On November 20, Mexico celebrates the anniversary of the 1910 Revolution. This is a first-hand story from the memories of a Columbus judge whose grandfather died in the first battle. The Mexican Revolution continues to reverberate after 100 years.

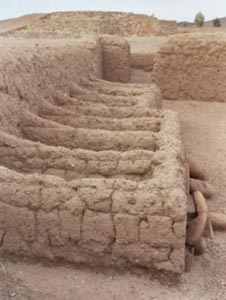

On a crisp fall evening in Casas Grandes, Chihuahua, lavender hues shimmer softly along the still-warm surfaces of earth and adobe. Deepening indigo shadows outline the Mound of the Serpent, while the towering Mound of the Heroes catches the last rays of the sun. An ancient city lies in ruins, many of its secrets still deeply buried.

The huge prehistoric adobe complex of Paquime — once home to a thriving pre-Hispanic culture of thousands — silently erodes into the giant Chihuahuan Desert. Declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1998, the ruins are within walking distance of the pueblo of Casas Grandes (“Big Houses”), located three miles from the larger town of Nuevo (New) Casas Grandes, 150 miles south of the US border at Columbus, NM.

Steeped in pre-history and history, the area has traditionally attracted archaeologists, historians, indigenous artifacts collectors and hardy souls. But accounts of increased drug cartel violence have signaled a glaring caution light to many would-be travelers.

Although high-profile, drug-related crimes have greatly escalated in the Casas Grandes area, Spencer MacCallum, an American social anthropologist who resides in the pueblo, says, “I’ve been in close contact with this area for 33 years and in that time, had there been an incident of violence against a visiting American, I would have heard of it.”

MacCallum and his wife Emalie have restored several pre-Mexican Revolution adobe buildings near the pueblo plaza. Across the street is the local funeral home, where mourners still gather outside around a smoky fire sputtering in a five-gallon can. Candles, melted during a vigil, have left jagged patches of white wax on the sidewalk. Two days earlier, a parade of family members and residents had trailed along behind yet another flower-draped casket headed down the long dusty road towards the cemetery.

“Yes, there has been violence,” MacCallum goes on, “but those at risk are not visitors. They are targeted individuals actively involved in drug trafficking.”

In the nearby plaza, where stately trees drop yellowing leaves and an ornate gazebo crowns patches of green lawn, stands a monument commemorating the March 6, 1911, Battle of Casas Grandes. The bronze plaque is simply inscribed: “May the sons of this land never forget the heroism of those who died this day.”

Since Mexican president Felipe Calderon took office in 2007 and declared war on drug traffickers, it’s estimated more than 28,000 people have died in drug-related violence. But this number pales in comparison to the million or more deaths during the Mexican Revolution, which began over a century ago in November 1910 and lasted to 1920.

Some died in battles between modern and well-equipped armies; others were killed in raids or hanged as suspects. Some died of hunger, others of sickness and disease. Sometimes foreigners were targeted and shot, their properties pillaged and plundered. Other times, villagers rose up in arms and killed in acts of popular justice. Assassinations became commonplace. Some people were kidnapped or simply disappeared. Others were quietly shoved into unmarked graves: infants, young children, women, farmers, soldiers, foreign mercenaries. The scale of killings was unprecedented.

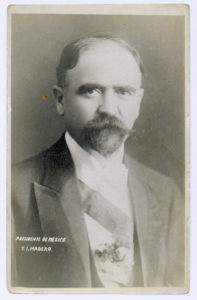

The Mexican Revolution was brought on by, among other factors, disagreement among the Mexican people over the dictatorship of President Porfirio Diaz, who had been in command for 31 years. During that time, power and wealth had been concentrated in the hands of a select few. People had no power to express opinions or select public officials, and injustices were everywhere.

Francisco I. Madero, an intellectual and idealist, was one of the strongest believers that Diaz should renounce his power and not seek re-election. Together with other young reformers, he created the “Anti-reeleccionista” party. The success of his democracy movement made Madero a threat in the eyes of Diaz. Shortly before the elections of 1910, Madero was apprehended in Monterrey and imprisoned in San Luis Potosi.

Learning of Diaz’s subsequent re-election, Madero fled to the US in October 1910. While in exile in San Antonio, Texas, he issued the “Plan of San Luis,” a manifesto that declared the elections had been a fraud and that he would not recognize Diaz as the legitimate president of the republic. Instead, Madero made the daring move of declaring himself president pro-tempore until new elections could be held.

Madero promised to return all lands that had been confiscated from the peasants, called for universal voting rights and a limit of one term for the president. His call for an uprising on November 20, 1910, marked the beginning of the Mexican Revolution.

“When the Mexican Revolution erupted in late 1910, many adventurers and soldiers of fortune traveled to Mexico to join the fight,” wrote historian John Hardman. “They came from all walks of life — professional soldier, cowboy, tradesman, businessman, doctor and newspaperman. They were rich men and poor men, thieves, murderers and cattle rustlers. Even a couple of movie stars claimed to have fought with Madero in 1911.

“They came from all over the globe — the US, France, Sweden, South Africa, Germany, Italy, Holland and Switzerland — to join the revolution, many enlisting in Madero’s El Flange De Los Estranjeros — also known as the ‘Gringo Rag-Tag Battalion.’ They came to Mexico for gold and glory — most of them receiving neither.”

Some were well known, such as Giuseppe Garibaldi, grandson of the famed Italian liberator, who served as second in command in Madero’s fledgling army. Others were shadier criminals: New Mexican John Franklin Greer, a member of the Greer Gang operating out of Bonito City in Lincoln County, had a colorful reputation as a gunslinger, train robber, gambler, soldier of fortune and ladies’ man. Both Greer and his friend John Gates joined Madero’s revolutionary forces after a train shootout and robbery in El Paso that killed local merchant C. F. Graham.

The lone battle in which Madero led his revolutionary forces against the army of President Diaz took place on March 6, 1911, at Casas Grandes. Even today, just over a hundred years later, memories of that battle remain fresh — not only in Chihuahua but here in Southwest New Mexico.

Columbus Municipal Judge Javier Lozano has lived with story of the Battle of Casas Grandes all of his life. Now 70 years old, he knows it well because his grandfather, Francisco J. Esteves, was one of Madero’s army officers killed that day.

“My grandfather was an attorney and a judge working in the mining district of Ocampo, Chihuahua, when the Mexican Revolution broke out,” Lozano recalls. “He had done work for Madero and they became friends. He represented mining concerns for the London-based Green Gold Mining Company and was highly educated on legal matters. He had also helped Madero with some of his speeches.”

Esteves, 31 years old at the time, was married to Rafaelita Polanco and father to three small children. Life had been good to the couple; they were doing well financially. Their home was nicely furnished and the children were healthy. The future looked bright. Then the massive unrest that was unleashed across Mexico changed their lives forever.

“My mother was only three years old when my grandfather left to join Madero because he was convinced revolution was a necessity,” Lozano says. “He was commissioned a lieutenant colonel in Madero’s army. My mother never saw him alive again.”

Lozano says his grandfather’s parents remained on the side of Diaz and were not happy when their son left his job and young family to join with the revolutionaries. “The family was very worried.”

He goes on, “Revolution had broken out and the revolutionaries wanted Madero to let his presence be seen in Mexico. In early February 1911, Madero was living in El Paso and still in exile.” He holds up a copy of an old photo taken six days before the Battle of Casas Grandes. Pictured along with Madero and Lozano’s grandfather are Jose Dolores Palomino, Salomon Dozal and Abraham Gonzales, governor of the state of Chihuahua.

“Madero had recruited 132 men, including my grandfather, and they crossed the Rio Grande on Feb. 13. Pancho Villa was not happy that Madero had also recruited ‘foreigners’ — Americans and Italians. Villa felt they should not be involved and interfere with Mexico’s affairs.”

Lozano says Madero had decided the revolutionaries would attack the federal military garrison at Casas Grandes, since it was a major obstacle to capturing Ciudad Juarez. “There were those of the opinion that Madero should wait until he had run in an election against Diaz, but Madero persisted. This was the first and last time Madero was ever a military commander.”

When Madero attacked Casas Grandes, he was leading an army that had swelled to several hundred infantry and cavalry. The federal garrison was commanded by Colonel Agustin A. Valdez of Mexico’s 18th battalion.

Madero and his men attacked the federal positions in Casas Grandes around 5 a.m. Fighting was still raging when, around 7:15 a.m., another Mexican federal column of 562 soldiers reinforced the already engaged 500 troops. With the reinforcing federals were two motorized vehicles, quickly put to use.

According to an account in the New York Times based on an interview with Roy Kelly, “a survivor of the American colony of fighters with Madero,” the “American Legion” commanded by Captain R. T. Harrington of El Paso made the first advance under the cover of early morning darkness. “The strength of the American Legion was maybe 60 men but could not be (accurately) stated because the Americans who have joined the revolutionary forces divided their strength instead of uniting as one body,” the article stated.

“They occupied a string of adobe houses on the main street of the town and fought from there against the machine guns and infantry stationed on the church,” the Times reported. “The machine guns were turned on them around 10 o’clock and after seven of the men… had been killed, they were forced to flee from the houses and seek shelter in the nearby woods.” Kelly reportedly saw five Americans killed while trying to escape the village through the barbed-wire fence surrounding it.

The battle lasted most of the day, with the federals and rebels repulsing each other’s counterattacks. By 5 p.m., the battle was over and Madero ordered the retreat of his forces.

The Mexican federal garrison lost 13 men and 23 were wounded. The reinforcing column lost 24 men and 37 were wounded, including their commander, Colonel Samuel G. Cuellar.

Madero, who was severely wounded in his arm, lost 85 men, among them 15 Americans. An unknown number were wounded and 41 revolutionary soldiers, including 17 Americans, were captured.

Among those in killed in Madero’s army were Lozano’s grandfather, Francisco Esteves, and two others pictured in his old photo — Jose Dolores Palomino and Salomon Dozal. Also listed among the dead were Harrington, commander of the “American Legion”; San Franciscans Robert E. Lee and Robert Evans; and Roy Glenn of Mineral Springs, Texas. In addition to the men, the revolutionaries lost 150 horses, 153 mules and 101 firearms.

A wounded Madero retreated to regroup his forces south of Casas Grandes at the sprawling Hacienda de San Diego, a grandiose estate formerly belonging to Don Luis Terrazas, a wealthy rancher who at one time owned most of the land in the state of Chihuahua. Madero blamed his scouts for the defeat at Casas Grandes. He later issued a statement saying it was the inability of the scouts to detect the reinforcing federal column that led to defeat, and he subsequently ordered all of the scouts killed.

As the battle had turned against the revolutionaries, many of Madero’s retreating forces sought shelter from the onslaught of bullets in the nearby adobe ruins of Paquime. When the gunfire smoke finally cleared, the dead were scattered all about. Villagers hurriedly picked up corpses and unceremoniously dumped them into a mass grave — the most convenient spot being a deep open shaft dug earlier by treasure-seeking looters into the side of a gigantic mound at Paquime.

Today, the site is the Mound of the Heroes, a truncated pyramid and the largest ceremonial structure within Paquime, dominating the western section of the ruins. It is a circle on all sides except the west. The exterior was originally covered with a stucco and stone façade and surrounded by a large shallow reflecting pool. Both the towering size and dominant position of the Mound of the Heroes point to its ceremonial prominence within Paquime.

Occupied from around 800 AD to between 1200 and 1450 AD, Paquime was one of the largest cities in the American Southwest and Northwest Mexico. Measuring one kilometer in diameter, it had an estimated population of around 3,000 inhabitants at its zenith.

Paquime ruins were excavated between 1958 and 1961 under the direction of Dr. Charles C. Di Peso in a cooperative effort between the Amerind Foundation of Dragoon, Ariz., and the Instituto National de Anthropologia de Historia (INAH) of Mexico. Di Peso and crews excavated approximately 42 percent of the site, recovering large quantities of shell, flaked stone, ceramics and an estimated 576 human burials.

But one site, a large mound dominating the landscape, and perhaps the most important site in the Paquime complex, remained unexcavated. Because the mound had been used as a mass burial crypt for revolutionaries killed in the Battle of Casas Grandes and due to its historic significance, DiPeso chose to leave it untouched, naming it the Mound of the Heroes.

Neither inside the adjacent museum nor outside in the ruins will visitors find an explanation for the mound’s name. And identification of those interred within its deep, dark interior remains a mystery.

“The defeat and near death of Madero had an electrifying impact on the insurrection,” wrote historian Rene De La Pedraja Toman in Wars of Latin America, 1899-1941. “When Madero entered Mexico in February 1911, the rebel leaders largely ignored him. His brush with death made the rebel leaders realize that without Madero they were little more than a brigade. Instead, under Madero, the rebel leaders belonged to the sacred cause of the ‘Revolution.’ Fully conscious that the death of Madero meant their trial and execution as common criminals, the rebel leaders rallied to his side and pledged loyalty and obedience.

“In one week Madero commanded a larger force than before the battle. His numbers more than doubled by the end of March. On April 2, Pancho Villa came with over 500 men he had recruited. The momentum Madero gained showed that the battle of Casas Grandes, rather than a defeat, had been a catalyst for spreading the insurrection.”

The revolt was a failure but it kindled revolutionary hopes in many quarters. In the north, Pascual Orozco and Pancho Villa mobilized their ragged armies and began raiding government garrisons. In the south, Emiliano Zapata raged a bloody campaign against the local rural political bosses.

In May 1911, revolutionary forces led by Pascual Orozco and Francisco Villa took Ciudad Juarez, forcing Diaz to resign. Francisco I. Madero was declared president in November.

Without Diaz as a common enemy, however, the Mexican Revolution spun quickly out of control, and Madero was deposed and executed in February 1913 igniting the most violent four years of the Revolution.

Tour buses from Tucson and Phoenix still roll into the parking lot of Paquime’s Museum of Northern Cultures. “Now they’re only arriving on weekends,” says Luis Tena, museum information clerk. “There’s still one or two but, overall, it’s más o menos, more or less. They stop here but don’t stay long. They’re all headed for Chihuahua City to see those museums.”

Near the ruins, Mayte Lujan operates Galeria de las Guacamaya, which doubles as her home and bed-and-breakfast. An astute businesswoman who constructed her buildings utilizing the same rammed-earth technique employed at Paquime, Lujan focuses on selling high-end Mata Ortiz pottery in the elite gallery. “I still get visitors,” she says, “but it’s been quieter.”

In the past, many tourists headed for the tiny village of Mata Ortiz, 16 miles south of Casas Grandes and currently home to more than 400 potters. Although influenced by ancient Paquime pottery designs, these accomplished potters have attracted international acclaim for their creative and innovative designs on handcrafted terracotta employing ancient methods. Mata Ortiz pottery is available in several Silver City galleries.

Several times a year, Tucson residents Ron and Sue Bridgemon lead “caravan” tours to Mata Ortiz. Bridgemon blames media hype for frightening Americans away from Mexican travels. “I would know if it was happening,” he says of area violence. “I see no difference now than when I started coming here 17 years ago. Look at the increased violence in Tucson. Does that keep people from going to the stores and the mall? Anywhere in the US, people are just as likely to run into crime caused by drug problems.”

Bridgemon says traffic to Mata Ortiz has dropped by half. “The potters are desperate and they’re lowering their prices. They’re calling this ‘the crises.’ One of the best-known potters was not home when we went to visit recently. I asked his wife where he was and she said he was out planting oats so he would be able to feed his horses. Other potters were out working on road-construction projects.”

Bilingual tour guide Diana Acosta says her fledgling Casas Grandes business, Agave Lindo Tours, used to be 80 percent Americans and 20 percent Mexican. “Now it’s reversed, with more Mexicans traveling within their own country,” she says. Acosta and her parents reside in a portion of the historic but crumbling Hacienda de San Diego where Madero once took refuge. Restoration work on the 1903 adobe structure “still goes on poco a poco, little by little,” she adds.

Acosta has a photo of the wounded Madero taken after the Battle of Casas Grandes. He stands in front of the hacienda’s large wooden main door, his arm and hand wrapped in white bandages. “For a short time during the revolution, this hacienda was Mexico’s White House,” she says proudly.

In the past, Las Cruces tour operator John Phelan offered three-day tours to Casas Grandes and Mata Ortiz. But those tours have been canceled and Phelan also blames the media. “People are afraid to come,” he says. “Sometimes they put money down on a trip and then get frightened when they read something in the newspaper or see it on television, so they cancel.

“Guess I’ll just sit tight and wait it out. The Paquime ruins will still be there. They’ve already been there for almost a thousand years.”

Good afternoon, I have questions of my Family (Genoevo Portillo, Enrique Portillo & Miguel Portillo } from Casas Grandes Chihuahua MX. during the Mexican Revolution that you possibly help me with…

Thank you, Michael Franco Portillo El Paso, Texas #915.996.7520 email:mdfranco99@ yahoo.com