An icon in Mexico City, the Revolution Monument or Monumento a la Revolución is also known as the Arch of the Revolution. It is located on Plaza de la Republica between downtown Reforma and Insurgentes, and has long been a premier tourist attraction, one of the capital’s architectural must-sees. Only in recent times, however, has the Monument also featured a “ride” that compares favorably with a Six Flags attraction.

The panoramic elevator running from the center of Mexico City’s Revolution Monument rises 57 meters to the access deck. © Anthony Wright, 2012

The panoramic elevator running from the center of Mexico City’s Revolution Monument rises 57 meters to the access deck. © Anthony Wright, 2012Visitors can board a sleek glass panoramic elevator that shoots up, up, up for 57 meters in a matter of seconds to arrive at an access deck inside the Monument’s stone and copper dome. If you’re of a giddy disposition, this experience is certainly not recommended! From there you negotiate a spiral staircase within the dome to the observation deck atop for some very impressive 360-degree views of the surrounding skyline.

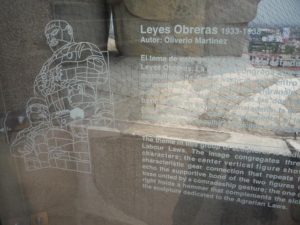

The Revolution Monument is a great place to truly breathe in the city, and also get up close and personal with Oliverio Martínez’ awesome male and female sculptures with their sickles and swords of justice representing Independence, the Reform Laws, Agrarian Laws, and Labor Laws. There is also the Adelita Café, if you’re in the mood for some light fare emphasizing Mexican cuisine. However, keep in mind that adelitas were the legendary women warriors of the Revolution — and not likely to be found in the kitchen!

Another highlight to a visit includes the Revolutionary Museum at the base of the Monument, the multimedia and exhibition space Las Crujías, plus spectacular Monument lighting that changes colors every hour from sunset till midnight. A cultural shift has seen the Monument and Republic Square play host to such diverse events as the Tecnogeist electronic music festival and the now annual gathering of thousands of local “zombies” vying to break a “Zombie Walk” Guinness Book of World Records over the Day of the Dead long weekend. Such endeavors — while obviously not everyone’s cup of tea — aim to facilitate the spirit of an evolving revolution, and the Monument’s brains trust want you to know they’re in on the party.

It’s hip to be square.

Construction on the Monument began in 1932 and took six years to complete. It was designed by architect Carlos Obregón Santacilia, who utilized Art Deco and Mexican social realism styles. It was built on the grounds of dictator Porfirio Díaz‘ grand dream for a Legislative Palace — and vanished courtesy of the Mexican Revolution, never to see the light of day (except the cupola that became part of the Monument itself).

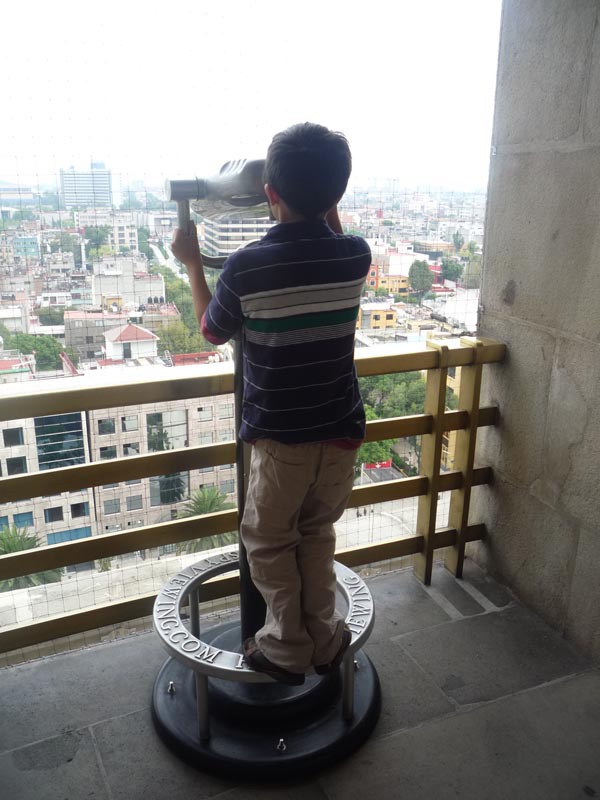

A young visitor to the Revolution Monument enjoys panoramic views of Mexico City from one of the coin-operated binoculars positioned around the observation deck © Anthony Wright, 2012

A young visitor to the Revolution Monument enjoys panoramic views of Mexico City from one of the coin-operated binoculars positioned around the observation deck © Anthony Wright, 2012Its massive columns also serve as a series of crypts forming one mausoleum — also known as the ‘Pantheon of Outstanding Men of the Revolution’ — honoring revolutionary heroes such as Venustiano Carranza (whose remains were transferred here in 1942), Francisco I. Madero (1960), Plutarco Elías Calles (1969), Lázaro Cardenas (1970), and the hard man rebel himself — Francisco ‘Pancho’ Villa (1976).

Anniversary of the Mexican Revolution

November 20 is Revolution Day in Mexico. It commemorates the anniversary of the beginning, in 1910, of a popular movement led by Francisco I. Madero that sought and achieved the overthrow of the hated dictator Díaz on the one hand. But it also kicked off the tumultuous civil war that was the Mexican Revolution, on the other. It lasted a long, tragic decade and cost, according to some estimates, up to two million lives — or one in eight Mexicans — and all but destroyed the economy.

The struggle that involved everyone from the military to liberals to rebels to landowners to peasants to the U.S. ambassador, Henry Lane Wilson, was a seemingly infinite jest of anarchic proportions — a hopeless morass of political intrigues, infighting between allies, broken alliances, executions and exiles, plunder and pillage, scorched earth policies, cries of “tierra y libertad” (“land and freedom!”) from original Zapatistas, and the deafening fusillades of firing squads.

The observation deck atop Mexico City’s Monument to the Revolution affords a splendid view © Anthony Wright, 2012

The observation deck atop Mexico City’s Monument to the Revolution affords a splendid view © Anthony Wright, 2012

Three of the illustrious men interred in the Revolution Monument — Carranza, Madero and Villa — met death at the hands of assassin’s bullets (although some say Carranza committed suicide, during an ambush in Tlaxcalantongo in the Sierra Norte de Puebla mountains in 1920). Calles was exiled, but eventually allowed to return. Only the benevolent Cardenas lived to a relatively ripe old age (75).

What were the defining results of the Revolution? The nation’s constitution was established in 1917, although sporadic fighting continued until 1920, when Álvaro Obregón became president and sought a process of national reconstruction over the following four years. (His successor, Plutarco Elías Calles, instituted a campaign against the Church that led to the bloody and brutal Cristero War from 1926-29. During this time — 1928 — Obregón was reelected president, but was assassinated by a Cristero.) In 1929, a returned Calles founded the Partido Nacional Revolucionario (National Revolution Party), renamed the Partido Revolucionario Institucional (Institutional Revolutionary Party) — or PRI — in 1946.

The PRI then basically took over Mexico for the next 71 years, and so for obvious patriotic reasons it was only fit and proper that successive PRI governments saw to it that the populace celebrated Revolution Day! The Peruvian-Spanish writer (and politician) Mario Vargas Llosa — who won the Nobel Prize in Literature — coined the term “perfect dictatorship” in 1990 to describe the PRI; on a harsher note, the Statesman Journal has stated that the PRI ran Mexico under an “autocratic, endemically corrupt, crony-ridden government.”

The original spawn of the Revolution finally lost power in 2000, but a mere 12 years later, is back and ready to rule the roost again — the people having opted to recently elect Enrique Peña Nieto as Mexico’s next PRI president.

From the observation deck of the Revolution Monument, gazing out across an imposing yet — at some compass points, shambolic — cityscape, one can almost imagine Federico Robles from Carlos Fuentes’ Where the Air is Clear somewhere down there. He has given up his idealism and is now a powerful capitalist, embedded in a system as corrupt and unequal as ever — that exalts the myths upholding it.