factory, the nexus of the New York art universe. While he might be Pop Art’s most enigmatic figure, the name and the movement are synonymous: Andy Warhol is Pop Art. His rise coincided with a series of iconographic works utilizing screen printing techniques that have since become some of the most valuable “paintings” in the world. The themes hardly need reiterating, but here we go: Campbell’s soup cans, Brillo boxes, Elvis Presley, Marilyn Monroe.

Warhol’s silkscreen image “Double Elvis (Ferus Type)” sold for $37 million at Sotheby’s contemporary art sale in mid-May of 2012, while the record for a Warhol is “Green Car Crash — Burning Green Car 1,” which sold at Christie’s for $71.7 million in 2007.

There hasn’t been a breathtaking amount of interest shown in Warhol’s commercial art work, at least on a gallery level, perhaps strangely — for in the overall oeuvre of the man this seems, in retrospect, a decidedly formative period — culminating in the montage experiments with repetitive imagery through photo booth strips, line cut and photo silk screens of cars and Coke bottles that are the forerunners of the Pop movement.

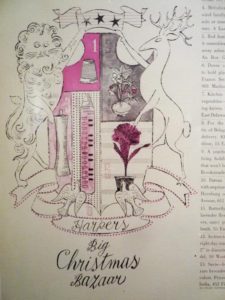

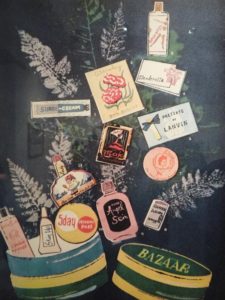

Well, that is until now, with the exhibit “Andy Warhol: The Bazaar Years (1951-1964)” — which shines a light on Warhol’s work for Harper’s Bazaar, the influential women’s magazine nurtured by its famous editor, Carmel Snow, whose goal was a publication for “well-dressed women with well-dressed minds.” Shown previously only in New York and Paris, the show’s third stop is at Mexico City‘s Museo de Arte de la SHCP, Antiguo Palacio del Arzobispado, Moneda 4, in the Centro Histórico. The exhibit features 47 works and runs until July 8 (entrance is free).

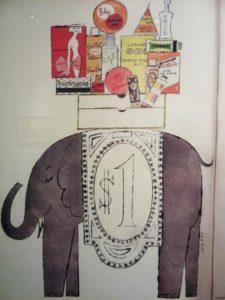

Warhol was not perhaps the world’s greatest draughtsman, yet he was considered “the perfect commercial artist” — according to influential graphic designer Milton Glaser, quoted in Pop: the Genius of Andy Warhol (Scherman & Dalton). He developed and advanced his own unique style when rendering a product as innocuous as a shoe, for instance. “Every time I draw a shoe for a job,” Warhol said, “I do an illustration for myself.”

Style is key: a Warhol image stays in your mind no matter how blasé the subject. His appealing impressions of footwear (“Leather News: Color, Color, Color”), creams, scents, handbags, lipsticks, sunglasses — even quaint illustrations for a Christmas issue — harness a color field of pure understatement, and seem to hark back to an understated, sophisticated yet ironically innocent era in American life that Warhol himself was to help detonate with an almost gleeful perversity during the cultural revolution of the 1960s.

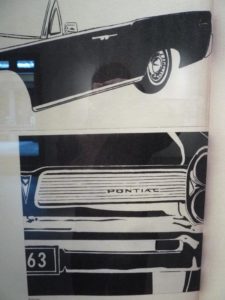

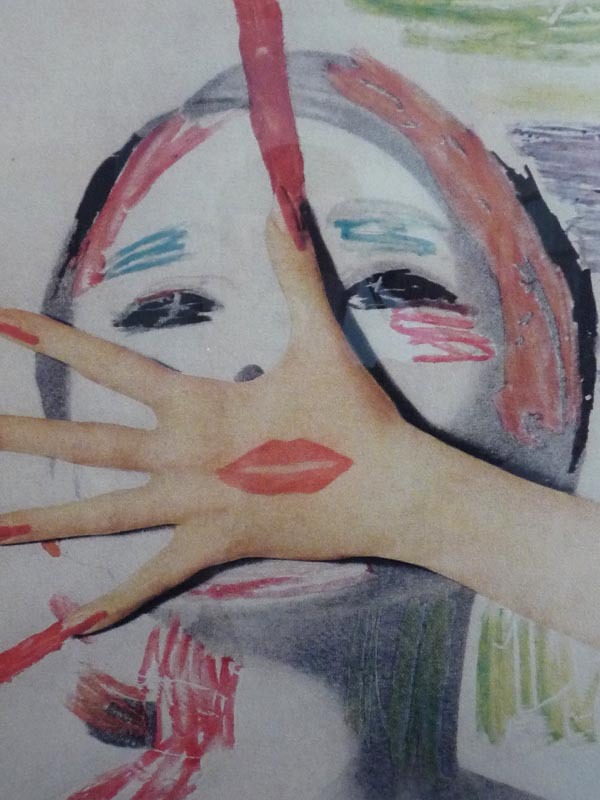

The really interesting works are positioned toward the end of the exhibit space, where the experiments that were to define Warhol’s fine art appear as unusual spreads in the pages of Harper’s. Of particular note are “Deux ex Machina” (1962) and “New Faces, New Forces” (1963). The ’62 spread concerned cars — a reflection on “the machine.” Warhol created eight canvasses — both silk screens and hand paintings — stacked against another work, 210 Coca-Cola Bottles. The effect is mesmerizing. Warhol was paid $824 for the assignment, a princely sum at the time, no doubt. The eight paintings today, not surprisingly, are worth millions.

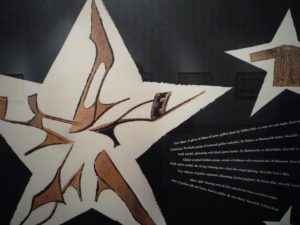

For the 1963 spread, Warhol took 14 subjects — writers, artists and playwrights whose names today no longer strike a recognizable chord (except Warhol himself) — to a Times Square Photomat, fed the machine with quarters and, with Harper’s art director Ruth Ansel helping with the layout, created a photographic montage with the results. Photo booth work was to figure predominantly in Warhol’s approach to portraiture. Both spreads embody the aesthetic we now associate with Pop.

Upon viewing “Andy Warhol, Los años Bazaar 1951-1964,” one is convinced of the merit of such an exhibition and rather mystified as to why it took so long to be organized. It is a rather brilliant display of a virtuoso in his salad days as a commercial artist, but struggling to find himself in the galleries of the fine. The inhabitants of Mexico D.F. (and visitors to the city) should consider themselves lucky to be third on the list for the tour, which is also offered free to the public.

It is interesting to note that Warhol also drew illustrations for Glamour, Life, Blue Note Records, Tiffany, and Dance Magazine throughout the aforementioned period, during which the year 1962 may be said to mark the definitive turning point from “low” to “high” art for Andy Warhol — and the art world, and the world itself. It remains to be seen if similar-themed expositions by these publications, record labels, etc. will one day follow suit.

Let’s hope they do.