For some northerners, heading south of the border to live after a busy career, Mexico looks like the land of mañana. All they have to do is kick back and watch the monarch butterflies pass on their annual trek down to the state of Michoacan, while the maid whips up another batch of margaritas. This view does have its own distinct appeal.

Other expats would soon get tired of counting their fingers day after day, wondering what to do with so much time. They realize that what they need is relevance more than an extra income. They would still like to make a difference in their community, as they once did at home in Calgary or Kansas City. Fortunately, although it’s not obvious, there is a simple and elegant solution: they can join hands with those living in poverty and build houses.

Poverty is endemic in Mexico, even in my town, San Miguel de Allende, where the local economy is always flush with gringo spending.

To look at an example of this, Saul Whynman drove me out to the Ejido de Tirado, a huge tract of very poor housing, to show me the work being done by an organization called Casita Linda. He started with them a few years back as a volunteer masonry helper, after a career as a college professor and dean of adjunct faculty. Now he’s president of the organization. He didn’t mind working his way up. This ejido is a huge area encompassing five different colonias, or neighborhoods, on the edge of San Miguel. The poorest part of town, it has no city water supply or paved streets. Across a main street it faces Los Senderos, a 300-acre equestrian development with high-end residential sites, a spa, a winery and a restaurant.

“We build houses in three sizes,” Saul said, as we bumped along, “but the most common is the largest, with a footprint of four meters by eight. There’s one ahead on the left.” The numbers translate as 344 square feet on the main floor, and with the loft, the total reaches over 600.

The ejido has about two empty lots for each one with a house. Thirty-five of the fifty-four Casita Linda houses are in this area. The one we were approaching was rectangular, with an entrance in the center of the long side, and a barrel vault roof with a small skylight. This standard plan was based on work done by the Rhode Island School of Design.

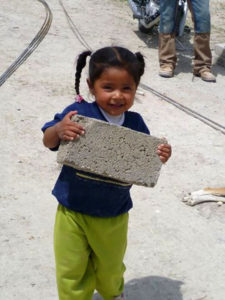

The street we drove down was so rutted that I could have walked faster. I could hardly imagine it in the rainy season. We continued to a house in progress and got out. Three or four dogs looked up as if we had disturbed their siesta. A few chickens poked around in the construction debris. Five men were laying blocks of light-weight concrete made with pumice. The door and lower-level windows were framed in and the walls were about as high as my head. They’d been working on it for five days.

Casita Linda runs two crews full time now, one of four and the other of five members. These crewmembers are all Mexican, and the organization pays them better than the local standard, so in addition to the recipients of free houses, nine families are supported just by the construction. In addition, two accountants and a social worker are employed. Offsite, another worker builds stairways and makes the steel door and window frames, as well as the doors themselves.

The largest of these houses can be built for $8,500 USD, what many American families spend on a well-deserved vacation. In the ejido, family members are encouraged to contribute with whatever skills they have.

Requirements to receive a free house are strict, but not always rigid. Children must be in school and making satisfactory grades. The father, if present, must be either employed or actively looking for a job. There can be no history of spousal abuse or alcoholism. One of the toughest ones is that the recipients have to own a piece of land with a good title. Otherwise, as tenants, they would simply be booted off by the landlord once the house was built.

I met one woman, named Ana, who has five children. They had all lived in a ragged tent. She made a living by traveling every day to the expat parts of San Miguel. There, she collected bags of garbage at each house and brought them to the sanitation truck down at the corner, earning about five pesos at each household — forty American cents. The oldest child watched the others in her absence. Her situation was obviously severe, and Casita Linda moved her to the head of the list, but it was not until an American woman in town spent $4,000 to buy a lot for Ana that they were able to build her a house. When I met her, I realized I had never seen a happier smile in my life. It was the smile of someone whose biggest and most unlikely dream had been outrun by reality.

Our last stop was a Casita Linda house that had been occupied for almost a year. Next to it was the original hovel, cobbled together from scrap lumber, corrugated metal, mud bricks loosely stacked, and cardboard. The door was a salvaged piece of advertising fabric with shredded edges, well weathered by sun and rain. The proud residents welcomed us cordially. Saul greeted them like family. They were the possessors of more status and good luck than life had ever hinted was possible. This old building was where they cooked and socialized. Why tear it down? After all, everyone knows that two structures on a property are better than one.

Saul and I walked across the narrow yard between and entered the Casita Linda house. His step was triumphant. This tiny bit of turf was a study in success. It possessed no plumbing — superfluous in an area with no city water service — but it did have electricity. Every room on both floors was a bedroom. Furnishings were beyond simple. There was no more than a mattress on the floor without linens. On all four sides, the floor was strewn with scattered clothing. There wasn’t a single stick of furniture in the house, to say nothing of a hanger or a closet.

What this house had in abundance though, was security, warmth, freedom from rain and insects, and, above all, hope. It had a sense of permanence. Advancement, if not in class or status, was still possible in meaningful ways here on this stretch of barren land. I have said in other places that there are times in Mexico when I leave my gringo eyes at home. Standing in the doorway of one such bedroom, I knew I was looking at a special kind of wealth.

Even after more than five years living in Mexico, I find it hard sometimes to know what I’m looking at, but not this time. Poverty on this scale is hard to absorb, even when you cannot mistake what it is.

Saul Whynman and I came out and said our goodbyes. I was reeling, but Saul was pumped. He knew exactly what success looked like in this context. He knew in precise detail what it took to make it happen. In his conversation, in his gestures, I could sense a building momentum. The local, state, and federal government had just given Casita Linda a grant of 640,000 pesos — $50,800. Part of it was for water catchment and storage. They had also received tax deduction status for contributions from Mexican businesses. Walls of opposition ahead were crumbling.

Mexico lacks much of the organized social safety net, both public and private, that we take for granted in the U.S. and Canada. However there is a great need for assistance, since poverty levels are higher in Mexico. Many expats give aid directly or through local organizations. Some, for example, fund their neighbor children’s education without any intermediaries. My own feeling is that it’s more possible to make an important difference here. You can see the results happen before your eyes. The beneficiaries have names and faces. The numbers count individuals rather than percentages, and often there are little or no administrative costs to eat up a chunk of your contribution.

The Casita Linda project, although a local phenomenon, is an example of the way one-on-one involvement can change the life of an entire family. Ultimately, this is how a community changes as well.

Find out more about Casita Linda’s good work at www.casitalinda.org