Exploring Enrique Metinides’ images is to immerse yourself in those depths of humanity awash in raw emotion, as the 79-year-old photographer has captured some of the most poignant moments to unfold on the streets of Mexico City across the span of five decades.

Much like the many accidents Metinides spent immortalizing on film throughout the course of his lauded career as a press photographer, his entrance into the profession came about purely by happenstance. “I never wanted to be a newspaper photographer,” Metinides explains. “It all came about by accident, as child’s play.”

It was Metinides’ father who set him on his career path at an early age, as he gave his son a camera and some rolls of film when the building that housed the family’s photography store was torn down in the 1940s to make way for a new construction project. Once armed with a camera, Metinides set about recording the urban reality around him. He also spent a vast amount of time escaping into the fictional gangster stories that played out on the screens at the local movie theaters, which greatly influenced the development of his photographic style. “I wanted to take photos like the movies I saw,” Metinides says, explaining that he emulated a dramatic style when shooting pictures as if he were “the cinematographer on an action film.”

During those early years of his photographic endeavors, Metinides shot images solely for his own personal collection. But a chance encounter when he was just ten years old put him on the path to becoming a published photographer whose work would go on to appear in established newspapers and magazines for decades. While snapping photos of a car accident, the young Metinides met a photographer from the Mexico City-based newspaper La Prensa, who had been assigned to shoot images of the scene. Impressed by the boy’s skill and enthusiasm, the photographer offered him the opportunity to go out and shoot together on a regular basis for the newspaper. Soon after, Metinides had his first credited photo published in La Prensa. “From there, I kept going and going and going,” Metinides recounts. “From child’s play, I went on to become a newspaper photographer.”

For decades, Metinides served as a guide of sorts, steering his newspaper audience through the hauntingly tragic moments unfolding on Mexico City’s streets and beyond. Though many of his shots appeared in Mexico’s crime press, which has long been nicknamed nota roja (red news) because of its focus on disturbingly violent images, Metinides sought to tell photographic stories soaked in cinematic drama instead of stomach-turning gore. “I took photos of another sort; not like the ones that are published today,” Metinides says. As the photographer explains, instead of just zeroing in on the bloody carnage left behind in the wake of crimes and accidents, he attempted to capture the intensity of the moment in another way, by photographing such telling details as the bullet, the weapon, the police dogs and even the pets who were left behind… like a parrot who was the only witness to a triple homicide.

This distinctive style is what has drawn many to Metinides’ work, despite the heavy subject matter of his images. “Though he covers a dark aspect of life, especially urban life, I think his way of seeing is really interesting because he sees these dramas… almost with a cinematic eye,” notes filmmaker and curator Trisha Ziff, a native of England who currently resides in Mexico City.

Ziff, who met Metinides through a fellow curator, began working with the photographer in a professional capacity six years ago. “I’m his photo family,” she says, explaining that she helps him with everything from his photo archives to his press interviews.

Soon after Ziff started working with Metinides, the two began collaborating on a project to showcase his work, which turned into the exhibition 101 Tragedies of Enrique Metinides. First shown in 2011 at the acclaimed Rencontres d’Arles photography festival in the ancient French city of Arles, the exhibition traveled to the bustling American metropolis of Manhattan at the Aperture Gallery, which is a part of the Aperture not-for-profit foundation that produces, publishes and presents photography projects both in the United States and abroad. In conjunction with the exhibition, Aperture has published a book that is also entitled 101 Tragedies of Enrique Metinides (https://www.aperture.org/shop/books/101-tragedies-of-enrique-metinides-2668?SID=), which includes images by the photographer and relevant essays about his life and work authored by Ziff.

Comprised of images carefully culled from Metinides’ archives by the photographer himself, both the exhibition and book offer viewers the opportunity to traverse Mexico during some of its darkest hours of the past five decades, witnessing everything from crimes of passion shot in stark black and white to fiery explosions captured in full color. Metinides’ narrative role is two-fold, as his photographs are accompanied by texts that give a first-person perspective of each event immortalized on film. Some accounts give a glimpse of Metinides’ own brushes with danger while covering the harrowing events that have come to define his career, such as the following story included in the exhibition: “A tanker with gas crashed into a street post and gas leaking from it ignited. Ninety people died in the explosion that followed and over a thousand people were affected. I was in another building close by taking a photograph when all this happened and it saved my life.”

These risky gambles have long been a standard part of his profession in Mexico, according to Metinides. “We risk more, get closer and even get into accidents when taking photos,” he explains, when asked what differentiates photographers in Mexico from their colleagues in the United States. “I’ve had 19 accidents while taking photos,” he adds, noting that his long list of injuries includes seven broken ribs.

Metinides traded caution for courage all throughout his career. Not only did he risk his safety on numerous occasions, but he also dared to deliver images in a unique style that veered neither towards overt censorship nor crass sensationalism of the events he covered. “Enrique did photograph things as they were, but there is actually an elegance to his images,” Ziff says. “He didn’t produce images that created in the audience this sense of having to turn away and go into a visual denial.”

“I think they are complex images and I think they really are about humanity more than violence, in a way. It is that dichotomy that I find riveting about his work,” Ziff adds. Indeed, many of the photographs Metinides has chosen to share with the public via his recent exhibition and book offer a comprehensive portrayal of tragedy, with a range of human emotions reflected on the faces of his subjects.

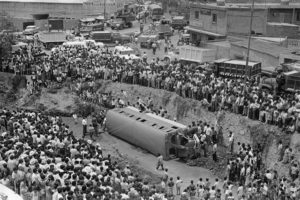

“I always tried to take photos where everything was happening in that one single image,” Metinides recalls. He excelled not only at capturing the grieving victims and grim-faced authorities at the center of many a drama, but also the concerned and often curious onlookers crowding around the fringes of these scenes. “I have seen everything… but what has always fascinated me are the people who come to watch, the onlookers (metiches, mirónes, curiosos, chismosos),” states the exhibition’s introductory text.

This theme of the onlooker is also central to the newest project involving Metinides and Ziff, a documentary to be titled El Mirón (The Onlooker), which will continue to explore the life and career of this fascinating photographer. Ziff and her film company 212berlin (https://212berlin.com/site/) are co-producing the documentary with producer Alan Suárez and his company WabiSabi Films (https://wabisabi-films.com/). Originally slated to share the same title as the book and exhibition, 101 Tragedies of Enrique Metinides, the film was renamed shortly after Ziff and Suárez returned to Mexico City from a joint trip to New York City. While in Manhattan, they attended the exhibition’s opening at the Aperture Gallery and shot footage for the documentary, whose concept has continued to evolve as filming for it continues.

“You may go in with one idea and you end up with something different,” Ziff explains. “That’s the journey of making a film.” For example, her stay in New York City involved a trip to Ground Zero, the site of the terrorist attacks that destroyed the World Trade Center in 2001. Ziff, Suárez and the rest of the crew were in search of a quintessential Metinides moment, though the travel-phobic photographer had chosen to remain behind in Mexico City. While roaming around Ground Zero, Ziff and the group chanced upon a firehouse, just as the sirens began trilling and the firetrucks began rumbling out. “It was this classic Enrique moment at Ground Zero,” the filmmaker recalls. “All of a sudden, this whole thing at Ground Zero opened up because Enrique has these albums where he collected all these images of Ground Zero,” Ziff recounts. “Did I think about that before I went to New York? No. You make room for ideas in documentary. That’s the appeal of it for me.”

These experiences prompted Ziff’s change of heart regarding the film’s title. “When I came back from New York, I said to Alan, ‘we can’t call it that (101 Tragedies of Enrique Metinides)… that’s so dark,'” the filmmaker explains. “I said we should call it El Mirón (The Onlooker) because… this is more than a film about tragedy. It’s a film about how we see. ”

Metinides himself is “the man who saw too much,” according to Ziff. She points to the photographer’s unwillingness to travel outside the country, even for his solo retrospective in New York City, as a striking example of the toll his work has taken on him. “That’s the cost of those images,” Ziff explains. “It impacts every aspect of him: his memory, his body, everything.”

Even Metinides admits that if he had to do it all over again, he would not choose to be a crime photographer. “It caused a lot of problems… so much envy and so many accidents,” he explains. “But I am satisfied with the work I accomplished.”

“I have always said that the photographer represents the reader,” Metinides muses. “When I took a photo, I knew millions of people were going to see it… so with the help of my camera, I brought readers to the scene of the action.”

Indeed, through his photography, Metinides transports his viewers to the cusp of the many dramas that have played out on Mexico City‘s streets, foisting them into the role of onlookers held rapt by the riveting scenes before them. His images, however, also offer viewers the opportunity to extend their gaze further, as any onlooker can identify with those range of emotions so visibly displayed in his work — grief, concern, despair, empathy — that breach boundaries of country, culture and creed to unite us during the most tenuous and tragic moments of life.

Much like the movies he wished to emulate, Metinides has told many stories through his images, but none so important, perhaps, as the story of what it means to be a member of the human race.

Footnote (10 May 2022): Enrique Metinides, whose photographic work was without equal, passed away on 10 May 2022, at the age of 88. QEPD.