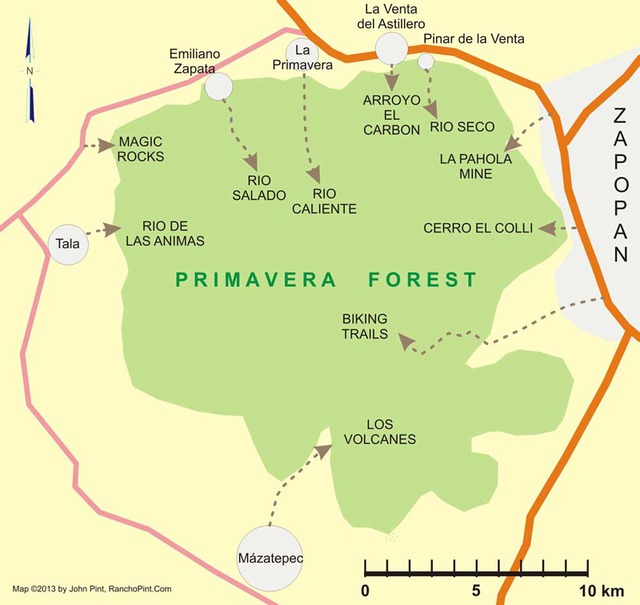

Guadalajara, Mexico’s second-largest city happens to be situated right next to a beautiful pine and oak forest covering more than 36,000 hectares (139 square miles). For as long as anyone can remember, el Bosque de la Primavera has been referred to as “Guadalajara’s lungs” and in 1980, when big-time development plans threatened the woods, the entire forest — whether publicly or privately owned — was declared a Protected Area and Wildlife Refuge.

I have been living on the edge of the Bosque for nearly 30 years and have never ceased to be amazed at how many strange and wonderful things my friends and I have discovered within its boundaries.

The purpose of this writing is to offer a brief overview of some of the forest’s sites which I have found interesting. If any arouse your curiosity, you can then follow the links to more detailed descriptions of these features.

Flora and Fauna

The forest houses around 750 species of plants and at least 225 species of animals, including around 140 kinds of birds. By day, you may come across white-tailed deer, ground squirrels, kingfishers, woodpeckers and road runners, while at night the woods come alive with raccoons, grey foxes, possums and more exotic animals like lynxes and even a few pumas.

Guides to the Primavera Forest’s animals, birds and geology are available from the park’s main office at Local E-38 in Concentro, Avenida Vallarta 6503 in Guadalajara. Their phone number is (52) 333 110-0917 / (52) 333 110-0917.

Río Caliente

The most popular entrance to the forest is through the town of La Primavera, located 12 kilometers (7.5 miles) west of Guadalajara along Highway 15 (to Nogales). A five-kilometer (3-mile) drive south brings you to the banks of the Río Caliente, the celebrated hot river, where you can enjoy a natural Jacuzzi or hike around the river’s feeder streams, some of which — like the Black River — are even hotter than “caliente.” This site is described in my book Outdoors in Western Mexico.

Several commercial balnearios (swimming pools) are also reachable via this entrance.

Pantry Gulch

Moving around the perimeter of the woods, clockwise, we come to the town of La Venta del Astillero, ten kilometers (6 miles) west of Guadalajara. If you drive straight south through La Venta, you’ll come to El Río Seco, the Dry River, featuring impressively high canyon walls marking the northern limit of the Forest.

Just a few minutes southwest of this spot is the entrance to an unforgettable slot canyon called El Arroyo del Carbón, whose walls sport curious “natural shelves.”

Gigantic Pumice Horizon

Only two kilometers (1.2 miles) to the east, at the southern end of Pinar de la Venta, the Río Seco turns south and its high, sheer walls display the geology of the Primavera Caldera, which was a lake for 10,000 years.

Here you’ll see some of the largest blocks of pumice in the world and you can then follow the arroyo to the delicious waters of Sheltered Spring or hike atop a gloriously beautiful mesa to Bluebird Belvedere, both described in Outdoors in Western Mexico.

Kaolin Mine and Arboreal Lovers

The next entrance to the forest is via Camino Arenero, a narrow cobblestone road which is located on the Nogales Highway just 2.3 kilometers (1.4 miles) west of the Periferico. Follow this three kilometers (1.9 miles) southwest to La Pahola Kaolin Mine which features 90 meters (98.4 yards) of subterranean passages with smooth, white powdery walls.

From here, you can hike up a beautiful trail for a couple of kilometers (about a mile) to Los Amantes, two intertwined trees in a picturesque meadow.

El Colli Volcanic Plug and Lookout

Now we follow the Periférico south from the Omnilife Stadium to Avenida Guadalupe. Follow this street west until you’re at the foot of Cerro El Colli.

This is a volcanic plug marking the spot where the Primavera Caldera last erupted. Hike up to the top and, among volcanic rubble and countless wildflowers (in Fall), you’ll have a great view of Guadalajara — so great I still don’t know why no one has put a restaurant here.

Biking Trails, Steam and Obsidian

A bit further south along the Ring Road we come to Mariano Otero Street, which we can follow due west to another very popular (and official) entrance to the forest. Hundreds of people regularly leave their cars in a parking area located about 9 kilometers (5.5 miles) west of the Periférico (Ring Road) and continue on into the forest from this point by bicycle or on foot.

After just 2.7 kilometers (1.7 miles), you’ll arrive at Estación Bicicleta, a groovy sort of chalet in the woods where you’ll find clean restrooms, a snack and sandwich bar, first aid for both humans and bicycles and even an art gallery! Here you can get information about dozens of trails that crisscross the woods.

Not far from the Bicycle Station, there’s a thermal area (officially off limits but much frequented by cyclists) where there are capped steam wells, hissing fumaroles and dramatic views of the Gigantic Pumice Horizon mentioned above. Further west, near the center of the forest, lies a great bed of black obsidian called El Pedernal, easily reachable by bicycle, but remember: obsidian is glass, so watch out for your tires!

Hot Pools and a Creepy-Crawly Mine

Our next access route to the forest is through the town of San Isidro Mazatepec, which is found on the Tala-Santa-Cruz highway, eighteen kilometers (11 miles) west of Tlajomulco.

Head north for seven kilometers (4.3 miles) and you’ll come to Balneario Los Volcanes where there are several warm pools fed by a small stream of hot water, which you can follow back to its source.

Only four kilometers (2.5 miles) from here lies something of a totally different nature. This is an underground obsidian mine on private property. To get into the mine, you must crawl through a small hole and creep into a large, lightless, underground room whose ceiling bristles with sharply pointed spikes of green-tinted black obsidian. Here the air is filled with vampire bats and you can see a large chunk of obsidian sticking out of the wall, almost ready for extraction. The workers, however, never finished their job, perhaps due to the sudden arrival of the Conquistadores.

Fossil Fumaroles and the River of Souls

The next entry point to the Bosque de la Primavera is through Tala, which, by the way, has a first-class museum well worth visiting.

Immediately east of Tala, there’s a failed housing development called Villa Felicidad, which is covered with bizarrely shaped rocks made of volcanic material called Tala Tuff. The strangest of all are long, vertically oriented cylinders from one to three feet in diameter, called fossil fumaroles. These were formed by streams of gas rising through pyroclastic material that fell to earth after the tremendous explosion of the Primavera Caldera, which occurred around 95,000 years ago. The paths of the rising gas eventually became harder than the surrounding material. As erosion takes place, the cylinders remain standing like tree stumps, a rhyolite forest within a forest of wood.

Two streams of clean water offer solitary swimming holes for cooling off on a hot day. One is called El Río Zarco, whose pools are freezing cold all year round and are located right in the middle of countless bizarre rock formations. The other is El Río de las Animas — the River of Ghosts — which is pleasantly cool. This picturesque river passes some of the largest fossil fumaroles and most parts of it are only reachable via trails that sometimes need clearing with a machete. Maybe it should be called the River of Adventurers.

Magic Rocks and a Cool Waterfall

If you drive 3.9 kilometers (2.5 miles) north of Tala on Highway 70, you’ll find a dirt road leading to a recreational area called Los Chorros de Tala, described in Outdoors in Western Mexico. Here you can swim beneath an impressive waterfall, picnic or camp.

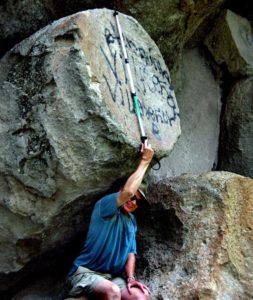

Even more attractive than the tourist facilities are the utterly bizarre rocks found just a few meters north of the dirt road leading to Los Chorros. These Magic Rocks have the shape of curving walls, sofas, bathtubs and much more, and there’s no charge at all to hike among them.

Salty River, Sweet Water, Tantalizing Trails

The last access route to the forest is through the small town of Emiliano Zapata, on Highway 70, just 8.4 kilometers (5 miles) further northeast of the Los Chorros turn. A short drive brings you to Agua Dulce, a beautiful, quiet, recreational area where a cool river is born. It’s a great place for kids to play or for camping without worries.

Just beyond lies the Salty River, deliciously warm water with hundreds of natural Jacuzzis, popularly known to kids as “The Rock-n-Roll River.” A footpath leads you on to Guava Beach (in Outdoors in Western Mexico) and an ancient obsidian workshop, while a dirt road heading south from the river leads to wonderful, solitary cycling routes through rolling hills and charming brooks, eventually leading you to Tala.

As you can see, there’s a lot more to the Primavera Forest than trees. Have fun exploring the Bosque!

I would like to make contact with John Plint concerning the fairy footstools and magic rocks in Bosque La Primavera.

I am a geologist and was the first person to describe these features in my PhD thesis in 1979.

I have forwarded your request to John Pint.

Love your stuff, John, thanks — from me, another resident of Jalisco and frequent walker in the Bosque. Also a walker in the Barranca. I sometimes wonder how legal I am in the Bosque de la Primavera but what a joy, less than an hour from my house and I rarely see anyone. Love the pine and oak forest. The saddest problem there is the trails ruined by motorbikes. Have you discovered the mountain southeast of Santa Fe Jalisco? Some day I should hire you to do a geology hike.

Thanks, Rick! We also have motos tearing up our trails near the Pinar de la Venta entrances to the Bosque. I’m told laws forbidding them “have no teeth.”

I don’t know that area near Santa Fe, but would love to go…and I can bring a real geologist along. Let’s go!