Despite years living in Mexico City, I had never been to the archeological zone of Templo Mayor — once the heart of the Aztec empire of Tenochtitlan, now located in the heart of the Historic Centre next to the National Palace and the Cathedral — right off the Zócalo, until very recently.

It was something of a revelation.

I cannot say if the huge crowds of mostly locals (with nary a foreign tourist in sight), are always swarming through the complex, but they certainly were on the swelteringly hot Sunday afternoon I went. It seemed as if the throng was studying every stone, column and wall with an ceremonial intensity. The handheld phones that have now replaced cameras catalogued every niche, toad altar, stone serpent and ascending ruin of the precinct. Students took notes.

This might have something to do with this year being the 25th anniversary of the opening of the Templo Mayor to the general public — which seems to serve as good enough reason for paying a visit as any. Or perhaps it is more the case that Mexicans hold a special love, or at least doubtless an undying fascination, for their amazing historical roots — for a greatness and also for a tragic fate that spellbinds virtually anyone who pauses to contemplate the annals of times past, much less the inheritors of its dramatic, almost unfathomable and surreal legacy.

The Aztec pyramids of old, the former city itself dating back to 1325 A.D., and a way of life utterly alien (yet still occasionally in evidence here and there) to our modern sensibilities, draw the imagination of scholars to pen volumes. And the allure of this world seems no different for the average Mexican — with the added attraction for the latter of a kind of race-memory thrown in, which seems to be in evidence by the expressions of silent awe one sees on the faces of the people here.

The archeological zone itself is one thing, as it invites a suspension of the current reality of life, continuing apace a mere few meters away.

The Teocalli or Templo Mayor was one of the main temple sites of the Aztecs when the city was called Tenochtitlan, and was dedicated to the gods Huitzilopochtli (god of war) and Tlaloc (god of rain). The complex was destroyed by the Spanish conquistadors in 1521. Parts of it were located again in 1978 when workers for the electric company unearthed a pre-Hispanic monolith.

Excavations began in earnest and lasted until 1982. Thirteen buildings in the area had to be demolished as a result.

The so-called Templo Mayor Project found more than 7,000 artifacts and offerings including effigies, coral, figurines, decorated skulls, gold bells, beads, ornaments, ceramic urns, silver masks, flint knives, jewelry, vessels, obsidian knives, copper rattles, ceramic sculptures of Mictlantecuhtl (the god of death), skull masks, braziers for the burning of copal — along with the remains of human sacrifice — virtually all of which are currently housed in the extraordinarily modern, state of the art Templo Mayor Museum, that in itself more than repays a visit to Templo Mayor.

This area of Tenochtitlan comprised the Sacred Precinct, the Great Pyramid, the Great Plaza, the Palace of the Eagle Warriors, the Temple of the Sun, and various temples and shrines dedicated to Quetzalcoatl and Tezcatlipoca.

At the Great Pyramid, sacrificial victims were led to the altar atop the pyramid and their hearts were ripped out by bloodthirsty priests and offered to the Aztec gods — up to a thousand a day on some occasions, when the streets ran with blood.

The Spaniards wrought total destruction on the zone after they conquered the city. A Catholic cross was placed on Templo Mayor. After the fall of Tenochtitlan in 1521, Cortés had his own city built on the site, and the Templo Mayor was buried under what is today the Historic Centre.

But the Templo Mayor deserves a visit for the museum alone, built in 1987 under the auspices of architect Pedro Ramírez Vázquez.

The museum is discreet and snug in its surroundings. You’d hardly know it is there from the Zocalo and I, for one, knew nothing of it until I came to visit Templo Mayor. This museum is categorically a wondrous experience, and for mine more than competes with its famous cousin — the Anthropology Museum opposite Chapultepec Park, which seems somewhat stale and far less imaginative in the way it presents its exhibits.

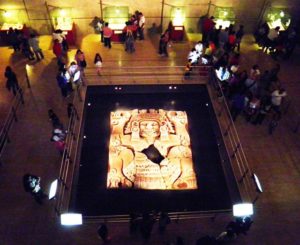

The Templo Mayor museum has four floors accessed in a compact, fluid format. Three comprise the permanent exhibitions housing the aforementioned artifacts excavated over the last 25 years (the excavating continues to this day). Earlier finds are also included, while the huge stone disk of Coyolxauhqui, dug up by the electricity workers and which kicked of the whole project, holds a prominent place here — centered like a sun from which all the other exhibits revolve around it, like cosmic spokes.

There are eight exhibition halls spread across the floors, each dedicated to a different Templo Mayor theme — such as the goddesses Coatlicue and Coyalxauhqui, mother and sister of Huitzlipochtli; to Huitzilopochtli, whose shrine at the temple was the most important; to Tlaloc; ritual and sacrifice in Tenochtitlan (including urns, funerary offerings, and objects associated with human sacrifice); the archeology and history of the site; the daily life of the people including the economy and trade of the Aztec empire; the flora and fauna of Mesoamerica prevalent during the heyday of Tenochtitlan — along with the agricultural technology of the time, such as the growing of corn and the construction of chinampas (floating gardens).

Full scale models (the likes of which are also to be seen at the Anthropology Museum), bring this era uncannily marching into the modern day — but it is especially the atmospheric lighting throughout the Templo Mayor museum that builds on the burgeoning dreamlike ambience that descends across the whole. Many visitors may feel themselves returning to a truly exotic past, and so the function of the museum to bring the past to life (as is surely the function of any museum) is stunningly realized here.