The child, they said, was old enough to collect leña — kindling — from the rugged Chiapas hillsides and to mount and ride a burro. His peasant parents called him “hombrecito” — “little man” — and trusted him to care for the few chickens and goats that provided the family with sustenance.

One moonless night, awakened by the barking of dogs, he crept past his sleeping brother and sisters to investigate the commotion. How long he was gone depends upon who is telling the story but the boy returned trembling and screaming about horrible, evil things out there in the dark.

For weeks — months — he refused to leave the family’s tiny thatched hut after nightfall. Nor could he explain what the “horrible evil” was, only that it was there and he was mortally afraid of it. Finally his father, exasperated by the little hombrecito’s fear, took him out of the hut and up the hillside to prove to him that no horrible, evil things existed in the dark.

Again the stories vary. Some say there was a flash of lightning, others the howls of wolves or the leap of a jaguar. The father, startled, turned, momentarily losing his grip on the boy’s hand.

The boy vanished.

The father spent the rest of the night and the days following calling and searching but the homebrecito of the family didn’t appear.

At least not in human form.

Residents of that part of Chiapas still catch sight of his ghost. Many insist that it is important to heed his appearances because he foretells disasters and other horrible events: hurricanes, fires, contagious diseases. Or, more recently, criminal or drug dealer attacks.

Like many Mexican ghosts (of which there are hundreds) the hombrecito neither is good nor evil: He merely is.

Throughout the Western Hemisphere, pre-European inhabitants incorporated the existence of non-corporal forms into their daily lives. Ghosts, spirits and those thought to have died but who have retained earthly forms appear constantly in both Mexican folk tales and in nineteenth-, twentieth- and twenty-first-century Mexican literature. So prevalent is the belief in otherworldly contacts that, throughout Mexico, families, churches, businesses and politicians celebrate November 1 as “El Dìa de los Muertos” — the Day of the Dead.

The Evil Priest of Mexico

Frequently ghosts of persons who died violently remain on earth to guard treasures or haunt the places where they were last seen. A victim of the “Evil Priest” is one of these.

According to accounts passed orally from one generation to another several hundred years ago, this evil priest hoarded the gold coins given to his church as offerings. When one of his parishioners learned of the thefts he confronted the priest and demanded that he return the coins. The priest killed him and draped his skeleton over the buried chest in which the treasure was hidden.

On his deathbed, the priest recanted and confessed his sins, including the thefts and slaying. A caretaker overhead the confession and unearthed the chest but — as he tried to open it — a glowing ghost emerged from the skeleton. The caretaker dropped his shovel and tools and fled, so frightened by the apparition that he refused to reveal where or why he had seen it.

Some storytellers insist that other adventurers who attempted to uncover the treasure disappeared and never were heard from again.

La Llorona

Priests, good and evil, frequently appear in ghost reports. So do beautiful woman betrayed by husbands or lovers.

One of the latter, “La Llorona” (“The Weeper”), driven mad after her partner abandoned her, killed their two children and for more than two centuries has wandered the countryside seeking them. Or, according to some versions, kidnapping young children to take their places.

Baja California’s Roadside Seductress

A mysteriously beautiful woman appears beside a highway in Baja California Sur and disappears after motorists who give her a ride crash into cliffs or roll down canyons. Whether she was betrayed by a husband or lover seems not to be known.

There seems to be nothing ghostlike about her appearance — or her seductiveness — when she is offered a ride.

When questioned “What were you doing out there, beside the highway, alone?” she merely smiles and whispers, “I’ll tell you later.” But later for the driver is a disaster, not a rendezvous.

The Ghostly Nurse

The ghost of a beautiful Mexico City nurse is more benevolent.

She fell in love with a young doctor and was certain the romance that united them would last forever. But she didn’t know that the doctor was engaged to wealthy heiress.

One day he left “to attend to family business” in another part of Mexico, “business” that turned out to be his honeymoon. The news so devastated the jilted nurse that she could neither eat nor sleep and she wasted away despite all attempts to revitalize her.

She continues to haunt the hospital in which she worked and often heals patients assigned to the room in which she died.

Consuelo

Other ghosts seem merely to want companionship, like Consuelo, who died before she was able to attend her first grand ball and reappears where a young lover or husband has gone to divert himself without his partner. Only he can see her as they whirl around the dance floor together, however; to others he seems to be dancing alone.

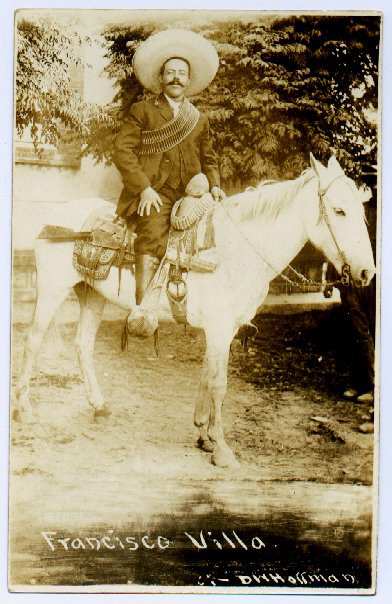

The Ghost of Pancho Villa

The ghosts of priests and deceased monks commonly protect believers and ward off evil. The ghosts of military heroes and political figures also abound, particularly during national elections. They cast hundreds of ballots, usually for incumbents, even though no one sees them vote.

The ghost of controversial revolutionary hero Pancho Villa thunders through northern Mexico waving a pistol and riding a jet black horse. For years, a myth circulated that Villa had not died and that another person’s body had been placed in his grave. He was seen in Sonoloapa, in Torreón, in San Pedro de las Colonias, in Chihuahua. Finally, it became apparent that a living man could not appear so frequently in so many places. It had to be his ghost.

Some historians believe that Villa had his head shaved and the map of his most extravagant treasure tattooed on his scalp. After his death, grave robbers decapitated his corpse to learn where this wealth was buried. The headless Villa rampages after them seeking the missing part of his anatomy.

The ghost Villa is also said to be a seducer, as is the mischievous Don Ludo, who reputedly steals young women’s maidenheads while they are sleeping. Like many otherworldly creatures he can alter his appearance and become young and handsome or appear disguised as a bird or a cat.

During his days of revolutionary banditry Villa sacked the British- and United States-owned mines of Durango and Chihuahua, emptied state treasuries and leveled the richest haciendas that existed in Mexico at that time.

When drinking or boasting about his exploits, he would throw off hints about hidden treasures: ten million in gold in Pulpito Pass concealed beneath the corpses of the ten men who helped bury the cache; even more in a cave in the Barranca de Cobre in the Sierra Madre; almost as much in Maniquipa Canyon in Chihuahua; and at least as much buried on the slopes of Mount Franklin, visible from El Paso, Texas.

Not only Villa’s ghost guards these treasures but also the ghosts of those who were murdered to keep from revealing the hiding places.

Villa’s friend Trillo Torres of Parral apparently knew of at least one of these locations. Torres told treasure seekers that the way to one of his lost fortunes was marked by the blood of the Indians that Villa hired to haul and bury the gold, then had executed. Torres refused to attempt to retrieve the treasure because the ghosts of the Indians surge from the rugged canyon in the form of vampire bats to attack those who come close to the treasure.

The Ghosts of Yucatan

Unlike Villa, the avenging spirits of the Yucatàn are not precisely ghosts but gremlin-like apparitions called aluxes (pronounced “alushes”). Several years ago while I was attending a cookout in an impoverished little town in the center of Mexico’s Yucatán peninsula, several locals told me they had seen dwarflike creatures less than a meter tall splashing in the rain or antagonizing and frightening dogs.

These aluxes are guardians of the crops and play malicious tricks on those who do not believe in them. They love sweets and insist on recompense — cakes, jellied fruit, honey — for the protection they offer. Not only that, but they can drive humans insane with their laughter and babbling.

Many Yucatecos insist that aluxes inhabited Yucatán for thousands of years before the first humans arrived; an older participant at the carne asada declared they could bring rain, start or end insect plagues and cause the earth to shake. Still another averred that they loved to play tricks but couldn’t be tricked in return because they could read a person’s intentions.

Not all Yucatecos or visitors to the state believe in their existence, however. Apparently a tourist named William Ditchbrun was one of these.

A few years ago Ditchbrun failed to return from a guided tour to the archeological site Uxmal. Three days later, hypothermic, exhausted and suffering a broken ankle, the sixty-nine-year-old Englishman told rescuers he’d been led astray by child-like voices that kept calling to him. He’d followed them into the rugged mountains, aware that they belonged to tiny figures whose presence he could sense but couldn’t see. They wouldn’t let him sleep, chattering at him in mocking voices. They threw tiny pebbles at him and when he almost had caught up with them he tripped and broke his ankle. Only then did they leave him alone.

Cemetery Ghosts

Many Mexican ghosts do not leave the places they lived or died.

So replete with ghosts is Guadalajara’s Panteón de Belén that visitors can take nightly tours through the array of monuments and tombstones to catch sight of them or feel their presence.

The ghost of Juan Soldado visits his final resting place in a cemetery in the border city of Tijuana.

Strange glowing and the sounds of laughter emanate at night from panteones in many parts of the country, particularly in Veracruz and Oaxaca.

In fact, midnight in almost any rural Mexican cemetery will make a believer out the most dubious adventurer for the emotions that the wind, the mist, earthly and unearthly noises and changes of light can bring.

“It is best to bring gifts with you,” a Oaxacan neighbor of mine advised, “otherwise…”

He left the rest to my imagination. I always take something with me when I visit a church, or graveyard, or abandoned settlement.

They could be someone’s home.